FROM NAZI PRISONS AND CAMPS TO THE SOVIET GULAG:

THE FATES OF CZECH JEWS FROM THE TRANSPORT TO NISKO

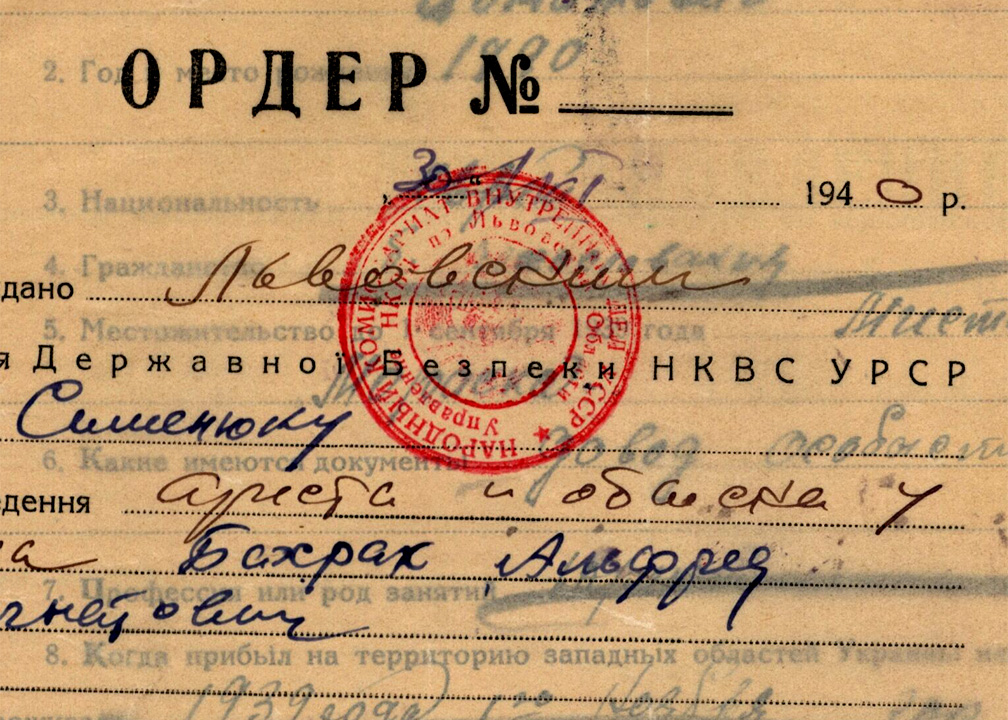

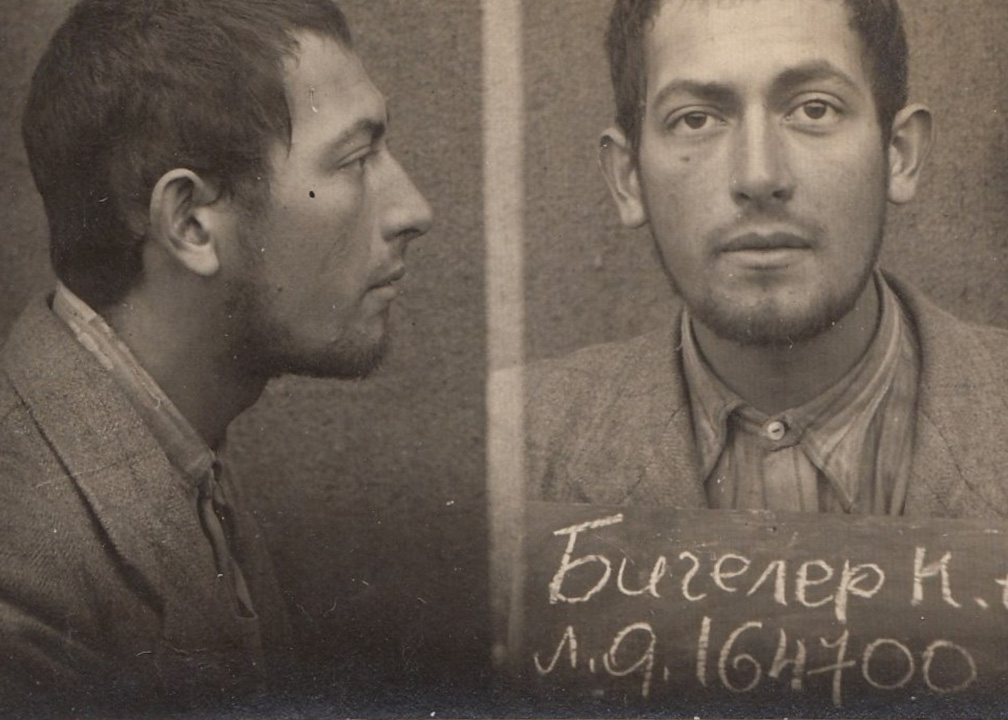

The end of June 1940 saw the culmination of a wave of arrests of refugees from Nazism by the Soviet secret police NKVD on the Soviet-occupied part of Eastern Poland. Among the tens of thousands of mainly Jewish refugees arrested were also hundreds of Czech Jews, for the most part detained in Lviv and its environs. Some were persons fleeing their occupied homeland independently. However, the majority were Czechs deported by the Nazis some months previously to Nisko, on the San River. Instead of in Nazis camps, most ended up in Soviet prisons and