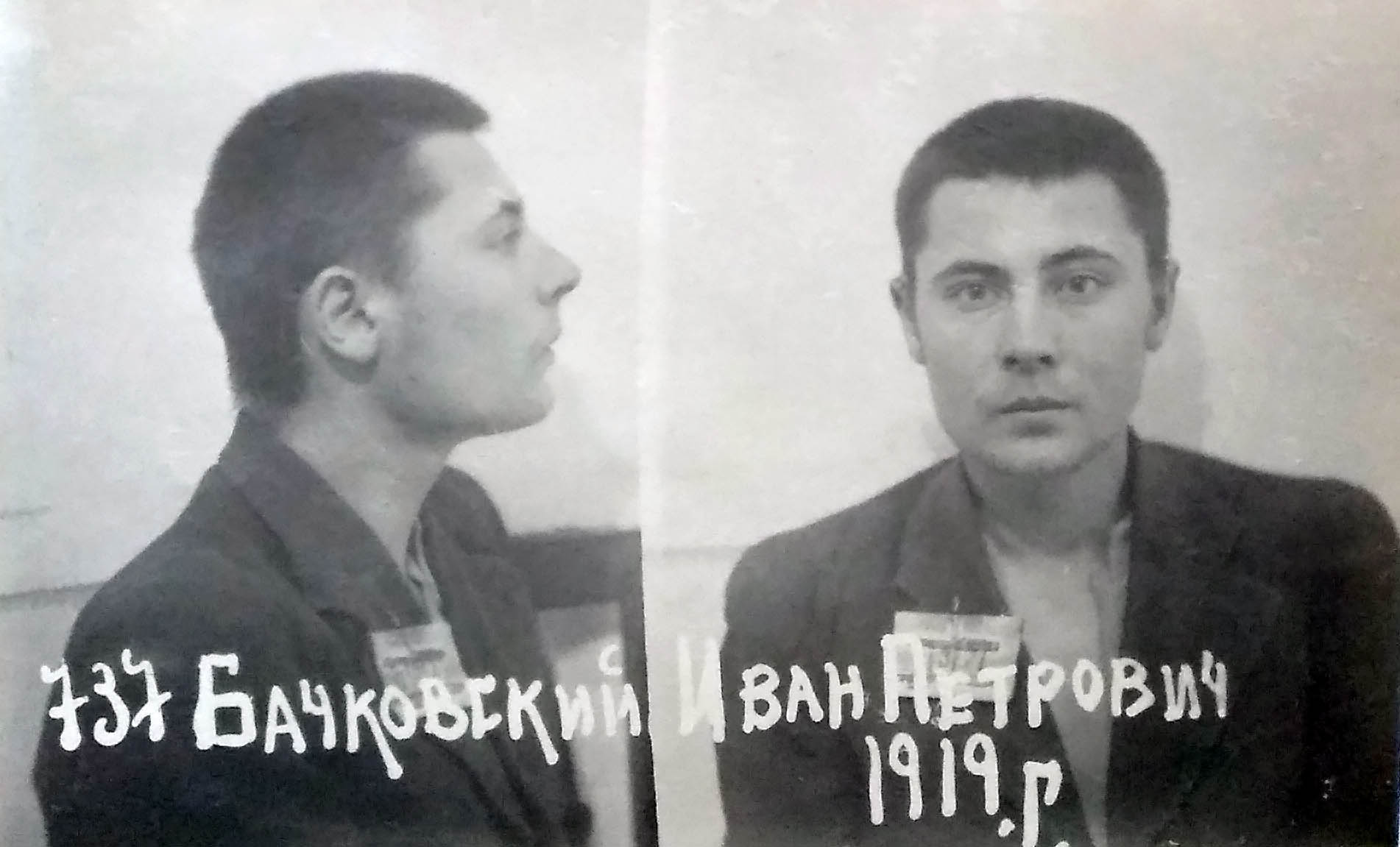

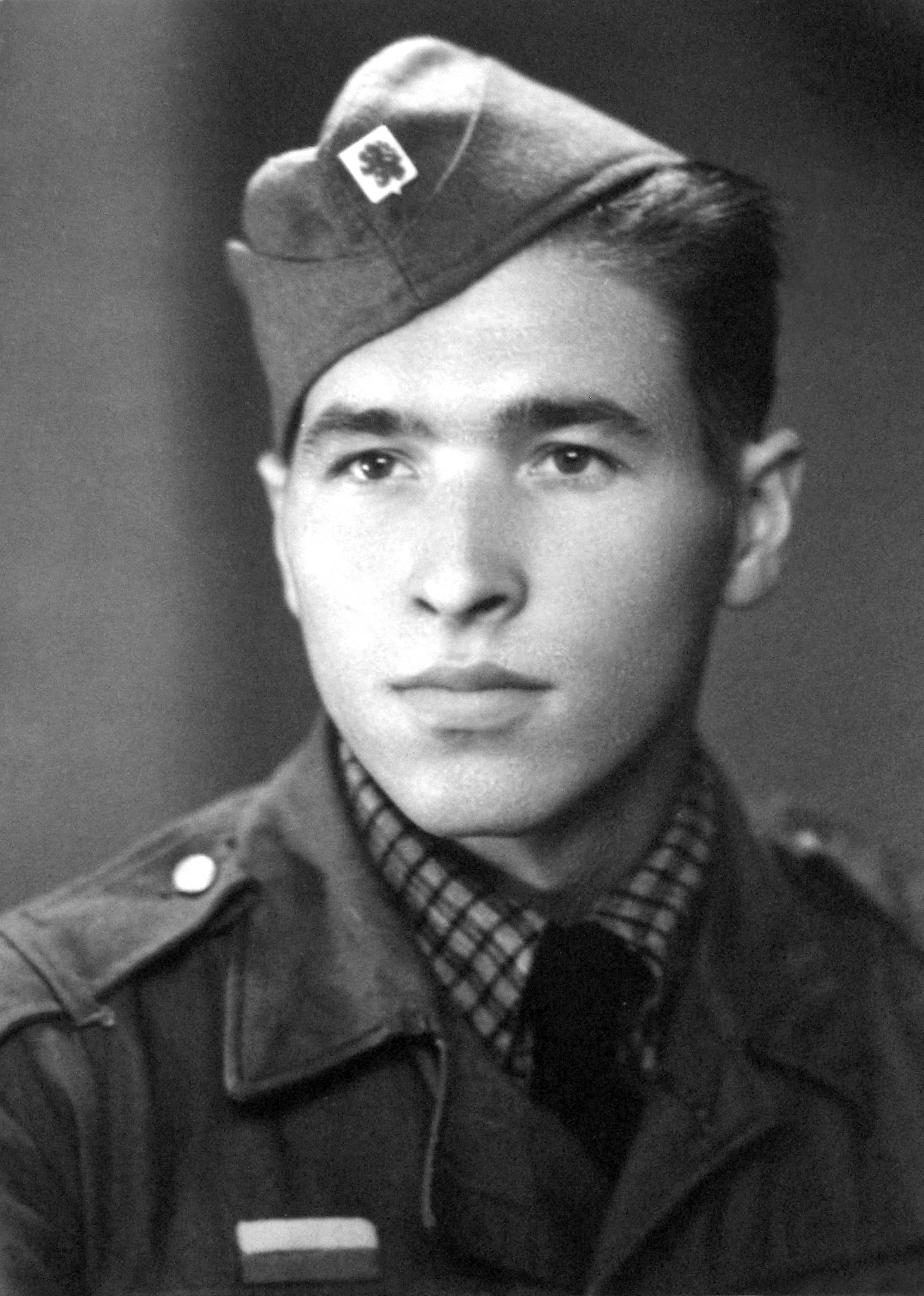

Jan Bačkovský (1919–2006)

Testimony. Manuscript in family archive

Excerpts from the memoir were published in the anthology Ozvěny gulagu. Povídky a vzpomínky (Echoes of the Gulag: Short Stories and Recollections) (compiled by Semjon Vilenskij, Lukáš Babka)

Imprisoned in years 1939–1942: Sambor, Voroshilovgrad, Starobilsk, Vorkutlag (camps nos. 8 and 9)

