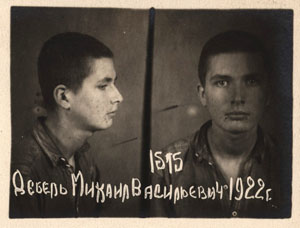

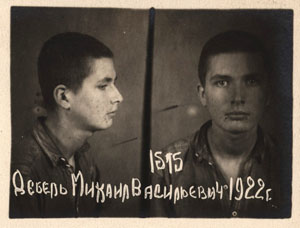

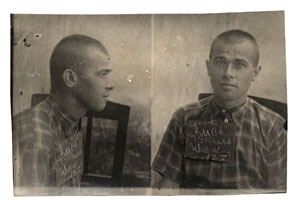

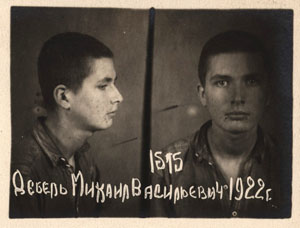

Michal Debel from Synevyr was arrested by the NKVD after fleeing to the USSR and imprisoned in Norillag for two years. He was released under an amnesty of Czechoslovak citizens in early 1943. As a Czechoslovak army soldier he fought at the Battle of Dukla Pass, where he fell between 9 and 23 September 1944.

Michal Debel from Synevyr was arrested by the NKVD after fleeing to the USSR and imprisoned in Norillag for two years. He was released under an amnesty of Czechoslovak citizens in early 1943. As a Czechoslovak army soldier he fought at the Battle of Dukla Pass, where he fell between 9 and 23 September 1944.

Michal Debel was one of roughly 6,000 refugees from Hungarian-occupied Carpathian Ruthenia who in 1939–1941 crossed the Carpathians to the part of Poland occupied by the Soviets. Most were arrested by the NKVD and sentenced to the Gulag.

Michal Debel was one of roughly 6,000 refugees from Hungarian-occupied Carpathian Ruthenia who in 1939–1941 crossed the Carpathians to the part of Poland occupied by the Soviets. Most were arrested by the NKVD and sentenced to the Gulag.

Shortly after crossing the border refugees were placed in prisons. There the detained underwent initial questioning and awaited transports further into the Soviet interior. One of them was a prison in Nadvirna which a local elementary school today uses as a store.

Shortly after crossing the border refugees were placed in prisons. There the detained underwent initial questioning and awaited transports further into the Soviet interior. One of them was a prison in Nadvirna which a local elementary school today uses as a store.

Inscriptions by prisoners can be seen in remnants of cells in the basements of the former prison in Nadvirna. Historians from the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes documented the prison in autumn 2021 in cooperation with the local branch of Memorial.

Inscriptions by prisoners can be seen in remnants of cells in the basements of the former prison in Nadvirna. Historians from the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes documented the prison in autumn 2021 in cooperation with the local branch of Memorial.

Fedir Vojčuk, born 1923, began his wanderings around the “Gulag archipelago” in Nadvirna in May 1940 and was later imprisoned in Stanislav, Kherson and Starobilsk. From there he was sent to Kolyma, where he died in an unspecified camp on 25 October 1941.

Fedir Vojčuk, born 1923, began his wanderings around the “Gulag archipelago” in Nadvirna in May 1940 and was later imprisoned in Stanislav, Kherson and Starobilsk. From there he was sent to Kolyma, where he died in an unspecified camp on 25 October 1941.

After fleeing to the USSR Anna Hresová, her husband and three-year-old son Ivan were imprisoned in Nadvirna. As with other refugees, after initial questioning they were moved to the regional prison in Stanislav (today Ivano-Frankivsk).

After fleeing to the USSR Anna Hresová, her husband and three-year-old son Ivan were imprisoned in Nadvirna. As with other refugees, after initial questioning they were moved to the regional prison in Stanislav (today Ivano-Frankivsk).

The former NKVD HQ in Ivano-Frankivsk. The rear wing contains the prison were Anna Hrysová last saw her husband and son Ivan. While in jail she gave birth to a son, Nikolaj, with whom she sentenced to three years in Karlag. In early 1943 she and her son were amnestied to Dzhambul.

The former NKVD HQ in Ivano-Frankivsk. The rear wing contains the prison were Anna Hrysová last saw her husband and son Ivan. While in jail she gave birth to a son, Nikolaj, with whom she sentenced to three years in Karlag. In early 1943 she and her son were amnestied to Dzhambul.

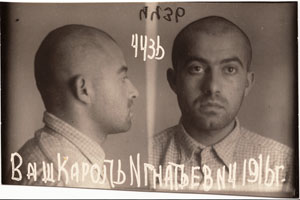

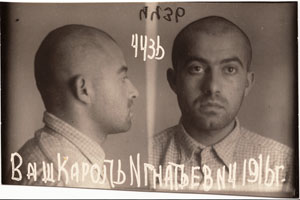

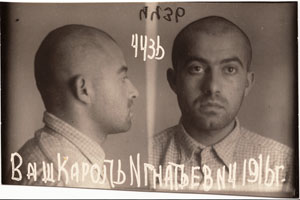

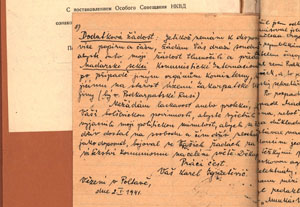

Among the prisoners who passed through prisons in Nadvirna and Ivano-Frankivsk was future notorious prosecutor Karel Vaš; he had fled to the USSR as a Communist persecuted by the Hungarian authorities.