Gulag labour camps. In cooperation with the Archive of the Security Service of Ukraine and the Department of Cybernetics at the University of West Bohemia in Pilsen, the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes (ÚSTR) is publishing the first two hundred NKVD investigation files on the subject found in the Ukrainian archives.

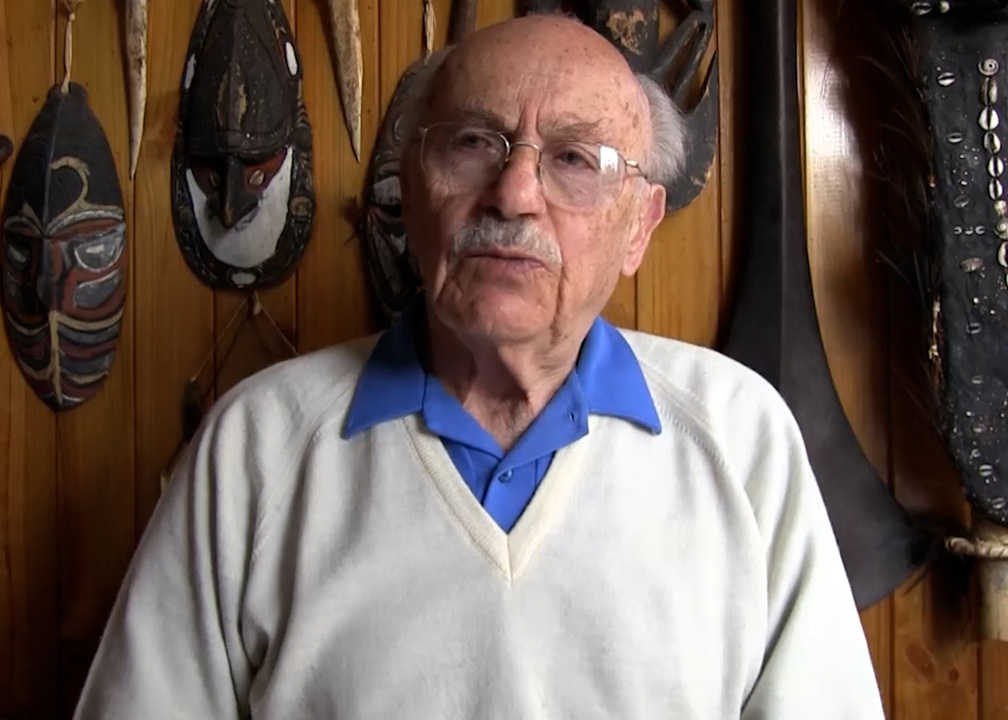

ÚSTR is simultaneously issuing a themed photo gallery, a list of deportees imprisoned in the USSR, short biographies of selected victims and interviews with survivors J. Parma, B. Seliger and O. Winecký, with whom the institute’s staff succeeded in speaking, and other accompanying texts on the subject gathered within the project Czechoslovaks in the Gulag.