Jan Bačkovský was born into a farming family in the village of Štefurov in Eastern Czechoslovakia in 1919. He was active as a secondary school student in the local Communist organisation from the mid-1930s. Following the breakup of Czechoslovakia he decided to escape to the Soviet Union. As soon as he crossed the border he was arrested on 7 December 1939. He was subsequently imprisoned in Sambor, Voroshilovgrad and Starobilsk, where he was sentenced to five years forced labour and transported to Vorkutlag. He lived in camps nos. 8 and 9 and carried out lumberjack and excavation work. After a year and a half of debilitating labour accompanied by insufficient nutrition, he was made an office assistant, which helped him survive the camps. On 7 January 1942 he was released on the basis of a Soviet amnesty of some of the Czechoslovaks in the Gulag announced with a view to former prisoners being deployed against the Nazis in the war. Like many Czechoslovaks, therefore, Bačkovský joined a Czechoslovak military unit then being formed in Buzuluk. He took part in battles at Sokolovo, Kiev and Dukla and was injured twice. Bačkovský was a two-time recipient of the Czechoslovak War Cross 1939 for the battles at Kiev and Dukla and also received the Polish War Cross. He spent the first half of the 1950s at the Polish Military Academy in Warsaw. In the second half he headed the Military Department at the Teaching Hospital in Hradec Králové while also studying at the Military Academy in Brno. From the late 1950s until 1968 he served at the General Staff in Prague. Due to his rejection of the Soviet invasion and the normalisation policies of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia he was demoted and expelled from the party in autumn 1969. In the 1970s and 1980s he was a labourer in construction and was monitored by the StB. In the second half of the 1980s he wrote a memoir of his imprisonment in the USSR, which has been preserved in the family archive. Jan Bačkovský did not receive full rehabilitation until after 1989. In 1991 he was promoted to general major. He died in Prague in November 2006.

Jan Bačkovský was born into a farming family in the village of Štefurov in Eastern Czechoslovakia in 1919. He was active as a secondary school student in the local Communist organisation from the mid-1930s. Following the breakup of Czechoslovakia he decided to escape to the Soviet Union. As soon as he crossed the border he was arrested on 7 December 1939. He was subsequently imprisoned in Sambor, Voroshilovgrad and Starobilsk, where he was sentenced to five years forced labour and transported to Vorkutlag. He lived in camps nos. 8 and 9 and carried out lumberjack and excavation work. After a year and a half of debilitating labour accompanied by insufficient nutrition, he was made an office assistant, which helped him survive the camps. On 7 January 1942 he was released on the basis of a Soviet amnesty of some of the Czechoslovaks in the Gulag announced with a view to former prisoners being deployed against the Nazis in the war. Like many Czechoslovaks, therefore, Bačkovský joined a Czechoslovak military unit then being formed in Buzuluk. He took part in battles at Sokolovo, Kiev and Dukla and was injured twice. Bačkovský was a two-time recipient of the Czechoslovak War Cross 1939 for the battles at Kiev and Dukla and also received the Polish War Cross. He spent the first half of the 1950s at the Polish Military Academy in Warsaw. In the second half he headed the Military Department at the Teaching Hospital in Hradec Králové while also studying at the Military Academy in Brno. From the late 1950s until 1968 he served at the General Staff in Prague. Due to his rejection of the Soviet invasion and the normalisation policies of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia he was demoted and expelled from the party in autumn 1969. In the 1970s and 1980s he was a labourer in construction and was monitored by the StB. In the second half of the 1980s he wrote a memoir of his imprisonment in the USSR, which has been preserved in the family archive. Jan Bačkovský did not receive full rehabilitation until after 1989. In 1991 he was promoted to general major. He died in Prague in November 2006.

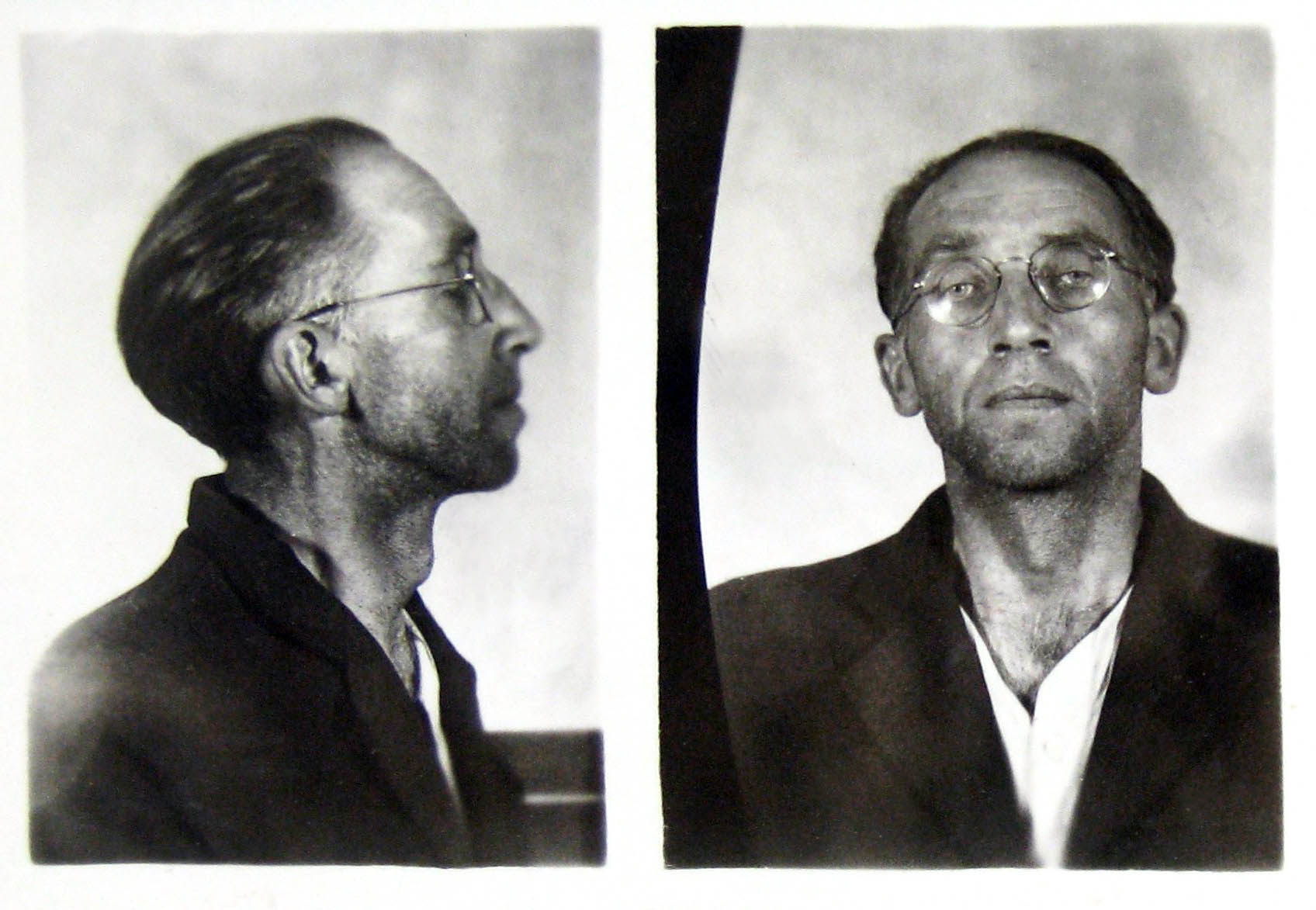

Jiří Bezděk (1907–1968)

