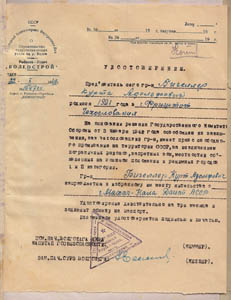

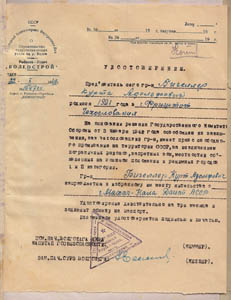

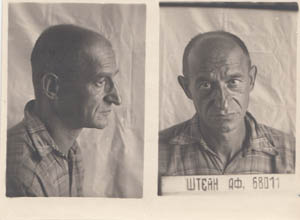

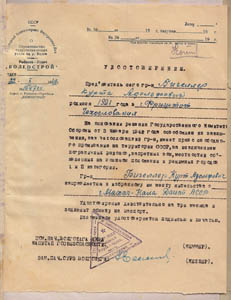

Bedřich Reiss from Ostrava on release papers from the Gulag that allowed him to join the Czechoslovak Army. However, he never saw deployment in battle, instead dying in Buzuluk on 29 October 1942; illness had ended his two-year anabasis through Nazi and Soviet camps and prisons.

Bedřich Reiss from Ostrava on release papers from the Gulag that allowed him to join the Czechoslovak Army. However, he never saw deployment in battle, instead dying in Buzuluk on 29 October 1942; illness had ended his two-year anabasis through Nazi and Soviet camps and prisons.

The grim wanderings of Bedřich Reiss and another 1,500 or so Jews from the Protectorate began in the latter half of October 1939 at Ostrava train station. Those events are commemorated by an inconspicuous and damaged memorial.

The grim wanderings of Bedřich Reiss and another 1,500 or so Jews from the Protectorate began in the latter half of October 1939 at Ostrava train station. Those events are commemorated by an inconspicuous and damaged memorial.

The first deportation transport of Jews in WWII was from here. This was followed by transports from Vienna and Katowice, where 5,000 men were forcibly resettled with the aim of preparing the ground for the establishment of a Jewish reservation in the east of Nazi-occupied Poland.

The first deportation transport of Jews in WWII was from here. This was followed by transports from Vienna and Katowice, where 5,000 men were forcibly resettled with the aim of preparing the ground for the establishment of a Jewish reservation in the east of Nazi-occupied Poland.

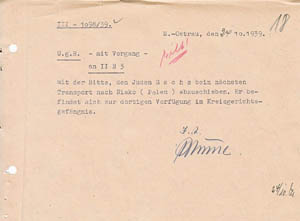

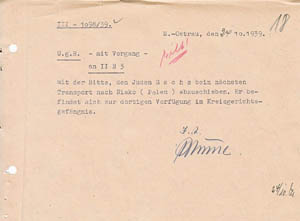

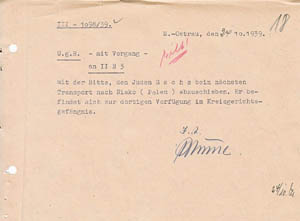

The organiser of the operation, which preceded the “final solution”, the extermination of Europe’s Jews, was Adolf Eichmann. In a telegram to the Ostrava Gestapo dated 15 October 1939 he states that the transport’s destination will be Nisko.

The organiser of the operation, which preceded the “final solution”, the extermination of Europe’s Jews, was Adolf Eichmann. In a telegram to the Ostrava Gestapo dated 15 October 1939 he states that the transport’s destination will be Nisko.