Among the prisoners who passed through prisons in Nadvirna and Ivano-Frankivsk was future notorious prosecutor Karel Vaš; he had fled to the USSR as a Communist persecuted by the Hungarian authorities.

Karel Vaš was subsequently imprisoned in Poltava, where he sent several appeals for release to Moscow so he “could continue to fight unwaveringly for communism”. He later got three years forced labour and was sent to Intinlag.

Karel Vaš was subsequently imprisoned in Poltava, where he sent several appeals for release to Moscow so he “could continue to fight unwaveringly for communism”. He later got three years forced labour and was sent to Intinlag.

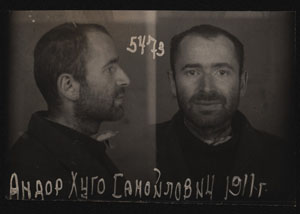

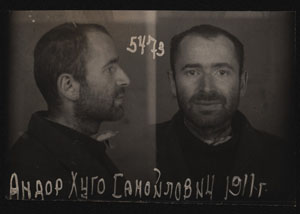

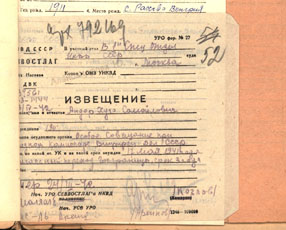

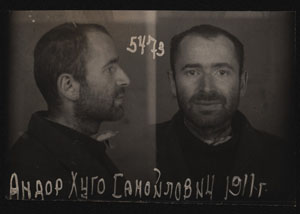

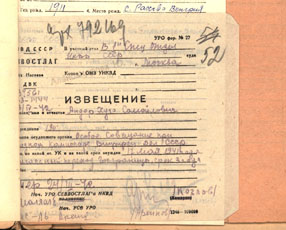

After crossing the border Hugo Andor was also imprisoned in Nadvirna. From Rachov, he had studied medicine in Prague in 1932–1938. He was sentenced to three years in the Gulag and sent to Sevvostlag in Kolyma.

After crossing the border Hugo Andor was also imprisoned in Nadvirna. From Rachov, he had studied medicine in Prague in 1932–1938. He was sentenced to three years in the Gulag and sent to Sevvostlag in Kolyma.

Hugo Andor lived to see the amnesty in the Gulag. However, two months after it was declared he died in Nagayev, today part of Magadan in Kolyma, on 24 March 1942.

Hugo Andor lived to see the amnesty in the Gulag. However, two months after it was declared he died in Nagayev, today part of Magadan in Kolyma, on 24 March 1942.

The building of the former command of the border NKVD in Skole, another border town where refugees from Carpathian Ruthenia were gathered.

The building of the former command of the border NKVD in Skole, another border town where refugees from Carpathian Ruthenia were gathered.

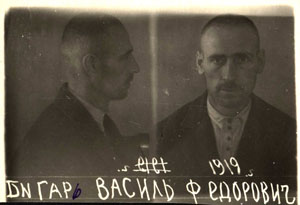

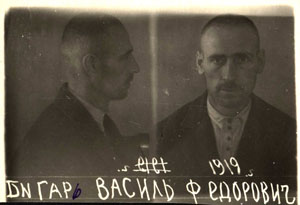

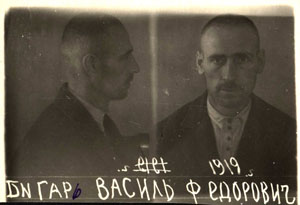

Vasil Bigar, born in Bukovec in 1919, fled as a Czechoslovak Communist Party member to the USSR, where he was instantly arrested and imprisoned in Skole. He was subsequently sentenced to three years forced labour in the Gulag in Kolyma, where he died on 7 March 1943.

Vasil Bigar, born in Bukovec in 1919, fled as a Czechoslovak Communist Party member to the USSR, where he was instantly arrested and imprisoned in Skole. He was subsequently sentenced to three years forced labour in the Gulag in Kolyma, where he died on 7 March 1943.

Refugees were sent from Skole to NKVD jails further into the interior. The first stop was the prison in nearby Stryi. Today most of the building serves as a seniors’ home. A small part has remained in its original condition.

Refugees were sent from Skole to NKVD jails further into the interior. The first stop was the prison in nearby Stryi. Today most of the building serves as a seniors’ home. A small part has remained in its original condition.

The original form of the NKVD prison in Stryi, where refugees from Czechoslovakia were imprisoned, in a period model.

The original form of the NKVD prison in Stryi, where refugees from Czechoslovakia were imprisoned, in a period model.