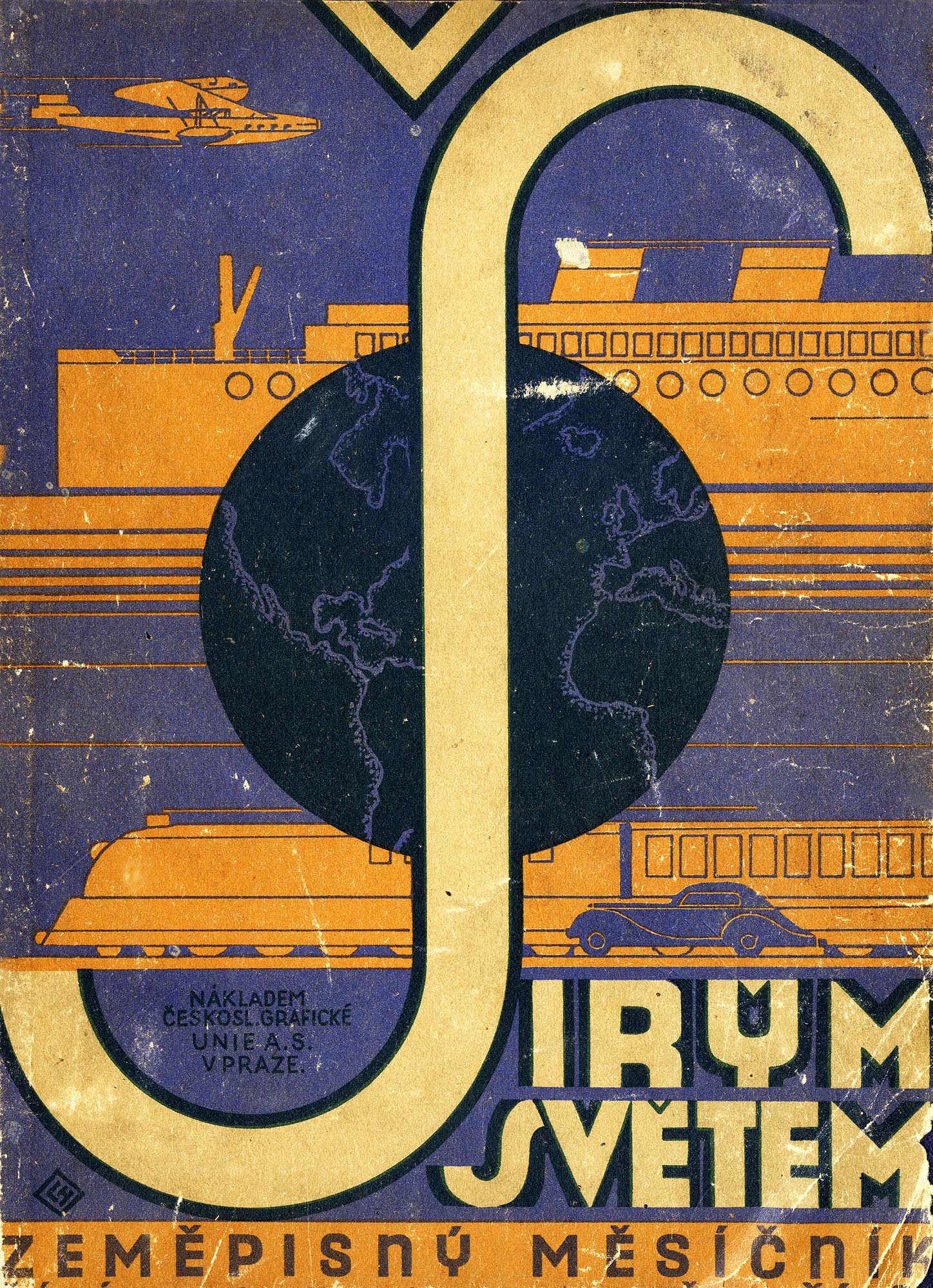

Ze Solověckých ostrovů do východní Sibiře a Domů ze sibiřského vyhnanství (From the Solovetsky Islands to Eastern Siberia and Home from Siberian Exile) – a memoir of internment and internal exile in the USSR published in instalments in the magazine Širým světem: Year 15, 1938, p. 267–273, 321–325, 379–382, 437–441, 510–514, 555–560; Year 16, 1939, p. 664–680

Imprisoned in 1930–1936: Yaroslavl, Solovetsky special camp, internal exile at the Selengino settlement

Jiří Bezděk was born in the village of Svébohov in 1907. After elementary school he made a living from casual labour. In 1925 he underwent two-year military service in Olomouc, at the same time completing a teaching course in Zábřeh. In October 1927 he took up a teaching post at a Czech school in the village of Vyšehrad in the Kiev Oblast. In 1928 he joined the Communist Party. He was arrested in July 1930 on a trip to Kiev. During a trial in Kharkov the Supreme Court of the USSR sentenced him to death under articles 54–6 and 54–11 of the country’s criminal code. Jiří Bezděk awaited the carrying out of the sentence in prison in Yaroslavl and from 1933 on the Solovetsky Islands. In 1935 his punishment was commuted to five years’ internment at a corrective labour camp and five years’ exile in the village of Selengino on the river Angara in Krasnoyarsk Oblast. It was there on 20 August 1936 that he received permission to travel to Czechoslovakia thanks to a Czechoslovak Ministry of Foreign Affairs initiative. Following his return in September 1936 he was employed until 1944 as a clerk at the State Statistics Office and published memoirs of his imprisonment and exile in the USSR in the magazine Širým světem and other periodicals. He also wrote several articles and reports on forgotten Czech fellow prisoners still being held behind barbed wire in Soviet labour camps. Under a decision from the Nazi authorities he was transferred to the Prison Education Service on 1 August 1944. His main task was to deliver lectures on his experiences and real conditions in the USSR to the Protectorate working class. Bezděk remained in the post until the liberation of Czechoslovakia on 29 May 1945. He was arrested on suspicion of collaborating with the Nazi regime but was released in October 1945 and criminal proceedings against him were halted. At that time Bezděk was working as a teacher at a vocational school linked to the Pluto mine in Louka by Litvínov. At the end of 1946 he was appointed head of education of trainee miners at the North Bohemian Mines in Most. In 1950 he was made a trade union leader overseeing worker recruitment. In June 1951 he was dismissed for political reasons, subsequently taking a job as an auxiliary labourer at the Průmstav enterprise in Most. Half a year later, on 28 January 1952, Bezděk was arrested. In November 1953 he was sentenced to 18 years in jail in one of a number of trials of managers at nationalised mines and leading mining experts. He got out under a presidential amnesty in May 1960. After his release he lived in Jablonec nad Nisou, where he worked in a costume jewellery factory at the SVED cooperative. Jiří Bezděk died at a sanatorium in Křemýž near Teplice on 16 September 1968.

Jiří Bezděk was born in the village of Svébohov in 1907. After elementary school he made a living from casual labour. In 1925 he underwent two-year military service in Olomouc, at the same time completing a teaching course in Zábřeh. In October 1927 he took up a teaching post at a Czech school in the village of Vyšehrad in the Kiev Oblast. In 1928 he joined the Communist Party. He was arrested in July 1930 on a trip to Kiev. During a trial in Kharkov the Supreme Court of the USSR sentenced him to death under articles 54–6 and 54–11 of the country’s criminal code. Jiří Bezděk awaited the carrying out of the sentence in prison in Yaroslavl and from 1933 on the Solovetsky Islands. In 1935 his punishment was commuted to five years’ internment at a corrective labour camp and five years’ exile in the village of Selengino on the river Angara in Krasnoyarsk Oblast. It was there on 20 August 1936 that he received permission to travel to Czechoslovakia thanks to a Czechoslovak Ministry of Foreign Affairs initiative. Following his return in September 1936 he was employed until 1944 as a clerk at the State Statistics Office and published memoirs of his imprisonment and exile in the USSR in the magazine Širým světem and other periodicals. He also wrote several articles and reports on forgotten Czech fellow prisoners still being held behind barbed wire in Soviet labour camps. Under a decision from the Nazi authorities he was transferred to the Prison Education Service on 1 August 1944. His main task was to deliver lectures on his experiences and real conditions in the USSR to the Protectorate working class. Bezděk remained in the post until the liberation of Czechoslovakia on 29 May 1945. He was arrested on suspicion of collaborating with the Nazi regime but was released in October 1945 and criminal proceedings against him were halted. At that time Bezděk was working as a teacher at a vocational school linked to the Pluto mine in Louka by Litvínov. At the end of 1946 he was appointed head of education of trainee miners at the North Bohemian Mines in Most. In 1950 he was made a trade union leader overseeing worker recruitment. In June 1951 he was dismissed for political reasons, subsequently taking a job as an auxiliary labourer at the Průmstav enterprise in Most. Half a year later, on 28 January 1952, Bezděk was arrested. In November 1953 he was sentenced to 18 years in jail in one of a number of trials of managers at nationalised mines and leading mining experts. He got out under a presidential amnesty in May 1960. After his release he lived in Jablonec nad Nisou, where he worked in a costume jewellery factory at the SVED cooperative. Jiří Bezděk died at a sanatorium in Křemýž near Teplice on 16 September 1968.

