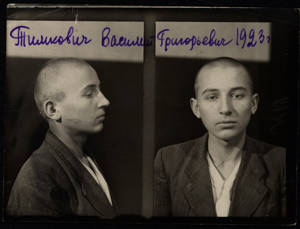

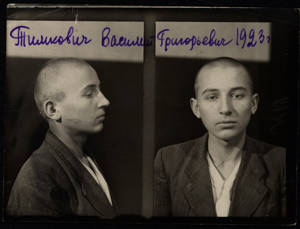

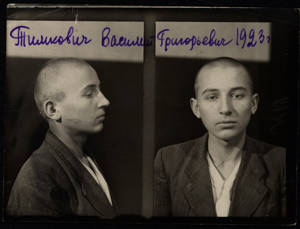

Vasil Timkovič was born in Carpathian Ruthenia in 1923. In 1939 he escaped from occupied Czechoslovakia to the USSR, where he was imprisoned in the Gulag. He spent three years building a railroad in the Pechorlag.

Vasil Timkovič was born in Carpathian Ruthenia in 1923. In 1939 he escaped from occupied Czechoslovakia to the USSR, where he was imprisoned in the Gulag. He spent three years building a railroad in the Pechorlag.

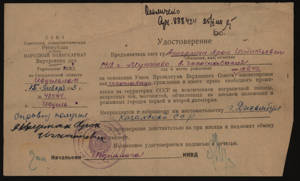

He was released on 19 December 1942. He and Jan Ihnatík are the last two surviving former Gulag prisoners released under an amnesty declared in the Soviet Union 80 years ago. Today he lives in Česká Třebová.

He was released on 19 December 1942. He and Jan Ihnatík are the last two surviving former Gulag prisoners released under an amnesty declared in the Soviet Union 80 years ago. Today he lives in Česká Třebová.

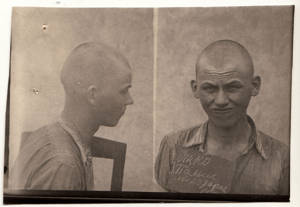

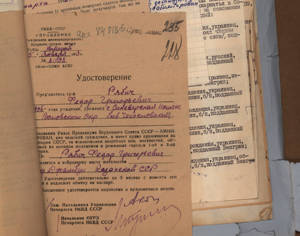

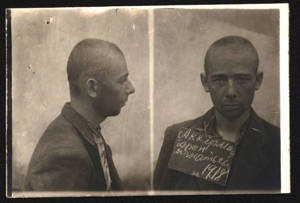

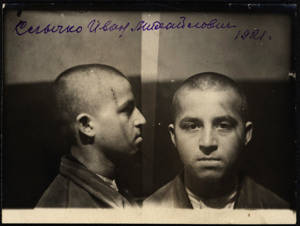

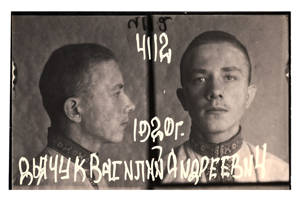

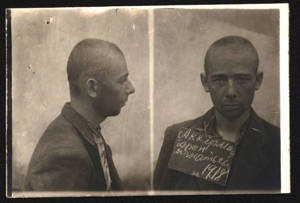

More than eighty years after his arrest in the USSR, Vasil Timkovič received his prison photograph from ÚSTR historians. It comes from one of more than ten thousand NKVD investigative files Czech historians have obtained in Ukrainian archives.

More than eighty years after his arrest in the USSR, Vasil Timkovič received his prison photograph from ÚSTR historians. It comes from one of more than ten thousand NKVD investigative files Czech historians have obtained in Ukrainian archives.