Also imprisoned in Stryi was Michal Karpinec, who was born in 1919 in the village of Kličanovo, where he worked on the family farm. After fleeing to the USSR he was sentenced in 1941 to three years’ forced labour at Sevvostlag in Kolyma, where he died in September 1941.

Also imprisoned in Stryi was Michal Karpinec, who was born in 1919 in the village of Kličanovo, where he worked on the family farm. After fleeing to the USSR he was sentenced in 1941 to three years’ forced labour at Sevvostlag in Kolyma, where he died in September 1941.

After several months of interrogation refugees were most often sentenced to three to five years of forced labour in the Gulag. Over half of them ended up in Komi Republic, where they worked on the construction of a railroad from Kotlas to Vorkuta and associated mining and industrial projects.

After several months of interrogation refugees were most often sentenced to three to five years of forced labour in the Gulag. Over half of them ended up in Komi Republic, where they worked on the construction of a railroad from Kotlas to Vorkuta and associated mining and industrial projects.

Gulag prisoners working on the railroad in Komi Republic.

Gulag prisoners working on the railroad in Komi Republic.

Remand prison in the 1st section of Pechorlag, one of the last remaining period landmarks of political repression in Pechora, where war refugees from Czechoslovakia were also imprisoned.

Remand prison in the 1st section of Pechorlag, one of the last remaining period landmarks of political repression in Pechora, where war refugees from Czechoslovakia were also imprisoned.

Following the Nazi attack on the USSR the Soviets changed approach, allowing the creation of a Czechoslovak military unit on their territory and the release of Czechoslovak prisoners from the Gulag. Helidor Píka, executed by the Communists after the war, played a key role in negotiations.

Following the Nazi attack on the USSR the Soviets changed approach, allowing the creation of a Czechoslovak military unit on their territory and the release of Czechoslovak prisoners from the Gulag. Helidor Píka, executed by the Communists after the war, played a key role in negotiations.

Jakub Koutný, Jan Kudlič and other Czechoslovak officers in Soviet internment in Oranky. In Buzuluk in early 1942 they will start to take in compatriots released from the Gulag and to discover the tragic extent of political repression of Czechoslovak refugees.

Jakub Koutný, Jan Kudlič and other Czechoslovak officers in Soviet internment in Oranky. In Buzuluk in early 1942 they will start to take in compatriots released from the Gulag and to discover the tragic extent of political repression of Czechoslovak refugees.

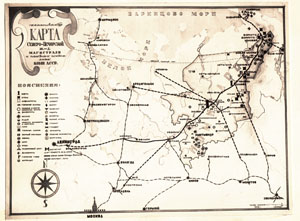

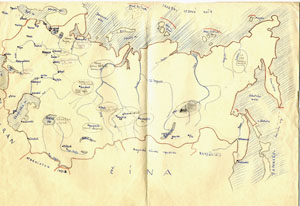

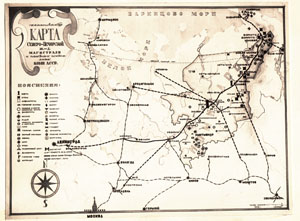

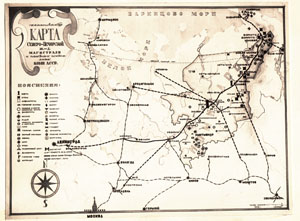

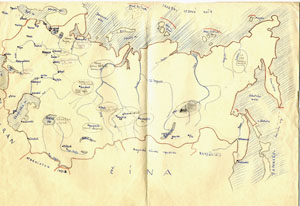

Officers released from internment attempted, on the basis of testimonies of prisoners released to Buzuluk, to document the network of camps, creating one of the first maps of the Gulag.

Officers released from internment attempted, on the basis of testimonies of prisoners released to Buzuluk, to document the network of camps, creating one of the first maps of the Gulag.

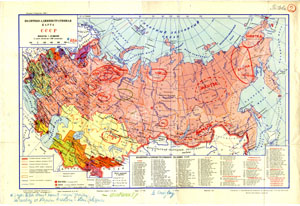

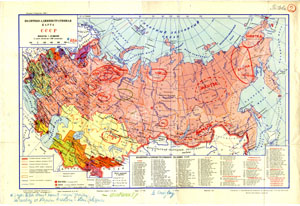

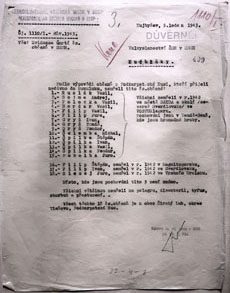

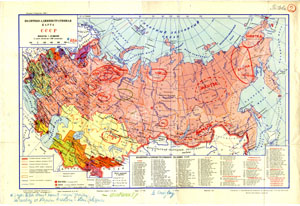

Some of the maps of the Czechoslovak military mission in the USSR include numbers of interned Czechoslovaks, who Czech officers and diplomats were striving to get released.

Some of the maps of the Czechoslovak military mission in the USSR include numbers of interned Czechoslovaks, who Czech officers and diplomats were striving to get released.