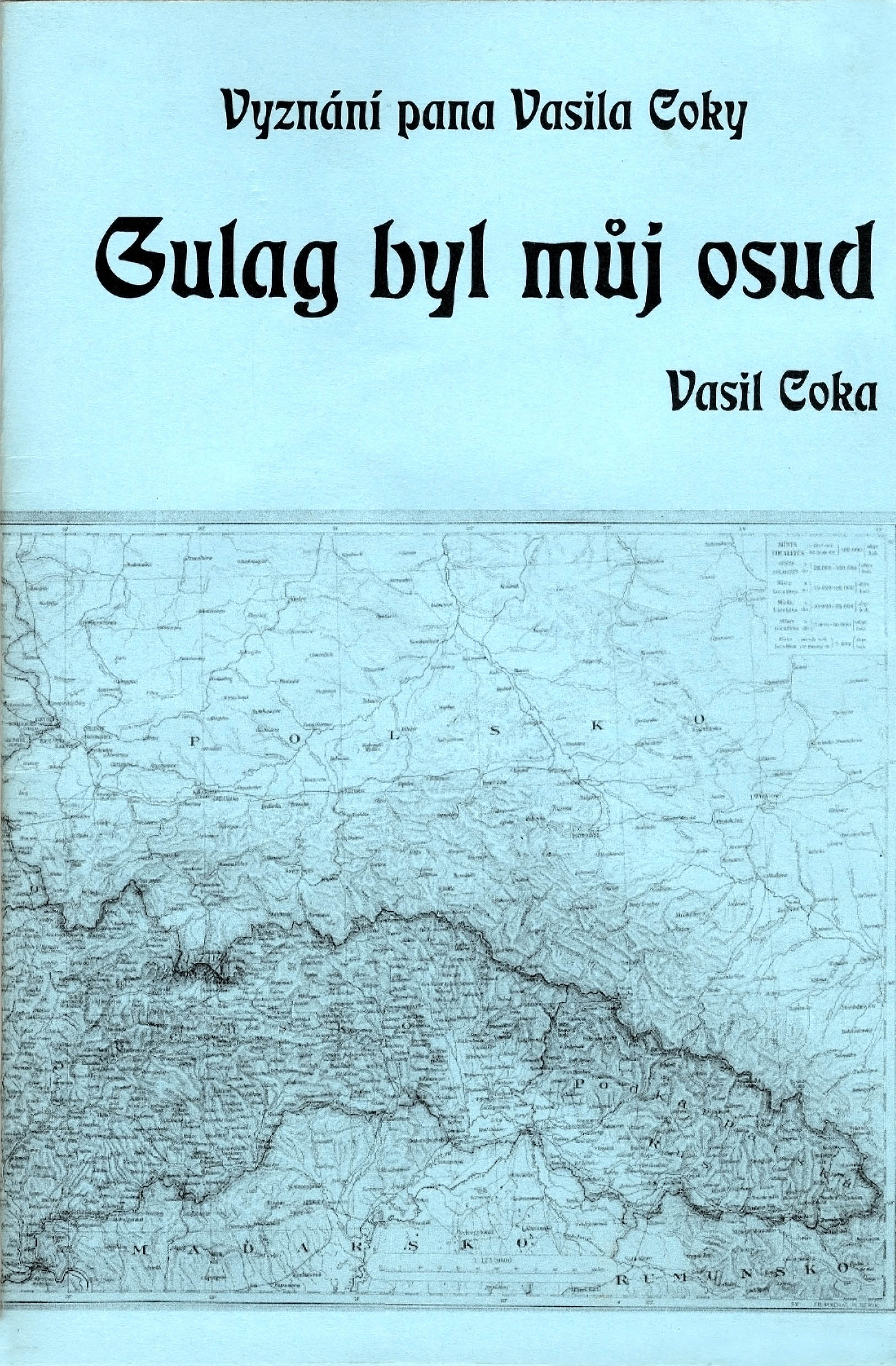

Vasil Coka (1923–2015)

Gulag byl můj osud (The Gulag Was My Fate). Město Příbor, 2006

Imprisoned 1939–1942: Nadvirna, Stanislavov, Romny, Ukhtizhemlag

Vasil Coka was born in the village of Dulovo in Carpathian Ruthenia on 18 April 1923. In 1927 the family moved to France, where his father had already been working for some years. In Paris he did very well during six years of schooling. In 1935 his mother and the children returned to Carpathian Ruthenia, where Vasil attended grammar school in Khust. Following the Hungarian occupation in March 1939 he was barred from studying further and threatened with forced membership of the Levente Hungarian military youth groups. He and a classmate decided to escape to the Soviet Union with a view to continuing their studies. They crossed the border on 5 June 1940 and were immediately arrested in the village of Rafajov by a Soviet border patrol, undergoing interrogation for the first time at nearby station. Roughly two weeks later they were escorted to a prison in Nadvirna. After two months there they were sent to Stanislavov and finally to a transit camp in Romny, where Coka was sentenced to three years forced labour for illegally crossing the border. He was then sent on a cattle wagon to Kotlas, from where he continued along the River Pechora in the northeastern part of European Russia, where the prisoners first had to build a labour camp. Soon afterward Coka was sent to another camp near Ukhta, where he worked in forestry and digging gas pipelines. After some time he became so weak that he remained in the camp zone. He thus met a Chinese cook who gave him bigger soup and bread portions in exchange for his assistance. He shared his food with a brigadier who assigned him to light work, crucial for surviving the camps. An amnesty for Czechoslovaks also concerned Coka. He reported to the military unit in Buzuluk on 17 February 1943 and following basic training underwent officer training. He subsequently took part in battles for Kiev, Bila Cerkva and Ruda and did a five-month course for infantry officers in Luck. In early 1945 he served as an instructor with a nascent Czechoslovak independent brigade in the USSR, with which as platoon commander he took part in battles in western Slovakia and eastern Moravia. In May 1945 he was shot in the lungs and stomach at Bystřice pod Hostýnem. After a protracted recovery he worked at the Military Invalids Hospital in Prague’s Jenerálka district. He applied to the Military Academy in Hranice but was rejected on account of persistent medical problems; in June 1947 he was discharged for the same reason. He moved to Krnov where as a participant in the “second resistance” he was assigned a newsagents. In subsequent years he was questioned by the Krnov State Security as part of an investigation of “illegal organisations”, suspected of smuggling people across the border. As a consequence he was demoted in February 1949 from lieutenant to soldier in reserve; in 1964 he was rehabilitated and promoted to captain in reserve. Following the nationalisation of the newsagents in 1950 he became a forestry worker. In 1953 he entered Krnov’s Kovoslužba factory, where in 1958 he joined the Communist Party. Until his retirement he held management positions at several restaurants and hotels in northern Moravia and Silesia. In 1971 he was expelled from the Communist Party for disapproving of the Soviet occupation. Vasil Coka died on 9 January 2015.