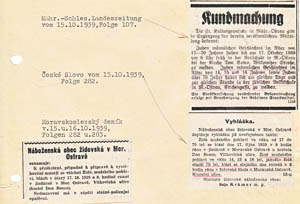

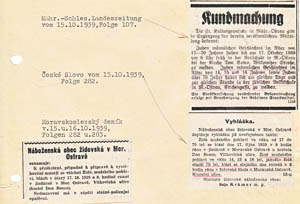

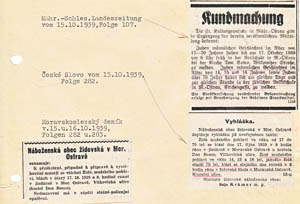

The Gestapo kept records of reports on the transports that appeared in the local press. In this case it concerns a call from the Ostrava Jewish community for men to join the scheduled transports, which it was forced to do by the Nazis.

The Gestapo kept records of reports on the transports that appeared in the local press. In this case it concerns a call from the Ostrava Jewish community for men to join the scheduled transports, which it was forced to do by the Nazis.

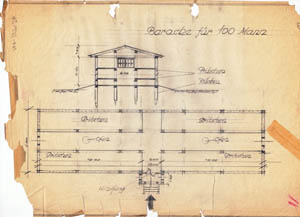

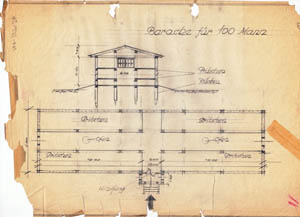

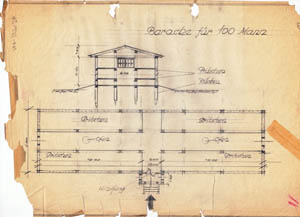

Sketches of camp buildings, which prisoners were to build themselves, have been preserved at the Moravian Provincial Archive in Brno.

Sketches of camp buildings, which prisoners were to build themselves, have been preserved at the Moravian Provincial Archive in Brno.

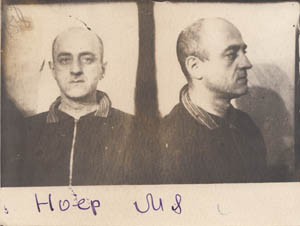

The Moravian Provincial Archive in Brno houses a number of personal files of those deported to Nisko, including Siegmund Sachs, photographed following his arrest by the Gestapo in 1939.

The Moravian Provincial Archive in Brno houses a number of personal files of those deported to Nisko, including Siegmund Sachs, photographed following his arrest by the Gestapo in 1939.

The Jewish community failed to supply the requested number of deportees so the Nazis included in the transport prisoners of Jewish origin from Brno, Prague and other places in the Protectorate.

The Jewish community failed to supply the requested number of deportees so the Nazis included in the transport prisoners of Jewish origin from Brno, Prague and other places in the Protectorate.

The station in Nisko – destination of all the transports within Operation Nisko.

The station in Nisko – destination of all the transports within Operation Nisko.

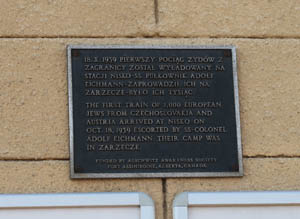

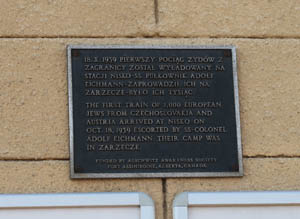

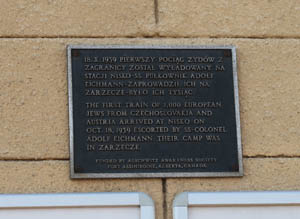

A plaque memorialising events back then hangs over station timetables.

A plaque memorialising events back then hangs over station timetables.

A plaque in Nisko commemorates the sad primary status of Ostrava Jews deported by Adolf Eichmann.

A plaque in Nisko commemorates the sad primary status of Ostrava Jews deported by Adolf Eichmann.

From the station in Nisko deportees had to set off on foot beyond the town and the river San.

From the station in Nisko deportees had to set off on foot beyond the town and the river San.

Deported men were to build a camp above the river San, left of the village of Zarzece.

Deported men were to build a camp above the river San, left of the village of Zarzece.

Drawing of the camp at Zarzecze by former prisoner Leo Haas.

Drawing of the camp at Zarzecze by former prisoner Leo Haas.