The published materials represent a fragment of the archival collection of over 5,000 investigation files on Jewish refugees from Nazi-occupied parts of Europe (f. R – Jewish files (1939–1941), held at the Archive of the Security Service of Ukraine in Lviv (ASBU Lviv), which ÚSTR has digitalised in recent years. The fond contains for instance hundreds of files on persons deported to Nisko from occupied Poland and Austria. Despite the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, ÚSTR is continuing to do research and digitalise archival materials related to this subject with its Ukrainian partners. In particular the State Archive of the Lviv Oblast (DALO) and the Departmental State Archive of the Security Service of Ukraine (HDA SBU), which contain a volume of hitherto unprocessed files on the subject of refugees from Nazism persecuted in the USSR that are awaiting digitalisation and publication.

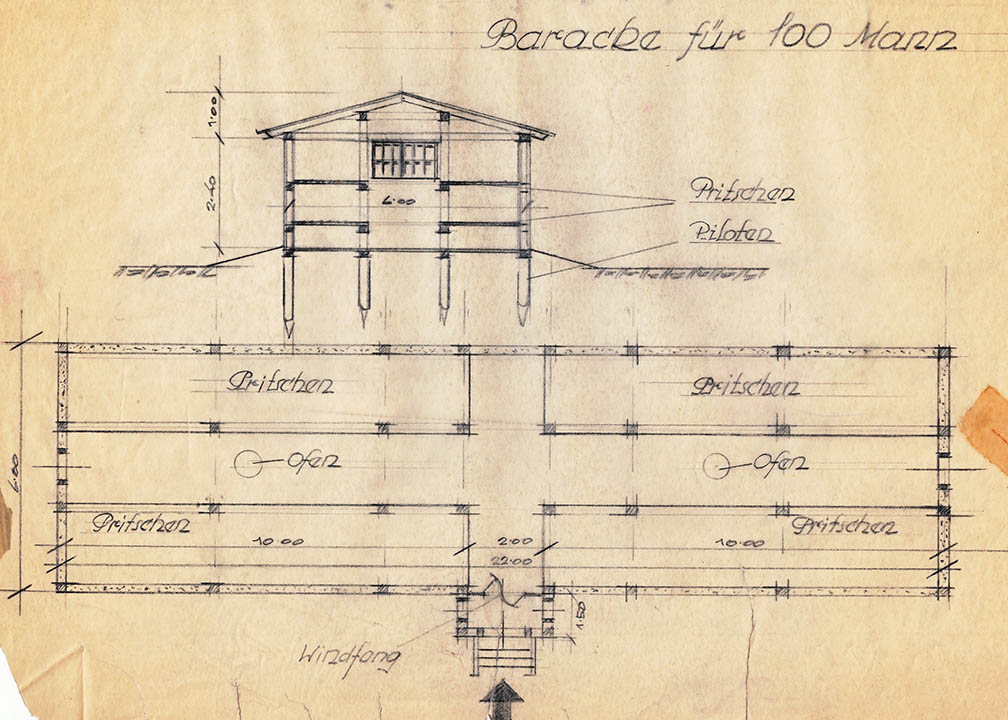

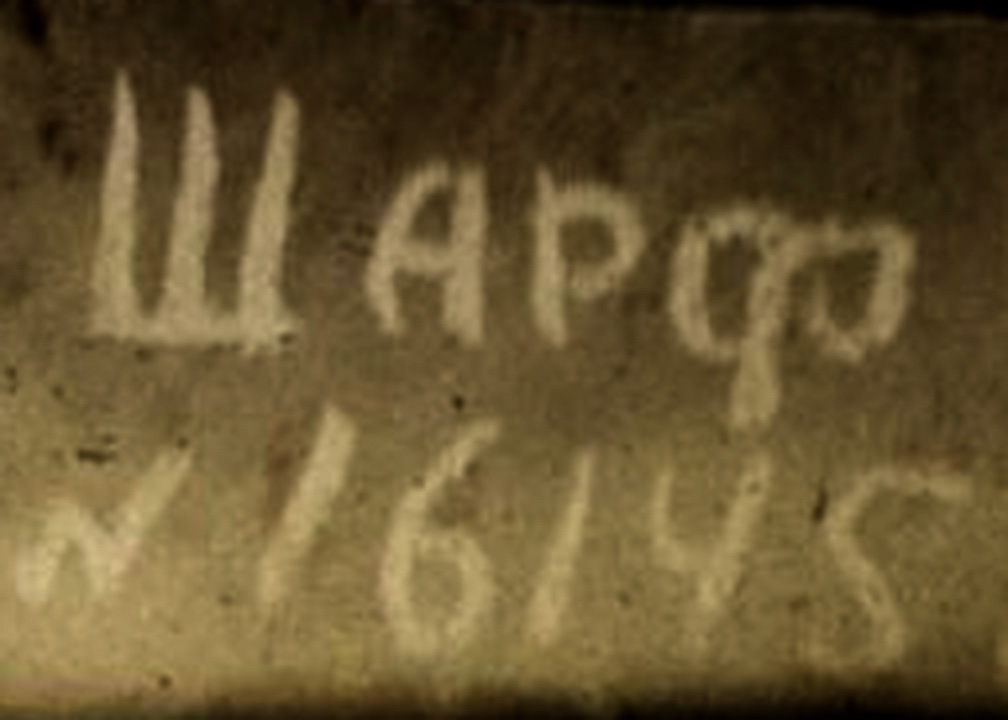

What was called Operation Nisko, one of the first Nazi plans to “solve the Jewish question”, was carried out in autumn 1939. The operation was intended to create a Jewish reservation in the east of the Nazi-occupied part of Poland. In the first phase selected Jewish males over 14 were deported from Moravská Ostrava, Katowice and Vienna. This was organised by the Gestapo and the Central Office for Jewish Emigration in Vienna and in Prague under Adolf Eichmann, who personally selected the site of the first camp on the outskirts of the village of Zarzecze near Nisko. Between 17 and 26 October over 5,000 persons were deported. While the first transport was still on its way, the Nazi leadership decided to cancel the operation. Around 500 deportees remained in the Zarzecze concentration camp. Over 4,000 were driven onto Soviet territory by SS officers; some of the Jews who were left at the camp also escaped there later. Of the 1,500 men deported from the Czech lands, around 300 returned to the Protectorate ( see working list), with the majority later dying in Nazi concentration camps. Around 1,000 found themselves on Soviet territory and, with few exceptions, were arrested by NKVD officers as a part of a “clean-up” of the USSR’s borderlands in summer 1940. This was followed by imprisonment in Gulag camps, special labour colonies, collective farms or construction projects overseen by the NKVD throughout the Soviet Union.