Vasil Coka was born in the village of Dulovo in Carpathian Ruthenia on 18 April 1923. In 1927 the family moved to France, where his father had already been working for some years. In Paris he did very well during six years of schooling. In 1935 his mother and the children returned to Carpathian Ruthenia, where Vasil attended grammar school in Khust. Following the Hungarian occupation in March 1939 he was barred from studying further and threatened with forced membership of the Levente Hungarian military youth groups. He and a classmate decided to escape to the Soviet Union with a view to continuing their studies. They crossed the border on 5 June 1940 and were immediately arrested in the village of Rafajov by a Soviet border patrol, undergoing interrogation for the first time at nearby station. Roughly two weeks later they were escorted to a prison in Nadvirna. After two months there they were sent to Stanislavov and finally to a transit camp in Romny, where Coka was sentenced to three years forced labour for illegally crossing the border. He was then sent on a cattle wagon to Kotlas, from where he continued along the River Pechora in the northeastern part of European Russia, where the prisoners first had to build a labour camp. Soon afterward Coka was sent to another camp near Ukhta, where he worked in forestry and digging gas pipelines. After some time he became so weak that he remained in the camp zone. He thus met a Chinese cook who gave him bigger soup and bread portions in exchange for his assistance. He shared his food with a brigadier who assigned him to light work, crucial for surviving the camps. An amnesty for Czechoslovaks also concerned Coka. He reported to the military unit in Buzuluk on 17 February 1943 and following basic training underwent officer training. He subsequently took part in battles for Kiev, Bila Cerkva and Ruda and did a five-month course for infantry officers in Luck. In early 1945 he served as an instructor with a nascent Czechoslovak independent brigade in the USSR, with which as platoon commander he took part in battles in western Slovakia and eastern Moravia. In May 1945 he was shot in the lungs and stomach at Bystřice pod Hostýnem. After a protracted recovery he worked at the Military Invalids Hospital in Prague’s Jenerálka district. He applied to the Military Academy in Hranice but was rejected on account of persistent medical problems; in June 1947 he was discharged for the same reason. He moved to Krnov where as a participant in the “second resistance” he was assigned a newsagents. In subsequent years he was questioned by the Krnov State Security as part of an investigation of “illegal organisations”, suspected of smuggling people across the border. As a consequence he was demoted in February 1949 from lieutenant to soldier in reserve; in 1964 he was rehabilitated and promoted to captain in reserve. Following the nationalisation of the newsagents in 1950 he became a forestry worker. In 1953 he entered Krnov’s Kovoslužba factory, where in 1958 he joined the Communist Party. Until his retirement he held management positions at several restaurants and hotels in northern Moravia and Silesia. In 1971 he was expelled from the Communist Party for disapproving of the Soviet occupation. Vasil Coka died on 9 January 2015.