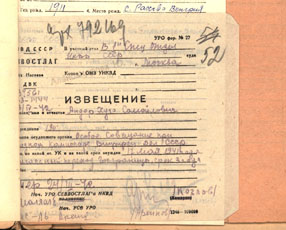

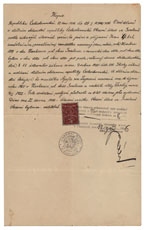

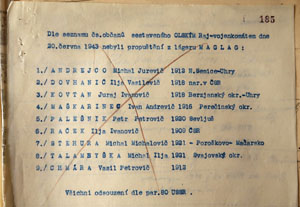

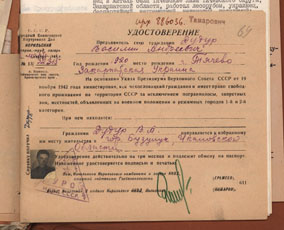

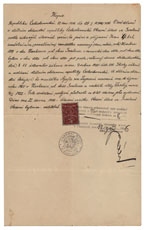

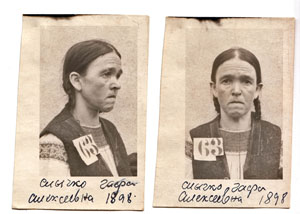

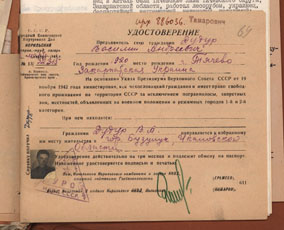

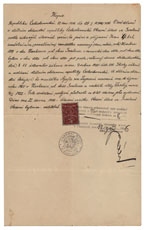

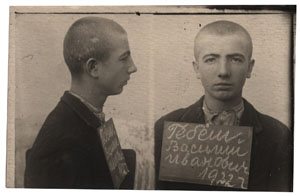

Though a great number of documents pertaining to the Czechoslovak citizenship of refugees from Carpathian Ruthenia were held in NKVD files, as was the case with student Vasil Gebeš, the Soviets were reluctant to release them. Most got out in 1943.

Though a great number of documents pertaining to the Czechoslovak citizenship of refugees from Carpathian Ruthenia were held in NKVD files, as was the case with student Vasil Gebeš, the Soviets were reluctant to release them. Most got out in 1943.

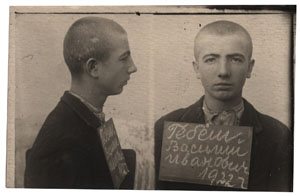

After his arrest in 1940, secondary school student Vasil Gebeš was sentenced to three years in Indevllag, from where he was released under the amnesty in early 1943. In February of that year he joined the Czechoslovak army. He fell on 13 October 1943 during an air raid on a rail transport bound for the front.

After his arrest in 1940, secondary school student Vasil Gebeš was sentenced to three years in Indevllag, from where he was released under the amnesty in early 1943. In February of that year he joined the Czechoslovak army. He fell on 13 October 1943 during an air raid on a rail transport bound for the front.

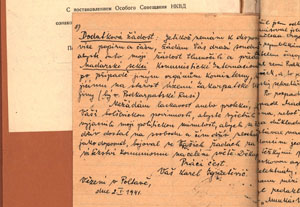

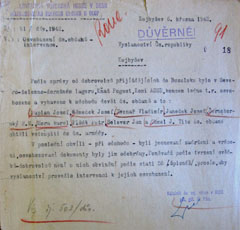

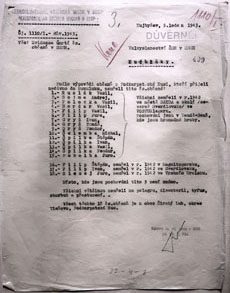

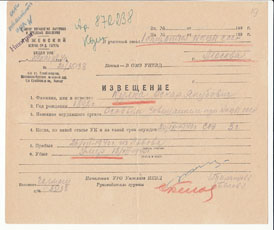

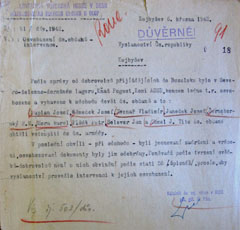

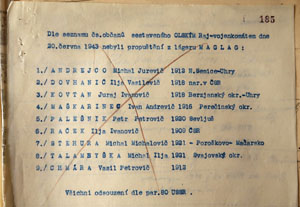

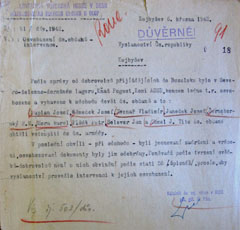

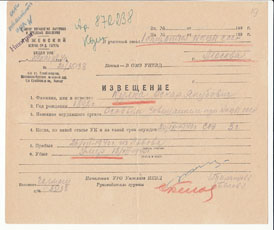

One of the reports about amnestied Czechoslovaks who were rearrested that Heliodor Píka sent to the Czechoslovak embassy.

One of the reports about amnestied Czechoslovaks who were rearrested that Heliodor Píka sent to the Czechoslovak embassy.