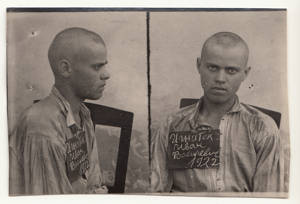

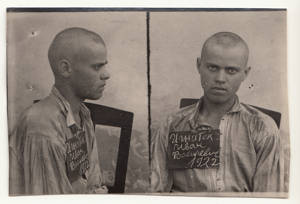

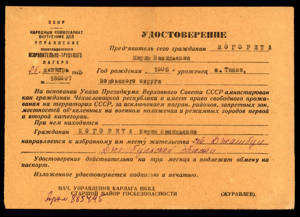

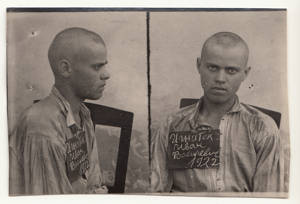

Jan Ihnatík was released from the Uchtizhemlag in December 1942 and joined the Czechoslovak Army in the Soviet Union.

Jan Ihnatík was released from the Uchtizhemlag in December 1942 and joined the Czechoslovak Army in the Soviet Union.

In 2012 Jan Ihnatík gave an interview to Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes historians in Havířov, Czech Republic, where he lives to this day.

In 2012 Jan Ihnatík gave an interview to Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes historians in Havířov, Czech Republic, where he lives to this day.

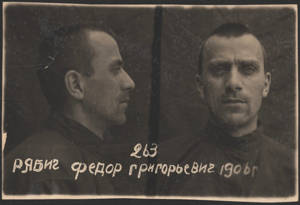

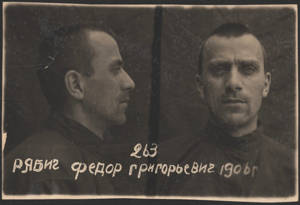

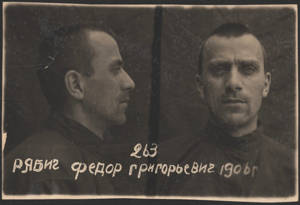

The married couple Fedor Rjabič and Marie Mohoritová-Rjabičová from Carpathian Ruthenia settled in the Czech lands after the war, as did thousands of other inhabitants of the easternmost tip of Czechoslovakia, which was swallowed up by the Soviet Union in 1945.

The married couple Fedor Rjabič and Marie Mohoritová-Rjabičová from Carpathian Ruthenia settled in the Czech lands after the war, as did thousands of other inhabitants of the easternmost tip of Czechoslovakia, which was swallowed up by the Soviet Union in 1945.

The Rjabičs were rightfully proud of their active involvement in fighting on the Eastern Front in the ranks of the Czechoslovak Army. However, like other Carpathian Ruthenians, they held secrets that they were unable to speak about in public in Czechoslovakia, or even in front of their children, Ivan and Miroslav.

The Rjabičs were rightfully proud of their active involvement in fighting on the Eastern Front in the ranks of the Czechoslovak Army. However, like other Carpathian Ruthenians, they held secrets that they were unable to speak about in public in Czechoslovakia, or even in front of their children, Ivan and Miroslav.

His parents never told Miroslav Rjabič, who lives in Příbram, that they had both been prisoners in Soviet Gulag camps after fleeing in good will from occupied Czechoslovakia to the USSR during WWII.

His parents never told Miroslav Rjabič, who lives in Příbram, that they had both been prisoners in Soviet Gulag camps after fleeing in good will from occupied Czechoslovakia to the USSR during WWII.

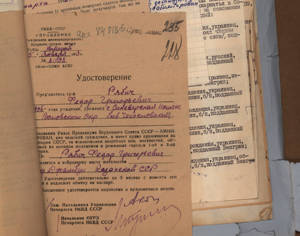

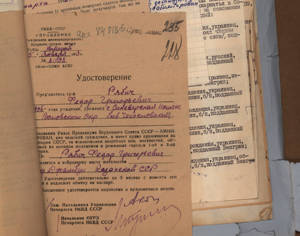

Father of the family Fedor Rjabič was sentenced to three years forced labour in the Uchtizhemlag in northern Russia.

Father of the family Fedor Rjabič was sentenced to three years forced labour in the Uchtizhemlag in northern Russia.