Most of the territory of the former camp is now covered in houses.

Most of the territory of the former camp is now covered in houses.

A plaque installed on a stone in front of the former camp on the anniversary of the transports in 2019 was stolen in 2021.

A plaque installed on a stone in front of the former camp on the anniversary of the transports in 2019 was stolen in 2021.

For 10 years now ÚSTR has been researching in the Ukrainian archives the stories of Czechs imprisoned in the USSR, including those deported to Nisko. Jan Horník and Jan Dvořák compare Gestapo deportation lists with an inventory of names at the State Archive in Lviv.

For 10 years now ÚSTR has been researching in the Ukrainian archives the stories of Czechs imprisoned in the USSR, including those deported to Nisko. Jan Horník and Jan Dvořák compare Gestapo deportation lists with an inventory of names at the State Archive in Lviv.

Adam Hradilek in the cellars of the former KGB archive in Lviv that opened up to Czech historians after 2014. Wearing a headband light, he selects files of Jewish refugees arrested during the war in the Lviv Oblast for random research.

Adam Hradilek in the cellars of the former KGB archive in Lviv that opened up to Czech historians after 2014. Wearing a headband light, he selects files of Jewish refugees arrested during the war in the Lviv Oblast for random research.

Among the thousands of files on refugees arrested by the NKVD in the Lviv Oblast, historians have also found hundreds on Czechs who escaped from the Protectorate or were deported to Nisko. Jan Horník and Jan Dvořák go through the files in an improvised research room at a former prison on Loncky St.

Among the thousands of files on refugees arrested by the NKVD in the Lviv Oblast, historians have also found hundreds on Czechs who escaped from the Protectorate or were deported to Nisko. Jan Horník and Jan Dvořák go through the files in an improvised research room at a former prison on Loncky St.

Among the documents uncovered is the file of Hermann Engelmann from Šenov, who after being driven out of Nisko and arrested by the NKVD in Lviv was sentenced to the Volgolag. He was released from the camp on 3 March 1942 and taken to Buzuluk, where, however, he died after six days.

Among the documents uncovered is the file of Hermann Engelmann from Šenov, who after being driven out of Nisko and arrested by the NKVD in Lviv was sentenced to the Volgolag. He was released from the camp on 3 March 1942 and taken to Buzuluk, where, however, he died after six days.

A number of family photographs which Hermann Engelmann brought with him on the transport to Nisko, and which the NKVD confiscated following his arrest in Lviv, are preserved in his file.

A number of family photographs which Hermann Engelmann brought with him on the transport to Nisko, and which the NKVD confiscated following his arrest in Lviv, are preserved in his file.

Eighteen-year-old Jan Fišer, hauled off from Ostrava to Nisko, was eventually released from the Gulag and joined the Czechoslovak Army. However, he fell in a battle by the village of Yachnovshchina in Ukraine on 13 October 1943.

Eighteen-year-old Jan Fišer, hauled off from Ostrava to Nisko, was eventually released from the Gulag and joined the Czechoslovak Army. However, he fell in a battle by the village of Yachnovshchina in Ukraine on 13 October 1943.

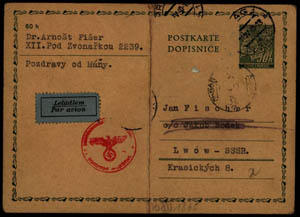

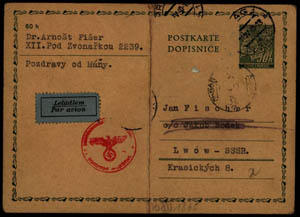

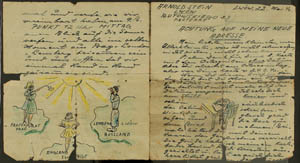

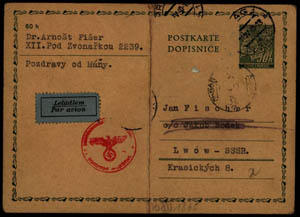

Mail that he received in Lviv from his brother Arnošt in Prague is preserved in his NKVD file.