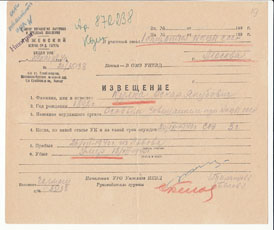

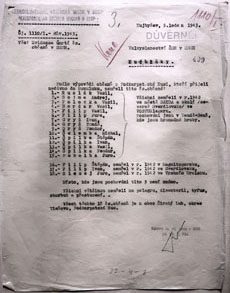

It is not yet known how many refugees died in the camps. A report by Heliodor Píka about the death of 18 Czechoslovak citizens in Gulag camps in the Urals.

It is not yet known how many refugees died in the camps. A report by Heliodor Píka about the death of 18 Czechoslovak citizens in Gulag camps in the Urals.

Some were not released at all and either died in the Gulag or got out after completing their sentences.

Some were not released at all and either died in the Gulag or got out after completing their sentences.

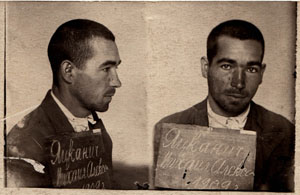

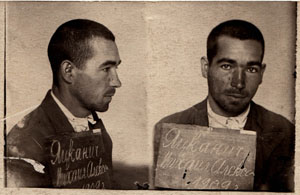

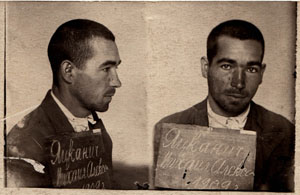

Michal Jackanič died of exhaustion and sickness on the journey from the Gulag to Buzuluk, where he hoped to join up with compatriots and enter the Czechoslovak army.

Michal Jackanič died of exhaustion and sickness on the journey from the Gulag to Buzuluk, where he hoped to join up with compatriots and enter the Czechoslovak army.

Many of those amnestied did not survive the journey from Gulag camps to the Czechoslovak army. They included Jiří Pohl, shot dead by a Soviet guard on a transport to Buzuluk.

Many of those amnestied did not survive the journey from Gulag camps to the Czechoslovak army. They included Jiří Pohl, shot dead by a Soviet guard on a transport to Buzuluk.

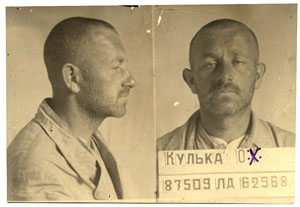

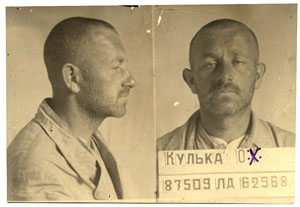

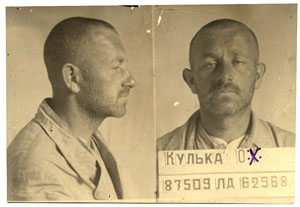

Oskar Kulka from Moravská Ostrava was arrested by the NKVD in Lviv on 9 July 1940 and imprisoned without sentence in the Karpollag camps.

Oskar Kulka from Moravská Ostrava was arrested by the NKVD in Lviv on 9 July 1940 and imprisoned without sentence in the Karpollag camps.

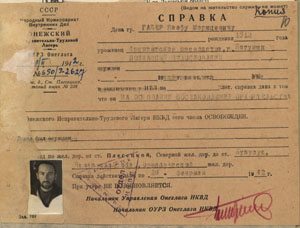

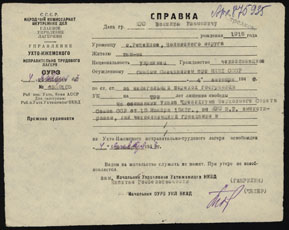

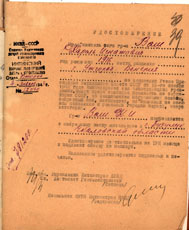

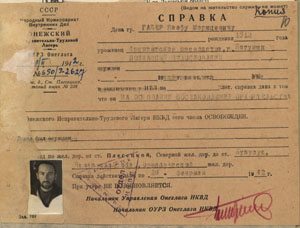

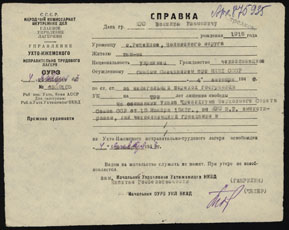

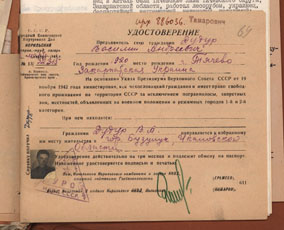

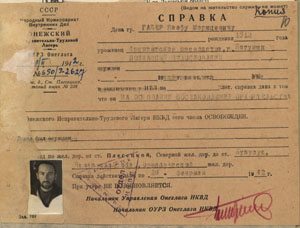

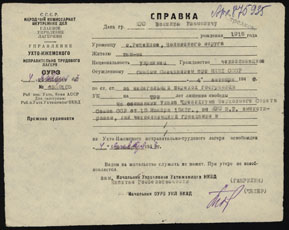

Oskar Kulka’s Gulag release papers. He was let out after the amnesty of Czechoslovak citizens on 19 January 1942. He died shortly after arriving in Buzuluk on 4 March 1942.