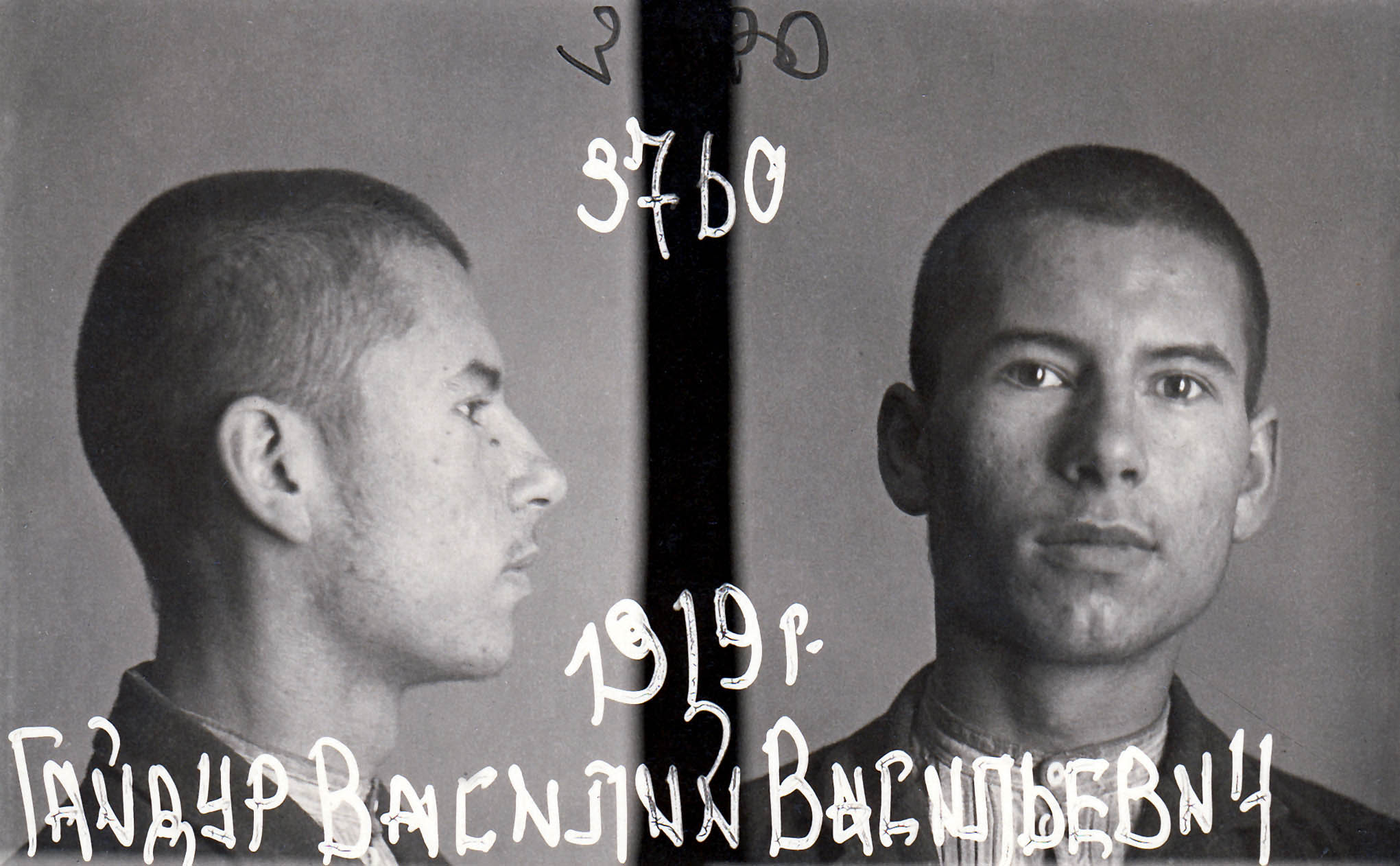

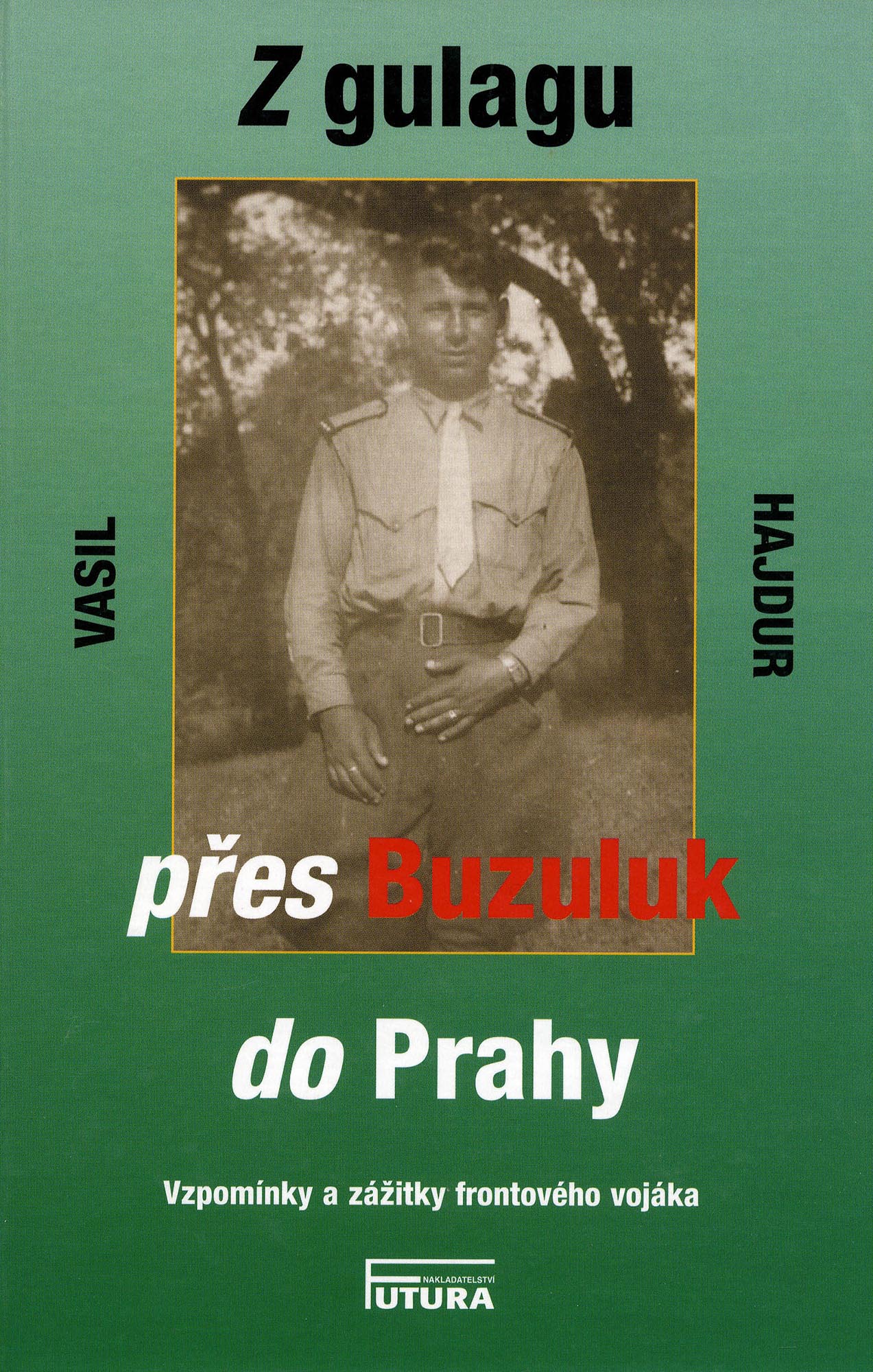

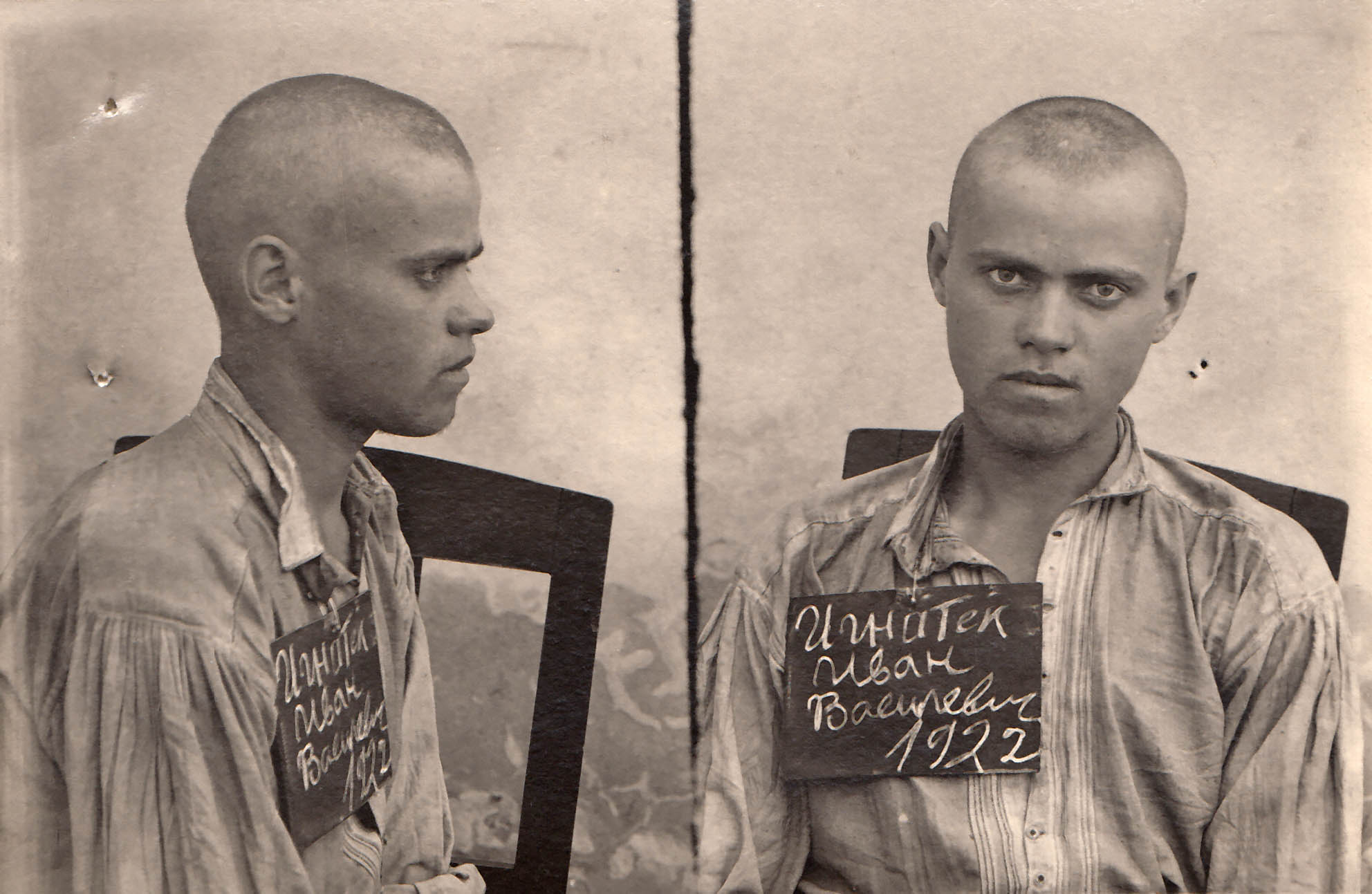

Vasil Hajdur (1919–2015)

Z gulagu přes Buzuluk do Prahy (From the Gulag via Buzuluk to Prague). Futura, 2011

Imprisoned in 1940–1942: Nadvirna, Poltava, Kharkov, Ivdellag

Vasil Hajdur was born in the village of Nižní Seliště near Khust in Carpathian Ruthenia on 24 June 1919. His father was a carpenter and ran a smallholding with his mother. After finishing general school young Vasil repaired local roads to make some money and helped his parents on the farm. He lived that way until 1940, when he was meant to enter the Hungarian army. Following Hungary’s occupation of part of Carpathian Ruthenia in March 1939 conscription gradually came to apply to all Ruthenians of legal age. Therefore in summer 1940 Hajdur and four friends also facing the draft decided to flee to the USSR. However, as soon as they crossed the Hungarian-Soviet border on 15 July 1940 they were picked up by a Soviet patrol. They were initially imprisoned in Nadvirna, where they also underwent their first interrogations. After three months Hajdur was transferred to a larger prison in Poltava. There in October 1940 he was sentenced to three years in corrective labour camps for illegally crossing the border. Due to health problems he could not be deported immediately, thus avoiding a transport to the distant Kolyma. After recovering he was moved to a prison in Kharkov, where in December 1940 he was sent to the Talica labour camp (part of Ivdellag) near Sverdlovsk (today Yekaterinburg) in the central Urals. Prisoners there mainly worked in forestry, felling trees and processing the woods, or at the local brickworks. Hajdur spent almost two years at this labour camp. He was released at the end of 1942, almost a year after the Soviet government had declared an amnesty for imprisoned Czechoslovak citizens, who entered a Czechoslovak military unit then being set up in Buzuluk. Hajdur signed up on 10 January 1943 and after brief training was assigned to the 3rd Platoon of the 2nd Infantry Company. By March 1943 he had taken part in the Czechoslovak battalion’s first deployment in the battle of Sokolovo. He also fought at Kiev, Bila Tserkva and elsewhere, suffering two injuries in the Dukla operation in September 1944. Following convalescence he was assigned to the 2nd Artillery Regiment and took part in the liberation of Slovakia and Moravia. The war ended for him in Kroměříž in May 1945. After the war he supplemented his education with a one-year course at a grammar school in Prague and in 1946 entered the Military Academy in Hranice. He served in the Czechoslovak Army until his retirement. Vasil Hajdur died in Tabor on 2 September 2015.