Mail that he received in Lviv from his brother Arnošt in Prague is preserved in his NKVD file.

In it he describes the situation of relatives in the Protectorate. Most of them did not survive the Nazi frenzy of the following years. In 1942 Arnošt Fišer was himself deported east to the ghetto in Zamość, where he died in unknown circumstances.

In it he describes the situation of relatives in the Protectorate. Most of them did not survive the Nazi frenzy of the following years. In 1942 Arnošt Fišer was himself deported east to the ghetto in Zamość, where he died in unknown circumstances.

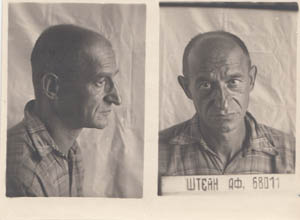

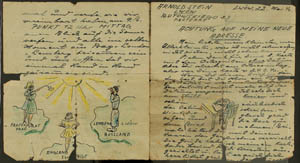

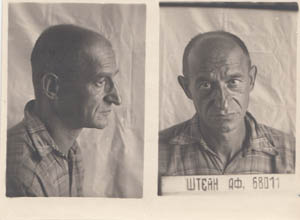

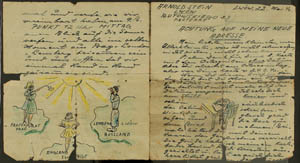

One file is dedicated to the case of Arnold Stein from Karlovy Vary. He was jailed by the Nazis for attempting to escape to Poland and subsequently deported to Nisko. His daughter Gerda was saved by a children’s transport to the UK, while his wife Erna died at Auschwitz. He too corresponded with his family until his arrest.

One file is dedicated to the case of Arnold Stein from Karlovy Vary. He was jailed by the Nazis for attempting to escape to Poland and subsequently deported to Nisko. His daughter Gerda was saved by a children’s transport to the UK, while his wife Erna died at Auschwitz. He too corresponded with his family until his arrest.

In one letter Stein drew himself in Lviv, his daughter Gerda in London and wife Erna and step-daughter Johanna in Prague, calling on them all to join together in looking toward the sun on 9 June 1940. Two weeks later he was arrested by the NKVD and sentenced to the Gulag, where he died.

In one letter Stein drew himself in Lviv, his daughter Gerda in London and wife Erna and step-daughter Johanna in Prague, calling on them all to join together in looking toward the sun on 9 June 1940. Two weeks later he was arrested by the NKVD and sentenced to the Gulag, where he died.

Rudolf Goldflam was deported from Brno with his three brothers. After escaping from Lviv all four were arrested by the NKVD. Rudolf and Viktor ended up in the Gulag…

Rudolf Goldflam was deported from Brno with his three brothers. After escaping from Lviv all four were arrested by the NKVD. Rudolf and Viktor ended up in the Gulag…

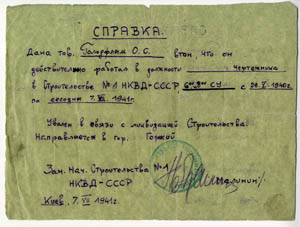

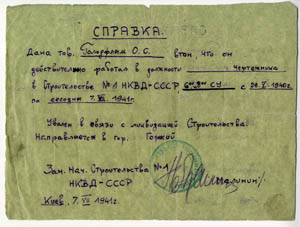

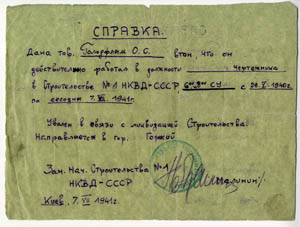

… and their brothers Bedřich and Otto (father of the actor and writer Arnošt Goldflam) were arrested and then used as forced labour on the construction of NKVD building No. 1 in Kyiv. All four survived Nazi and Soviet persecution and after being deployed during the war returned to Czechoslovakia.