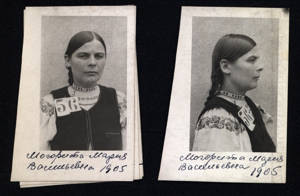

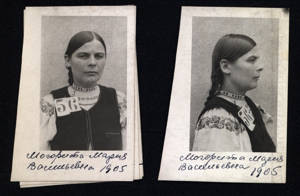

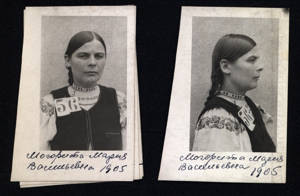

Mother Marie Mohoritová crossed the border into the USSR with her then boyfriend Michal Hrab, who died in the Gulag two years later. She herself lived to see release from the Kargopollag, where she had been sentenced to three years’ forced labour.

Mother Marie Mohoritová crossed the border into the USSR with her then boyfriend Michal Hrab, who died in the Gulag two years later. She herself lived to see release from the Kargopollag, where she had been sentenced to three years’ forced labour.

The Rjabičs and thousands of their compatriots got out thanks to a group of officers in the Czechoslovak mission in the USSR headed by Helidor Píka, who worked for their release.

The Rjabičs and thousands of their compatriots got out thanks to a group of officers in the Czechoslovak mission in the USSR headed by Helidor Píka, who worked for their release.

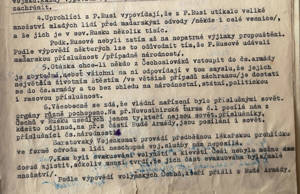

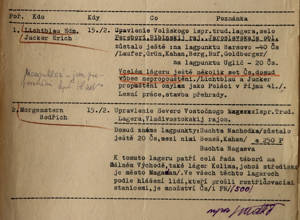

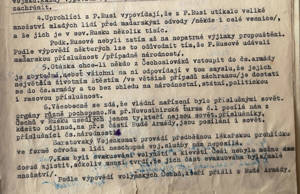

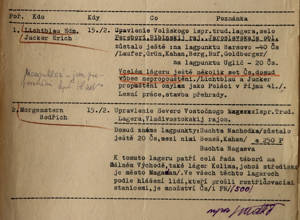

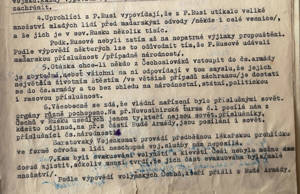

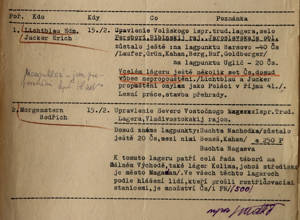

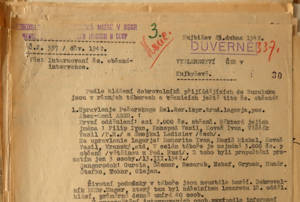

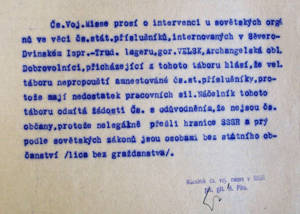

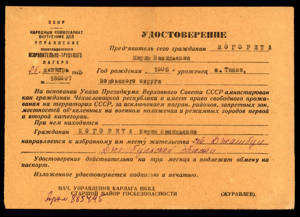

During the war Czechoslovak officers in the USSR interviewed released compatriots with a view to identifying more fellow citizens in Gulag camps.

During the war Czechoslovak officers in the USSR interviewed released compatriots with a view to identifying more fellow citizens in Gulag camps.

Almost four months after the amnesty, released Czechoslovak prisoners reported that thousands of compatriots were still being held in Gulag camps and prisons.

Almost four months after the amnesty, released Czechoslovak prisoners reported that thousands of compatriots were still being held in Gulag camps and prisons.

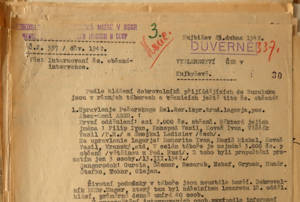

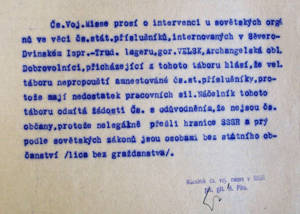

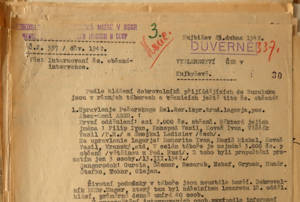

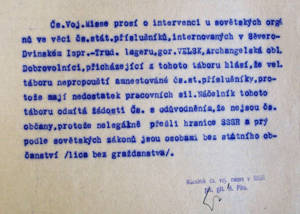

Helidor Píka exhorted the Czechoslovak exile government in London to intervene on behalf of imprisoned refugees.