Oskar Kulka’s Gulag release papers. He was let out after the amnesty of Czechoslovak citizens on 19 January 1942. He died shortly after arriving in Buzuluk on 4 March 1942.

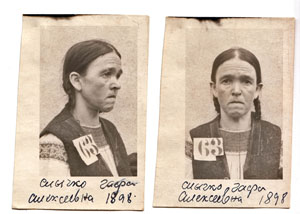

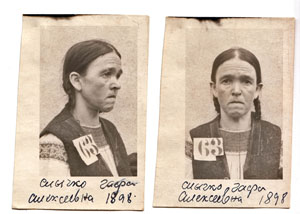

Gafa Slyčko lived to see release. She had been arrested and jailed by the NKVD after going in search of her brother, who disappeared in the USSR. Like her brother, she was amnestied as a Czechoslovak citizen to Dzhambul in 1942. However, she was only allowed go home after five years.

Gafa Slyčko lived to see release. She had been arrested and jailed by the NKVD after going in search of her brother, who disappeared in the USSR. Like her brother, she was amnestied as a Czechoslovak citizen to Dzhambul in 1942. However, she was only allowed go home after five years.

Smoke from one of the last factories from the Vorkutlag era wafts over a landscape dotted with abandoned mine shafts, former camps and prison cemeteries in which Gulag victims from Czechoslovakia also lie.

Smoke from one of the last factories from the Vorkutlag era wafts over a landscape dotted with abandoned mine shafts, former camps and prison cemeteries in which Gulag victims from Czechoslovakia also lie.

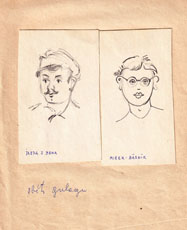

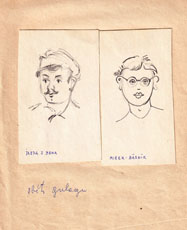

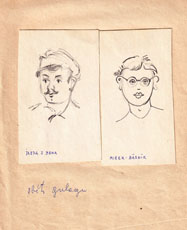

Portraits of Jaroslav Berger and Vladimír Ptáčník by Vladimír Levora, who with them fled the Nazis in the Protectorate to the USSR and was imprisoned in Vorkutlag. He was the only one to survive the hardships of the Gulag.

Portraits of Jaroslav Berger and Vladimír Ptáčník by Vladimír Levora, who with them fled the Nazis in the Protectorate to the USSR and was imprisoned in Vorkutlag. He was the only one to survive the hardships of the Gulag.

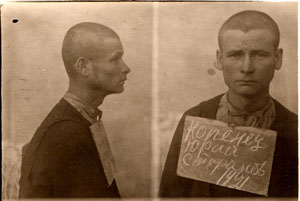

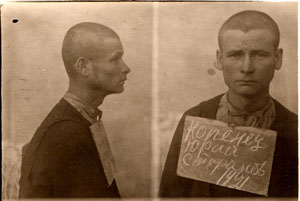

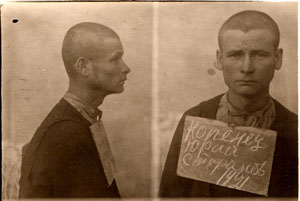

Also among the Czechoslovak prisoners in Vorkutlag was Jiří Kopinec, deployed on the construction of a bridge over the Vorkuta River. In 2008 he gave the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes an interview about his imprisonment.

Also among the Czechoslovak prisoners in Vorkutlag was Jiří Kopinec, deployed on the construction of a bridge over the Vorkuta River. In 2008 he gave the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes an interview about his imprisonment.

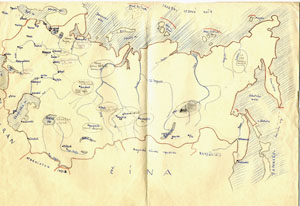

Following his return to Czechoslovakia Vladimír Levora wrote and illustrated a memoir of the Gulag. In 1958 he was sentenced to jail for so-called libel of an allied power. His memoir wasn’t published until after 1989.

Following his return to Czechoslovakia Vladimír Levora wrote and illustrated a memoir of the Gulag. In 1958 he was sentenced to jail for so-called libel of an allied power. His memoir wasn’t published until after 1989.

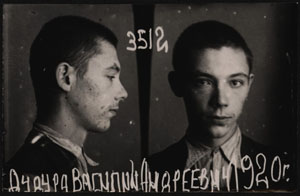

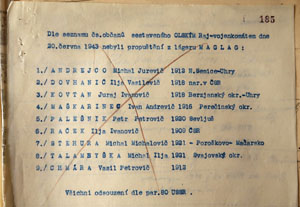

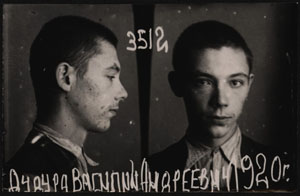

Jura Dankanič was born in Palmerton, USA in 1917. After returning to Carpathian Ruthenia he worked on the family farm. Following his escape to the USSR he was sentenced to Sevzheldorlag. After being released he fell as a Czechoslovak soldier in fighting for the Carpathians on 10 September 1994.