… and their brothers Bedřich and Otto (father of the actor and writer Arnošt Goldflam) were arrested and then used as forced labour on the construction of NKVD building No. 1 in Kyiv. All four survived Nazi and Soviet persecution and after being deployed during the war returned to Czechoslovakia.

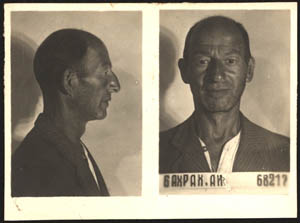

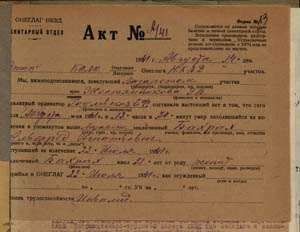

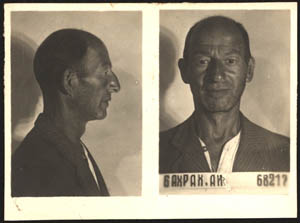

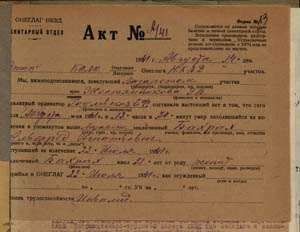

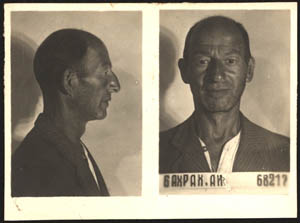

Lawyer Alfred Bachrach from Místek was not so lucky. He was arrested by the NKVD in Lviv on 30 June 1940…

Lawyer Alfred Bachrach from Místek was not so lucky. He was arrested by the NKVD in Lviv on 30 June 1940…

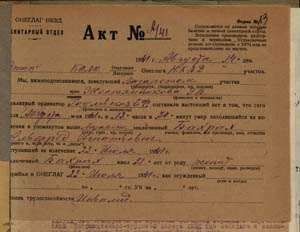

… and died at the age of 51 on 4 August 1941 in Oneglag’s sanitary unit.

… and died at the age of 51 on 4 August 1941 in Oneglag’s sanitary unit.

Locksmith Emil Laufer from Ostrava died on 13 April 1942 in Buzuluk, a month after being released from the Gulag.

Locksmith Emil Laufer from Ostrava died on 13 April 1942 in Buzuluk, a month after being released from the Gulag.

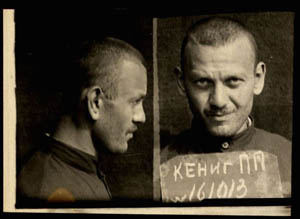

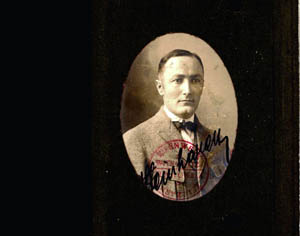

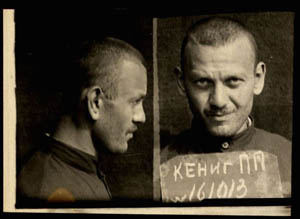

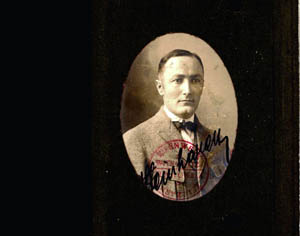

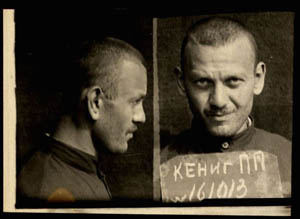

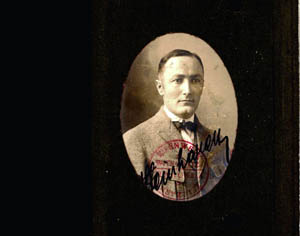

Prior to the transport to Nisko Josef König lived in Brno and Olomouc. A photograph of him in civilian attire, which was confiscated during arrest and a search of his person, is preserved in the NKVD file.