Helidor Píka exhorted the Czechoslovak exile government in London to intervene on behalf of imprisoned refugees.

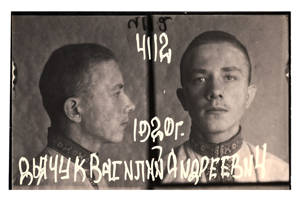

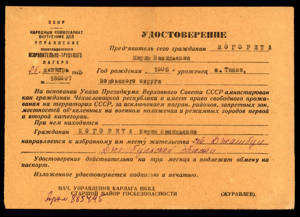

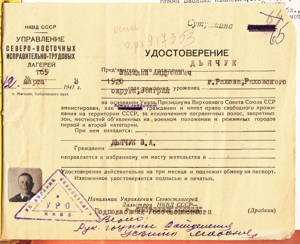

The Soviet leadership agreed to this request on 20 November 1942 with an additional amnesty. Václav Djačuk, imprisoned in the famous Kolyma, was therefore released and could leave from Magadan for the Czechoslovak Army.

The Soviet leadership agreed to this request on 20 November 1942 with an additional amnesty. Václav Djačuk, imprisoned in the famous Kolyma, was therefore released and could leave from Magadan for the Czechoslovak Army.

In 2009 Vácav Djačuk gave an interview to Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes historians on everyday life in the Sevvostlag camps.

In 2009 Vácav Djačuk gave an interview to Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes historians on everyday life in the Sevvostlag camps.

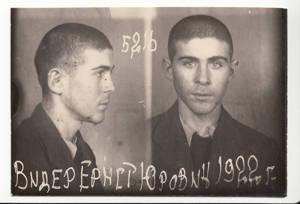

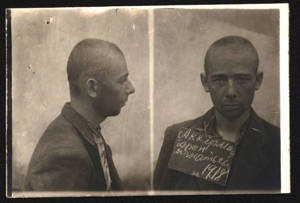

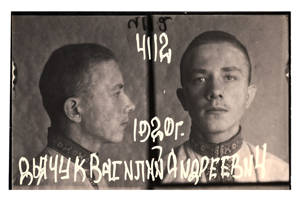

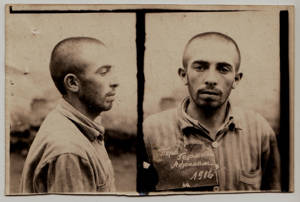

A photograph of Václav Djačuk taken shortly after his arrest was found in a NKVD file held at the State Archive of the Zakarpattia Oblast.

A photograph of Václav Djačuk taken shortly after his arrest was found in a NKVD file held at the State Archive of the Zakarpattia Oblast.

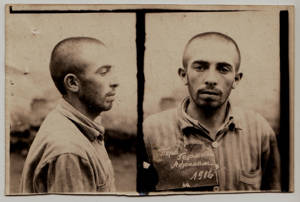

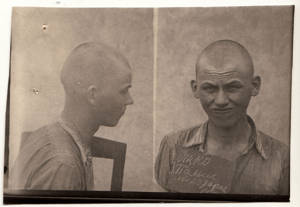

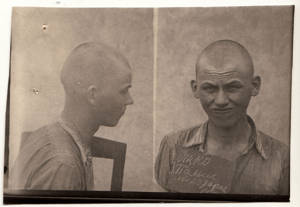

Thousands of files on refugees are preserved at the State Archive of the Zakarpattia Oblast, which also include a prison portrait of Vasila Derďuk.

Thousands of files on refugees are preserved at the State Archive of the Zakarpattia Oblast, which also include a prison portrait of Vasila Derďuk.

Vasil Derďuk was imprisoned in the Vorkutlag, one of the northernmost camps in the Gulag.

Vasil Derďuk was imprisoned in the Vorkutlag, one of the northernmost camps in the Gulag.