Jewish refugees who were not arrested or evacuated to the Soviet interior were for the most part murdered following the Nazi attack on the USSR in June 1941.

The majority of Jewish refugees from the Protectorate were released from the Gulag in 1942 on the basis of an amnesty for Czechoslovak citizens imprisoned in the USSR that allowed them to enter a nascent Czechoslovak military unit in the USSR. Several dozen Jews from the Ostrava and Těšín areas who declared themselves to be of Polish nationality had been freed from Soviet camps within an amnesty for Poles some months earlier. However, a study of published files shows that 20 percent did not survive the Gulag, such as E. Gessler, who died at Unzhlag, or W. Morgenstern in the Oneglag. Others died of illness on arrival in Buzuluk, such as E. Blum.

Some 350 passed through bloody fighting on the Eastern Front in the uniform of the Czechoslovak Army. Many died at the first battle, at Sokolovo, where J. Haber and A. Bleiweiss were among those killed. Only 123 of them made it home, with 90 returning to Ostrava. The number of Jewish survivors from Těšín has not yet been calculated and very few of their stories have been processed in detail.

The transports to Nisko have been most notably studied by Czech historian Mečislav Borák, with his latest work on the subject the monograph The First Deportations of European Jews. Through interviews with survivors and research into NKVD documents, the ÚSTR historians Jan Dvořák and Adam Hradilek have also explored the subject; see the article The First Transports of European Jews in the History of the Holocaust or the publication Jews in the Gulag: Soviet labour and POW camps in WWII in the recollections of Jewish refugees from Czechoslovakia, from which we are publishing an excerpt: an interview with K. Borský. The harsh fates of the Jews deported to Nisko from Vienna (who, unlike Czech and Polish Jews, were not amnestied) have been analysed by Jan Dvořák in the stand-alone study Destination Nisko: The First Organised Deportation of Views from Vienna. Further information on the deportations to Nisko can be found, e.g., in a database prepared by Libuše and Michal Salomonovič and in Martin Šmok’s guide to the fates of Ostrava’s Jews on iWalks.