Prior to the transport to Nisko Josef König lived in Brno and Olomouc. A photograph of him in civilian attire, which was confiscated during arrest and a search of his person, is preserved in the NKVD file.

After release from the Gulag Josef König joined the Czechoslovak Army. He died in its ranks during the Battle of Sokolovo on 10 March 1943.

After release from the Gulag Josef König joined the Czechoslovak Army. He died in its ranks during the Battle of Sokolovo on 10 March 1943.

Arnošt Bleiweiss also fell at Sokolovo.

Arnošt Bleiweiss also fell at Sokolovo.

While Eugen Presser died at the momentous Battle of Sokolov, his brother Leopold survived the hardships of war and lived out the rest of his life in Israel under the name Jehuda Parma. He was one of three surviving witnesses of the transports to Niska interviewed by ÚSTR historians. He died in 2016.

While Eugen Presser died at the momentous Battle of Sokolov, his brother Leopold survived the hardships of war and lived out the rest of his life in Israel under the name Jehuda Parma. He was one of three surviving witnesses of the transports to Niska interviewed by ÚSTR historians. He died in 2016.

Another survivor of the transport to Nisko, Bedřich Seliger, remained alive in the Czech Republic until 2012.

Another survivor of the transport to Nisko, Bedřich Seliger, remained alive in the Czech Republic until 2012.

Transport survivor Otto Winecki settled after the war in Australia, where ÚSTR conducted an interview with him in 2014. He died in 2015.

Transport survivor Otto Winecki settled after the war in Australia, where ÚSTR conducted an interview with him in 2014. He died in 2015.

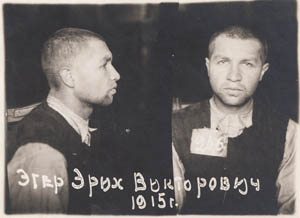

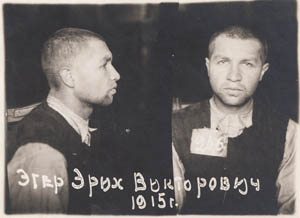

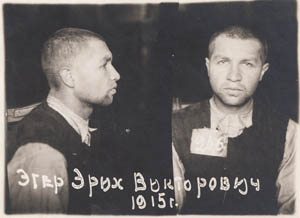

Erich Egger, together with his brother Karel, managed to escape from Ostrava prior to the transport to Nisko. Both were arrested by the NKVD in Lviv and sentenced to the Ukhtizhemlag, where Erich died.

Erich Egger, together with his brother Karel, managed to escape from Ostrava prior to the transport to Nisko. Both were arrested by the NKVD in Lviv and sentenced to the Ukhtizhemlag, where Erich died.

His brother Karel lived to see amnesty and was released to Buzuluk. He was captured by the Nazis at the Battle of Sokolovo and returned to the Protectorate.

His brother Karel lived to see amnesty and was released to Buzuluk. He was captured by the Nazis at the Battle of Sokolovo and returned to the Protectorate.

Along with other POWs he was used for anti-Soviet and anti-Beneš propaganda in 1943, before evidently being executed. Pictured being interviewed by Protectorate journalists in the propaganda book Prisoners of War Testify.

Along with other POWs he was used for anti-Soviet and anti-Beneš propaganda in 1943, before evidently being executed. Pictured being interviewed by Protectorate journalists in the propaganda book Prisoners of War Testify.

Brno man Ignác Beiweiss was sentenced to five years’ forced labour in the Gulag for escaping to the USSR. After being released and joining the Czechoslovak Army he took part in a number of battles, the last of which was at Dukla, where he fell on 13 September 1944.

Brno man Ignác Beiweiss was sentenced to five years’ forced labour in the Gulag for escaping to the USSR. After being released and joining the Czechoslovak Army he took part in a number of battles, the last of which was at Dukla, where he fell on 13 September 1944.

Prior to being deported to Nisko, Holíč-born Artur Eisinger was imprisoned by the Nazis at Ivančice in Brno. He was not released during the amnesty and died at Volgolag on 4 January 1943.