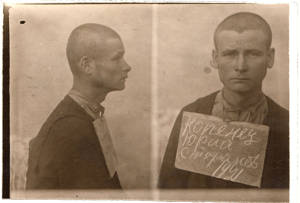

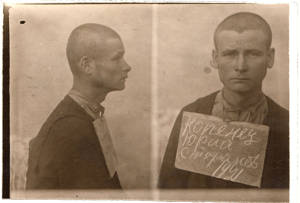

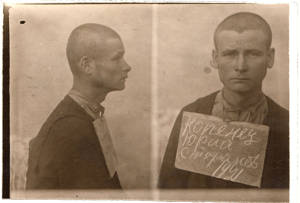

Jiří Kopinec was doing forced labour in the same camp.

Jiří Kopinec was doing forced labour in the same camp.

Jiří Kopinec during an interview with Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes historians in 2008.

Jiří Kopinec during an interview with Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes historians in 2008.

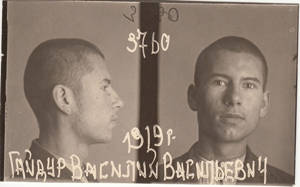

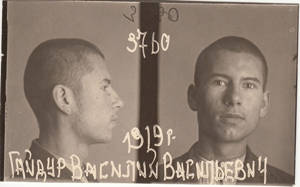

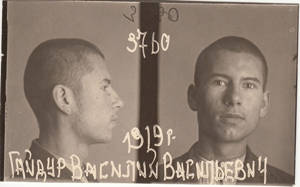

Vasil Hajdur was imprisoned in the Ivdellag.

Vasil Hajdur was imprisoned in the Ivdellag.

In Vasil Hajdur published his memoir From the Gulag via Buzuluk to Prague in 2011 and gave an interview to the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes.

In Vasil Hajdur published his memoir From the Gulag via Buzuluk to Prague in 2011 and gave an interview to the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes.

Pavel Jacko was one of the youngest refugees from Carpathian Ruthenia arrested by the NKVD and sentenced to the Gulag.

Pavel Jacko was one of the youngest refugees from Carpathian Ruthenia arrested by the NKVD and sentenced to the Gulag.

Pavel Jacko survived not only the hardships of investigative prison but forced labour at the Uchtizhemlag and military deployment after the amnesty. In 2010 he gave an interview to the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes.

Pavel Jacko survived not only the hardships of investigative prison but forced labour at the Uchtizhemlag and military deployment after the amnesty. In 2010 he gave an interview to the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes.

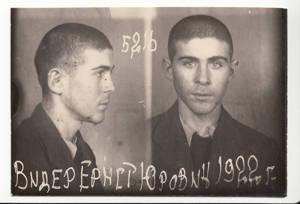

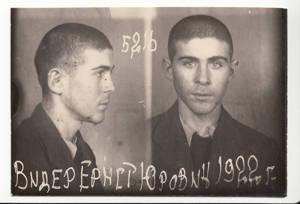

Ernest Vider escaped from service in Hungarian auxiliary units.

Ernest Vider escaped from service in Hungarian auxiliary units.

In 2017 his recollections of the Pechorlag appeared in the book Jews in the Gulag – Soviet Labour and POW Camps in WWII in the Memoirs of Jewish Refugees from Czechoslovakia, published by the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes.

In 2017 his recollections of the Pechorlag appeared in the book Jews in the Gulag – Soviet Labour and POW Camps in WWII in the Memoirs of Jewish Refugees from Czechoslovakia, published by the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes.

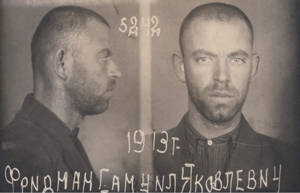

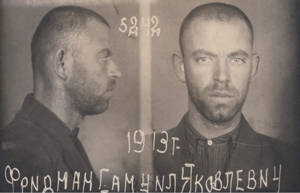

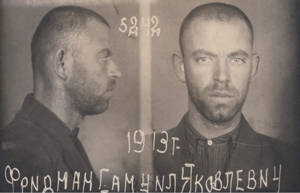

The same book contains an interview with Samuel Friedmann.

The same book contains an interview with Samuel Friedmann.