Vasil Hajdur was born in the village of Nižní Seliště near Khust in Carpathian Ruthenia on 24 June 1919. His father was a carpenter and ran a smallholding with his mother. After finishing general school young Vasil repaired local roads to make some money and helped his parents on the farm. He lived that way until 1940, when he was meant to enter the Hungarian army. Following Hungary’s occupation of part of Carpathian Ruthenia in March 1939 conscription gradually came to apply to all Ruthenians of legal age. Therefore in summer 1940 Hajdur and four friends also facing the draft decided to flee to the USSR. However, as soon as they crossed the Hungarian-Soviet border on 15 July 1940 they were picked up by a Soviet patrol. They were initially imprisoned in Nadvirna, where they also underwent their first interrogations. After three months Hajdur was transferred to a larger prison in Poltava. There in October 1940 he was sentenced to three years in corrective labour camps for illegally crossing the border. Due to health problems he could not be deported immediately, thus avoiding a transport to the distant Kolyma. After recovering he was moved to a prison in Kharkov, where in December 1940 he was sent to the Talica labour camp (part of Ivdellag) near Sverdlovsk (today Yekaterinburg) in the central Urals. Prisoners there mainly worked in forestry, felling trees and processing the woods, or at the local brickworks. Hajdur spent almost two years at this labour camp. He was released at the end of 1942, almost a year after the Soviet government had declared an amnesty for imprisoned Czechoslovak citizens, who entered a Czechoslovak military unit then being set up in Buzuluk. Hajdur signed up on 10 January 1943 and after brief training was assigned to the 3rd Platoon of the 2nd Infantry Company. By March 1943 he had taken part in the Czechoslovak battalion’s first deployment in the battle of Sokolovo. He also fought at Kiev, Bila Tserkva and elsewhere, suffering two injuries in the Dukla operation in September 1944. Following convalescence he was assigned to the 2nd Artillery Regiment and took part in the liberation of Slovakia and Moravia. The war ended for him in Kroměříž in May 1945. After the war he supplemented his education with a one-year course at a grammar school in Prague and in 1946 entered the Military Academy in Hranice. He served in the Czechoslovak Army until his retirement. Vasil Hajdur died in Tabor on 2 September 2015.

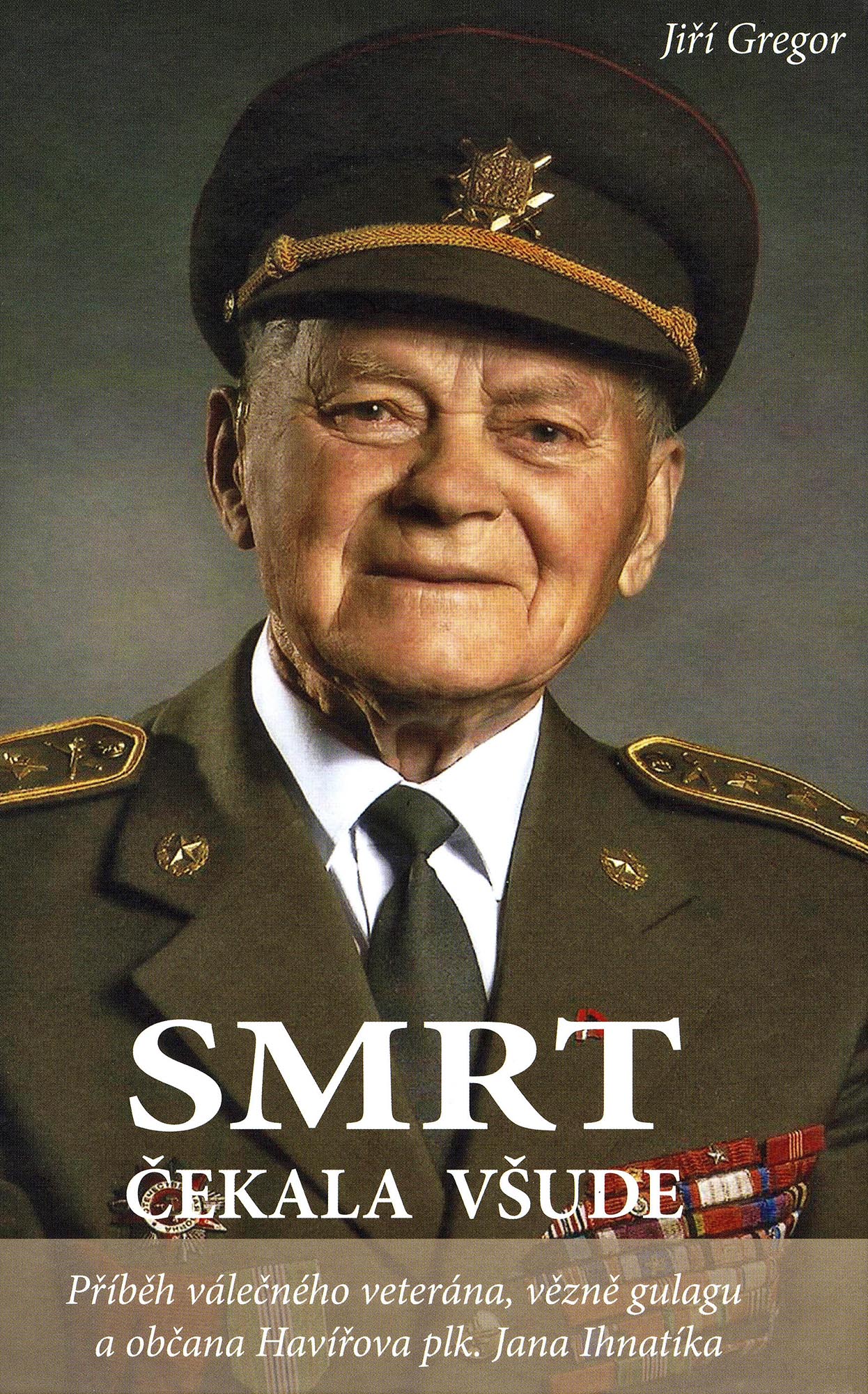

Jan Ihnatík (*1922)

Smrt čekala všude (Death Was Waiting Everywhere). Město Havířov, 2019

Imprisoned in 1940–1943: Skole, Stryi, Uman, Starobilsk, Uchtizhemlag

Jan Ihnatík was born in the Carpathian Ruthenian village of Poroškovo on 1 March 1922. After completing general school he did two years at a construction-focused secondary school in the village of Tuří Remety while also helping his parents on their smallholding. When Hungary occupied the remaining part of Carpathian Ruthenia in March 1939 he, like his peers, was faced with having to undergo compulsory training in Levente, the Hungarian paramilitary youth organisation. Influenced by local Communists and their reports of a “Soviet paradise on earth”, and with conscription into the Hungarian Army hanging over him, he decided with two friends to escape to the USSR. They crossed the border in early May 1940. Soon afterwards they were arrested by Soviet border guards and placed in an assembly camp in Skole already crowded with several dozen refugees. The provisional camp did not have the capacity for so many people so a large number of them were transferred to a prison in Stryi, where the main interrogations took place. They were later deported via a prison in Uman to Starobilsk, where in “quick trials” they received custodial sentences. Jan Ihnatík got the standard three years in corrective labour camps for illegally crossing the border. In early 1941 he and other convicts were sent to a labour camp near the city of Ukhta. There they constructed basic camp buildings, felled trees in the surrounding forests, helped with haymaking, etc. After some months the majority of Poles and Ruthenians were sent to remote labour camps in northern Russia. Ihnatík was fortunate. He had got to know the camp doctor, who helped him feign an injury and thus avoid the dreaded transport. In addition, the camp leadership assigned him to an assistant’s post at a nearby vocational crafts centre, where he received relatively large portions of food, a key condition for survival. He remained in that advantageous position until the start of 1943. He signed up to the Czechoslovak military unit in Buzuluk on 13 February 1943. Following basic training he attended a non-commissioned officers school and later an artillery school in Irbit. In the further course of the war he took part as an artillery platoon officer in the Czechoslovak army corps’ complete campaign in the USSR as well as the liberation of Czechoslovakia. He was injured in battle several times. After the war he remained in the army until his retirement, serving at a number of military units, mainly in Moravia. In 2019 he was still active chairman of the Czechoslovak Legionnaires Club in Havířov.