Prior to being deported to Nisko, Holíč-born Artur Eisinger was imprisoned by the Nazis at Ivančice in Brno. He was not released during the amnesty and died at Volgolag on 4 January 1943.

Heřman Bisenz from Mikulova also failed to see the amnesty, dying at Oneglag on 3 November 1941, two months before it was declared.

Heřman Bisenz from Mikulova also failed to see the amnesty, dying at Oneglag on 3 November 1941, two months before it was declared.

Vilém Steinhardt from Ostrava made it through the hardships of Nazi persecution and the Soviet Gulag, though soon after his release from a Soviet labour camp he died among his compatriots at Buzuluk on 7 March 1942.

Vilém Steinhardt from Ostrava made it through the hardships of Nazi persecution and the Soviet Gulag, though soon after his release from a Soviet labour camp he died among his compatriots at Buzuluk on 7 March 1942.

The NKVD file of Villém Steinhardt contains many personal documents, including a receipt for turning in a radio to the Gestapo in Vítkovice.

The NKVD file of Villém Steinhardt contains many personal documents, including a receipt for turning in a radio to the Gestapo in Vítkovice.

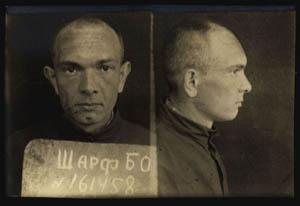

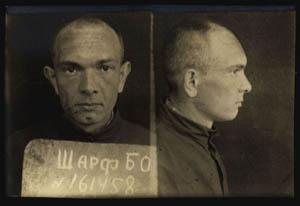

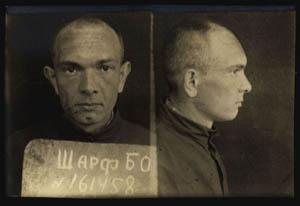

Bedřich Scharf, a native of Hrušov released from Volgolag, died as a Czechoslovak soldier near Kharkiv on 14 March 1943.

Bedřich Scharf, a native of Hrušov released from Volgolag, died as a Czechoslovak soldier near Kharkiv on 14 March 1943.

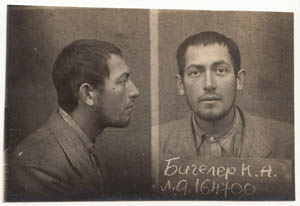

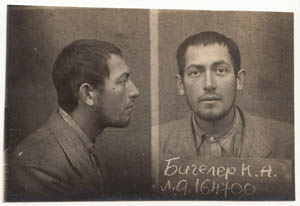

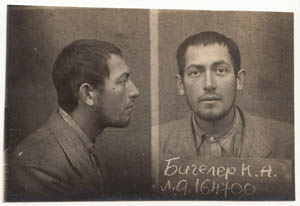

Karel Borský was born as Kurt Bihler in Fryštát. After being deported to Nisko and forced onto Soviet territory he was sentenced to three years forced labour in the Gulag and sent to Volgolag.

Karel Borský was born as Kurt Bihler in Fryštát. After being deported to Nisko and forced onto Soviet territory he was sentenced to three years forced labour in the Gulag and sent to Volgolag.

Karel Borský was released from Volgolag as a Czechoslovak citizen and joined the Czechoslovak Army in Buzuluk. He died in Prague in 2001.

Karel Borský was released from Volgolag as a Czechoslovak citizen and joined the Czechoslovak Army in Buzuluk. He died in Prague in 2001.

Among those who survived the hardships of WWII was also Moritz Friedner, who lived in Bruntál after the war.

Among those who survived the hardships of WWII was also Moritz Friedner, who lived in Bruntál after the war.

Emil Strebinger from Ostrava was arrested by the NKVD in Lviv. Strebinger managed to survive both Nazi and Soviet persecution as well as fighting on the Eastern Front. He died on Ostrava on 5 December 1965.