Jura Dankanič was born in Palmerton, USA in 1917. After returning to Carpathian Ruthenia he worked on the family farm. Following his escape to the USSR he was sentenced to Sevzheldorlag. After being released he fell as a Czechoslovak soldier in fighting for the Carpathians on 10 September 1994.

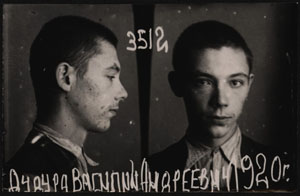

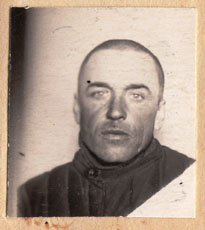

Vasil Dudura, born in 1920 in Ťačov, was arrested in July 1940 crossing the border into the USSR and jailed in Nadvirna. In October he got three years forced labour in Norillag.

Vasil Dudura, born in 1920 in Ťačov, was arrested in July 1940 crossing the border into the USSR and jailed in Nadvirna. In October he got three years forced labour in Norillag.

Vasil Dudura was amnestied on 2 March 1943 but fell in the ranks of the Czechoslovak army in fighting for Kiev in November 1943.

Vasil Dudura was amnestied on 2 March 1943 but fell in the ranks of the Czechoslovak army in fighting for Kiev in November 1943.

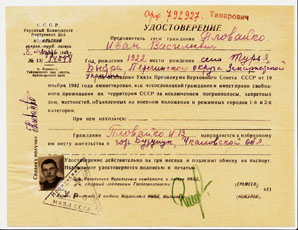

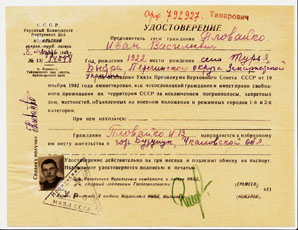

Jan Plovajko was also released from Norillag. He survived not just the Gulag but also the trials of war. He died in 2020 as one of the Czech Republic’s last living witnesses of the Soviet camps.

Jan Plovajko was also released from Norillag. He survived not just the Gulag but also the trials of war. He died in 2020 as one of the Czech Republic’s last living witnesses of the Soviet camps.

On 11 February 1942 Josef Haber from Nový Bohumín was released under the amnesty from Oneglag, where he had been held since June 1940. However, he fell in the Czechoslovak unit’s first battle on the Eastern Front, at Sokolovo, on 8 September 1943.

On 11 February 1942 Josef Haber from Nový Bohumín was released under the amnesty from Oneglag, where he had been held since June 1940. However, he fell in the Czechoslovak unit’s first battle on the Eastern Front, at Sokolovo, on 8 September 1943.

Ignaz Bleiweiss from Brno was released from Volgolag on the same day. He was sentenced to five years forced labour after fleeing racial persecution. He fell on 13 September 1944 at the Battle of Dukla.

Ignaz Bleiweiss from Brno was released from Volgolag on the same day. He was sentenced to five years forced labour after fleeing racial persecution. He fell on 13 September 1944 at the Battle of Dukla.

Ukhta, today a centre of oil extraction in Komi Republic, was the hub of Ukhtizhemlag during the war.

Ukhta, today a centre of oil extraction in Komi Republic, was the hub of Ukhtizhemlag during the war.

Communist Party member Vasil Kis, born in 1915 in Repinoye, escaped so as to avoid serving in the Hungarian army. At the start of 1940 he was sentenced to three years in Ukhtizhemlag.

Communist Party member Vasil Kis, born in 1915 in Repinoye, escaped so as to avoid serving in the Hungarian army. At the start of 1940 he was sentenced to three years in Ukhtizhemlag.

After the amnesty Vasil Kis joined the Czechoslovak army at the start of 1943. He fell in fighting for the Carpathians between 9 and 23 September 1944.

After the amnesty Vasil Kis joined the Czechoslovak army at the start of 1943. He fell in fighting for the Carpathians between 9 and 23 September 1944.

Vasil Kolbasňuk with release papers from Ivdellag during an interview for the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes in 2009.

Vasil Kolbasňuk with release papers from Ivdellag during an interview for the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes in 2009.

Prisoners’ cemetery at one of Sevvostlag’s subsidiary camps in Kolyma. State as of 2013.

Prisoners’ cemetery at one of Sevvostlag’s subsidiary camps in Kolyma. State as of 2013.