After his arrest by the NKVD Samuel Friedmann was sentenced to Kolyma, where he mined gold.

After his arrest by the NKVD Samuel Friedmann was sentenced to Kolyma, where he mined gold.

Michal Lar was imprisoned in Ivanov. Though it applied to him, he was not released in the amnesty.

Michal Lar was imprisoned in Ivanov. Though it applied to him, he was not released in the amnesty.

It was not until 1947 that the Soviets allowed him to go home to Nižné Selišče, which is where Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes historians spoke to him in 2010.

It was not until 1947 that the Soviets allowed him to go home to Nižné Selišče, which is where Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes historians spoke to him in 2010.

Herman Perl, who had worked as a locksmith in Brno, was not released either. After fleeing he was sentenced to three years’ labour at Kargopollag, where he died on 8 March 1943.

Herman Perl, who had worked as a locksmith in Brno, was not released either. After fleeing he was sentenced to three years’ labour at Kargopollag, where he died on 8 March 1943.

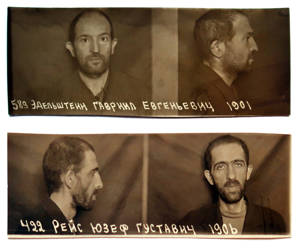

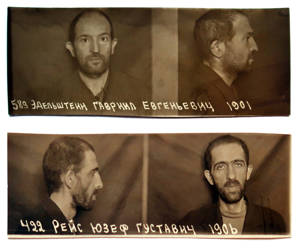

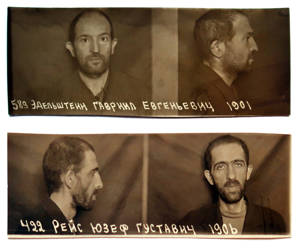

The refugees Gábor Edelstein, a stonemason and Czechoslovak Communist Party member, and Josef Reis, a pharmacist and Czechoslovak Army sub-lieutenant, did not return from the Soviet camps either. Both got 15 years for alleged espionage, and died in the Gulag.

The refugees Gábor Edelstein, a stonemason and Czechoslovak Communist Party member, and Josef Reis, a pharmacist and Czechoslovak Army sub-lieutenant, did not return from the Soviet camps either. Both got 15 years for alleged espionage, and died in the Gulag.

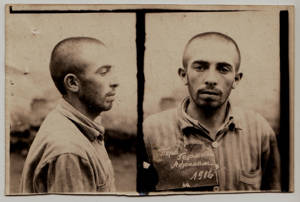

Aron Ackermann was released from the Ivdellag on 16 January 1943 and was sent to the Czechoslovak unit.

Aron Ackermann was released from the Ivdellag on 16 January 1943 and was sent to the Czechoslovak unit.

However, he never made it there. He evidently died at a transit camp.

However, he never made it there. He evidently died at a transit camp.

Lea Moškovic, a member of Hashomer Hatzair in Rachov, was sentenced to three years at the Karlag, where traces of her fate vanish.

Lea Moškovic, a member of Hashomer Hatzair in Rachov, was sentenced to three years at the Karlag, where traces of her fate vanish.

Vasil Kolbasňuk lived to see release from the Vyatlag.

Vasil Kolbasňuk lived to see release from the Vyatlag.

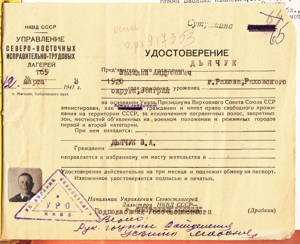

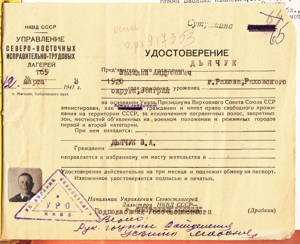

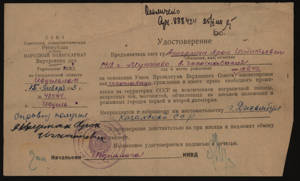

Vasil Kolbasňuk had his Gulag release papers with him during the recording of an interview in Karlovy Vary in 2008.

Vasil Kolbasňuk had his Gulag release papers with him during the recording of an interview in Karlovy Vary in 2008.