Emil Strebinger from Ostrava was arrested by the NKVD in Lviv. Strebinger managed to survive both Nazi and Soviet persecution as well as fighting on the Eastern Front. He died on Ostrava on 5 December 1965.

Among the documents confiscated by the NVKD found in Emil Strebinger’s file was his Czechoslovak passport.

Among the documents confiscated by the NVKD found in Emil Strebinger’s file was his Czechoslovak passport.

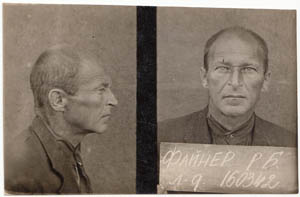

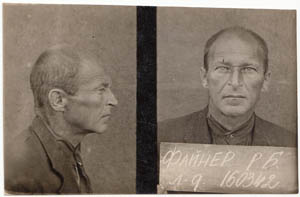

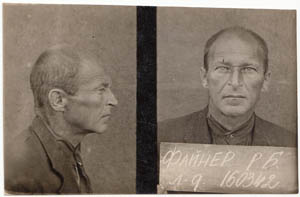

After deportation to Nisko, Robert Feiner was imprisoned at the Nazis’ Zarzece camp until December 1939. At the end of June 1940 he was arrested by the NKVD in Lviv and sentenced to the Gulag. After being released he returned to Czechoslovakia as a soldier of the Czechoslovak Army.

After deportation to Nisko, Robert Feiner was imprisoned at the Nazis’ Zarzece camp until December 1939. At the end of June 1940 he was arrested by the NKVD in Lviv and sentenced to the Gulag. After being released he returned to Czechoslovakia as a soldier of the Czechoslovak Army.

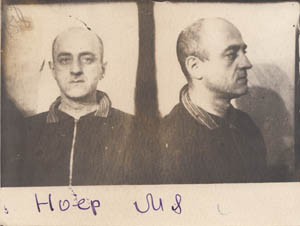

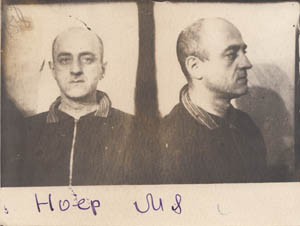

Marek Neuer studied medicine in Brno, where in September 1939 he was arrested by the Nazis and deported to Nisko. After escaping to Soviet territory he was sentenced to three years in the Gulag. He served as a doctor at Kandalakshlag. Following his release he fought as a member of the Czechoslovak Army. In 1949 he left for Israel, where he died in 1972.

Marek Neuer studied medicine in Brno, where in September 1939 he was arrested by the Nazis and deported to Nisko. After escaping to Soviet territory he was sentenced to three years in the Gulag. He served as a doctor at Kandalakshlag. Following his release he fought as a member of the Czechoslovak Army. In 1949 he left for Israel, where he died in 1972.

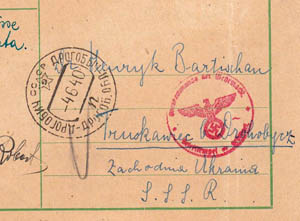

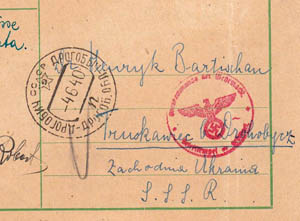

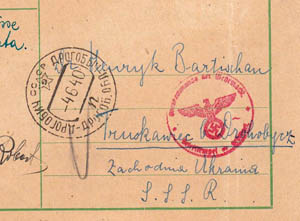

The stamps of totalitarian powers on correspondence confiscated by the NKVD in Lviv illustrate the desperate position of refugees from Nazism who found themselves on Soviet territory.

The stamps of totalitarian powers on correspondence confiscated by the NKVD in Lviv illustrate the desperate position of refugees from Nazism who found themselves on Soviet territory.

The original town name sign seen by those on board the first transport from occupied Czechoslovakia is itself a powerful reminder of tragic events.

The original town name sign seen by those on board the first transport from occupied Czechoslovakia is itself a powerful reminder of tragic events.