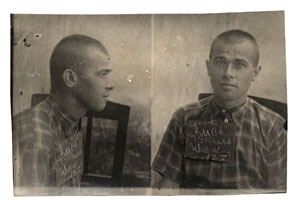

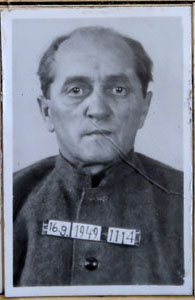

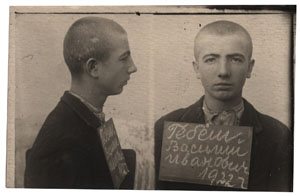

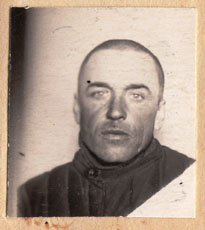

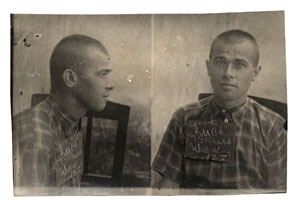

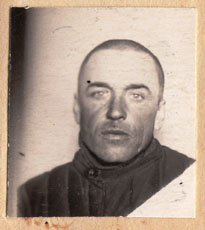

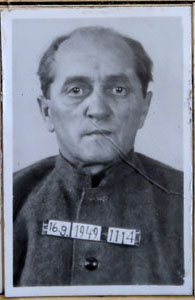

A photograph of Fedor Mikulin from release papers issued at Magadan that permitted him to travel from Kolyma to Buzuluk to the Czechoslovak military unit.

A photograph of Fedor Mikulin from release papers issued at Magadan that permitted him to travel from Kolyma to Buzuluk to the Czechoslovak military unit.

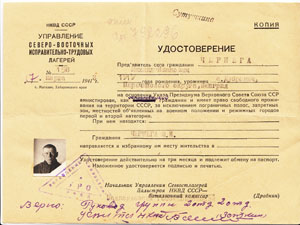

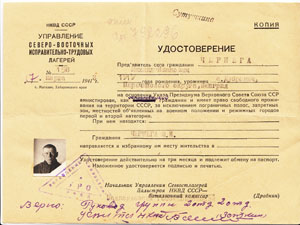

Michal Černěga also survived the notorious camps in Kolyma and deployment in the war. In the 1970s he got in trouble with the Communist regime over his friendship with Egon Bondy and his sons’ signing of Charter 77.

Michal Černěga also survived the notorious camps in Kolyma and deployment in the war. In the 1970s he got in trouble with the Communist regime over his friendship with Egon Bondy and his sons’ signing of Charter 77.

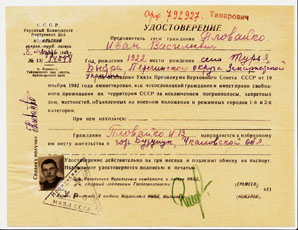

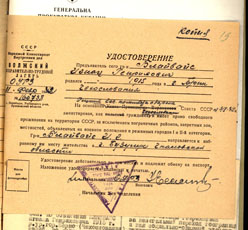

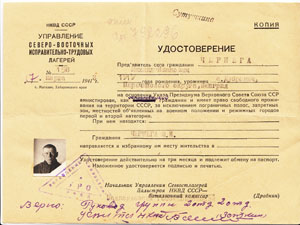

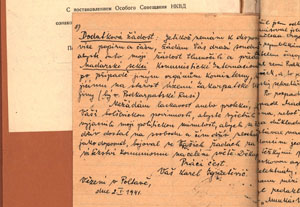

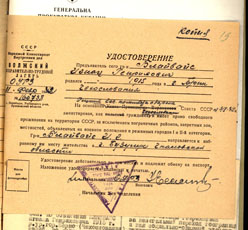

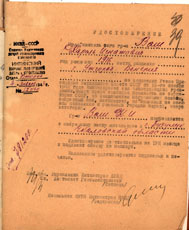

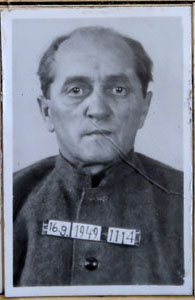

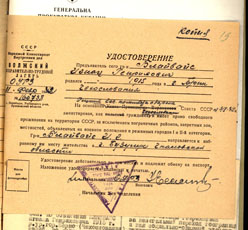

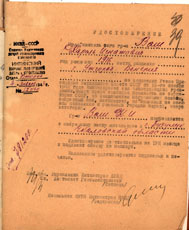

Karel Vaš’s release papers from Intinlag. After 1948 as a Communist prosecutor he was involved in the judicial killings of many democratically minded people, including his Gulag protectors Helidor Píka and Jakub Koutný.

Karel Vaš’s release papers from Intinlag. After 1948 as a Communist prosecutor he was involved in the judicial killings of many democratically minded people, including his Gulag protectors Helidor Píka and Jakub Koutný.

Jakub Koutný, betrayed by Ludvík Svoboda and other brothers in arms who held posts in the totalitarian state following the Communist coup, died on 4 February 1960 after over 10 years in Leopoldov prison.

Jakub Koutný, betrayed by Ludvík Svoboda and other brothers in arms who held posts in the totalitarian state following the Communist coup, died on 4 February 1960 after over 10 years in Leopoldov prison.