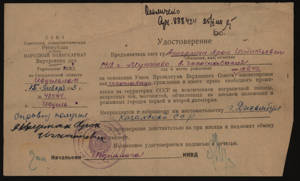

Marie Mohoritová, later Rjabičová, was released from the Kargopollag a month after the additional amnesty, in late November 1942.

Marie Mohoritová, later Rjabičová, was released from the Kargopollag a month after the additional amnesty, in late November 1942.

She was immediately assigned to the Czechoslovak unit in the USSR. On right in picture.

She was immediately assigned to the Czechoslovak unit in the USSR. On right in picture.

Her future husband Fedor Rjabič was released from the Gulag at the start of 1943.

Her future husband Fedor Rjabič was released from the Gulag at the start of 1943.

After being released from a labour camp he entered the Czechoslovak Army (back row, third from left).

After being released from a labour camp he entered the Czechoslovak Army (back row, third from left).

Ivan Rjabič with photos of his parents take by the NKVD after their arrest. During an interview he revealed a further chapter in his father’s chequered life to historians.

Ivan Rjabič with photos of his parents take by the NKVD after their arrest. During an interview he revealed a further chapter in his father’s chequered life to historians.

After the war Fedor Rjabič and Marie Mohoritová settled near the West German border. One day Rjabič led Vasil Sličko, a former Gulag prisoner and comrade-in-arms, across it.

After the war Fedor Rjabič and Marie Mohoritová settled near the West German border. One day Rjabič led Vasil Sličko, a former Gulag prisoner and comrade-in-arms, across it.

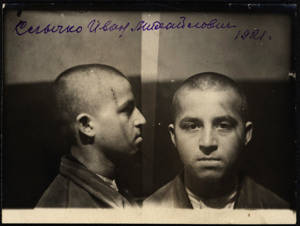

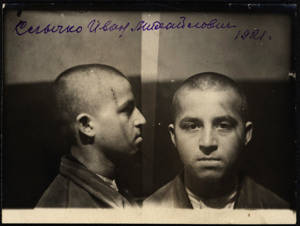

Vasil Sličko was imprisoned at the Ivdellag for illegally crossing the border into the USSR. He was released under the amnesty of 15 January 1943. He succeeded in escaping from Communist Czechoslovakia to West Germany in March 1949.

Vasil Sličko was imprisoned at the Ivdellag for illegally crossing the border into the USSR. He was released under the amnesty of 15 January 1943. He succeeded in escaping from Communist Czechoslovakia to West Germany in March 1949.

In summer 1949 Ivan Sličko, imprisoned in the Gulag between 1939 and 1943, asked Fedor Rjabič to smuggle him to the West. However, the armed group with which he planned to escape was uncovered and arrested. Ivan Sličko was sentenced to 15 years in Czechoslovak labour camps on 13 April 1950.

In summer 1949 Ivan Sličko, imprisoned in the Gulag between 1939 and 1943, asked Fedor Rjabič to smuggle him to the West. However, the armed group with which he planned to escape was uncovered and arrested. Ivan Sličko was sentenced to 15 years in Czechoslovak labour camps on 13 April 1950.

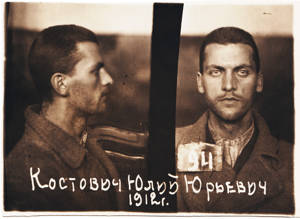

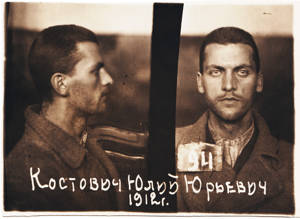

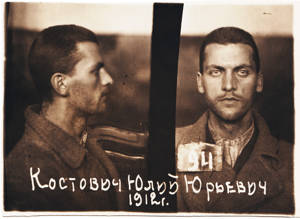

Dozens of former Gulag prisoners were sentenced to prison by the Communist regime. For instance, after his return home Julius Kostovič, a Norillag prisoner, was sentenced to 15 years in a show trial.

Dozens of former Gulag prisoners were sentenced to prison by the Communist regime. For instance, after his return home Julius Kostovič, a Norillag prisoner, was sentenced to 15 years in a show trial.