Jan Ihnatík was born in the Carpathian Ruthenian village of Poroškovo on 1 March 1922. After completing general school he did two years at a construction-focused secondary school in the village of Tuří Remety while also helping his parents on their smallholding. When Hungary occupied the remaining part of Carpathian Ruthenia in March 1939 he, like his peers, was faced with having to undergo compulsory training in Levente, the Hungarian paramilitary youth organisation. Influenced by local Communists and their reports of a “Soviet paradise on earth”, and with conscription into the Hungarian Army hanging over him, he decided with two friends to escape to the USSR. They crossed the border in early May 1940. Soon afterwards they were arrested by Soviet border guards and placed in an assembly camp in Skole already crowded with several dozen refugees. The provisional camp did not have the capacity for so many people so a large number of them were transferred to a prison in Stryi, where the main interrogations took place. They were later deported via a prison in Uman to Starobilsk, where in “quick trials” they received custodial sentences. Jan Ihnatík got the standard three years in corrective labour camps for illegally crossing the border. In early 1941 he and other convicts were sent to a labour camp near the city of Ukhta. There they constructed basic camp buildings, felled trees in the surrounding forests, helped with haymaking, etc. After some months the majority of Poles and Ruthenians were sent to remote labour camps in northern Russia. Ihnatík was fortunate. He had got to know the camp doctor, who helped him feign an injury and thus avoid the dreaded transport. In addition, the camp leadership assigned him to an assistant’s post at a nearby vocational crafts centre, where he received relatively large portions of food, a key condition for survival. He remained in that advantageous position until the start of 1943. He signed up to the Czechoslovak military unit in Buzuluk on 13 February 1943. Following basic training he attended a non-commissioned officers school and later an artillery school in Irbit. In the further course of the war he took part as an artillery platoon officer in the Czechoslovak army corps’ complete campaign in the USSR as well as the liberation of Czechoslovakia. He was injured in battle several times. After the war he remained in the army until his retirement, serving at a number of military units, mainly in Moravia. In 2019 he was still active chairman of the Czechoslovak Legionnaires Club in Havířov.

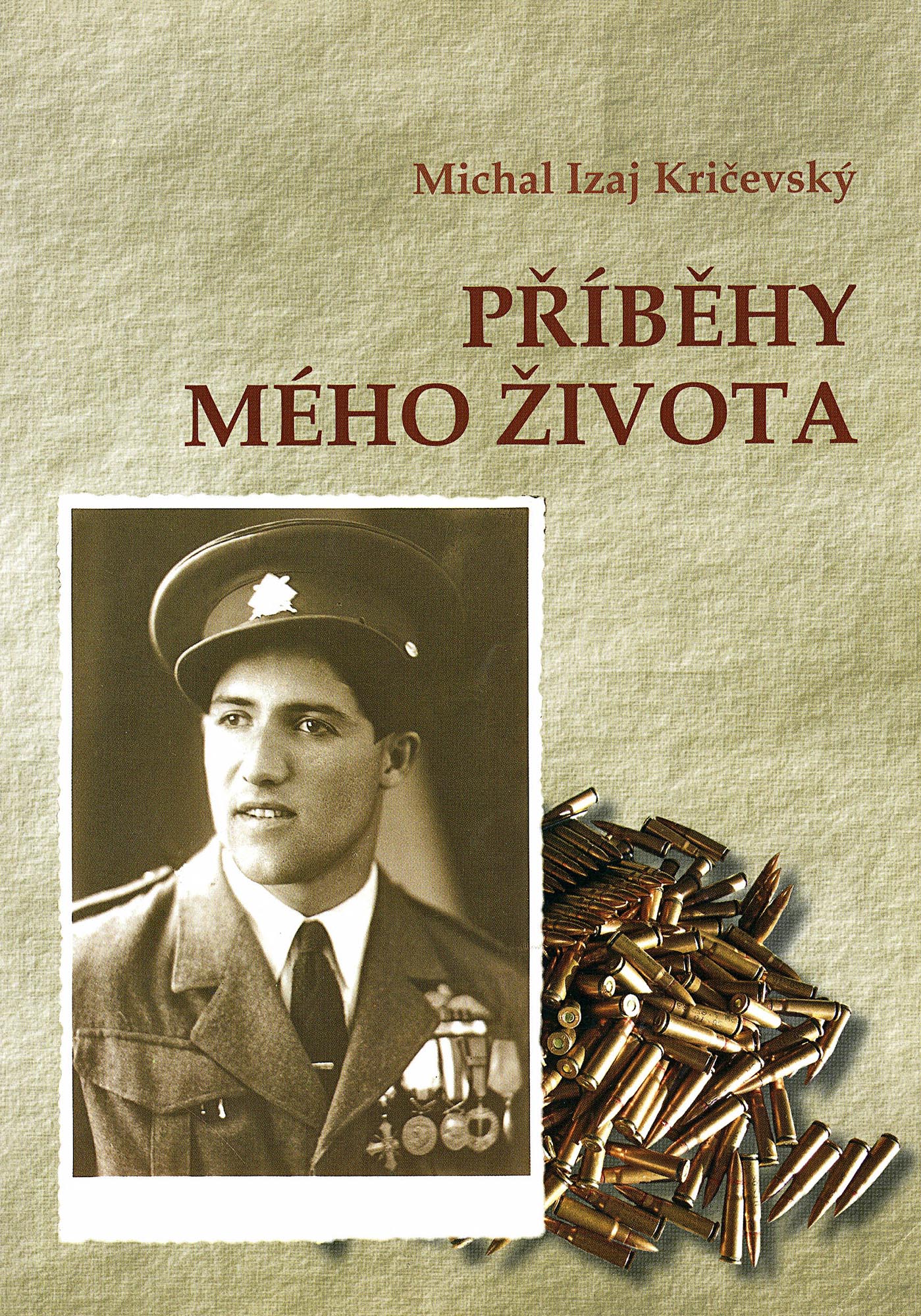

Michal Izaj (1921–2013)

Příběhy mého života (The Stories of My Life). Československá obec legionářská, 2011

Imprisoned in 1940–1943: Nadvirna, Stanislavov, Lviv, Kiev, Kharkov, Intinlag

Michal Izaj was born in Kričev in Carpathian Ruthenia on 12 December 1921. He attended general school in Khust and later did manual labour and firearms repairs to earn a living alongside helping on the family farm. In the wake of the Hungarian occupation of Carpathian Ruthenia in March 1939 he was forced to join the Hungarian paramilitary youth organisation Levente. However, he only took part in three exercises before, along with seven other Ruthenians, fleeing to Polish territory at that time occupied by the Soviet Union. The refugees made for Krakow, where they planned to sign up with a Czech and Slovak legion. However, they were arrested by the NKVD in the city of Vorokhta. This was followed by interrogations and transfer to Rafajlov, where the Soviets gathered arrested Ruthenian refugees. After around a week border guards took them to the frontier, saying they were to return home. Izaj hid with relatives in his native village from the Hungarians. Alongside punishment for desertion of Levente he now faced Hungarian police persecution over his earlier weapons repairs. Therefore after some time he again contacted Ruthenians planning to escape to the USSR and in late June 1940 crossed the border one more time. The group were again detained by a Soviet border patrol and taken to a prison in Nadvirna. After a number of weeks the refugees ended up in Stanislavov, where on 10 February 1940 Izaj got three years in the labour camps for illegally crossing the border. Along with other convicts he was sent to a prison in Lviv and then on to Kiev and Kharkov. From there they continued on to Kotlas and then by train, boat and foot to Kozhva. Izaj’s group worked in the Kedrovyy Shor selchozlag (agricultural camp) by the river Pechora, which was administered by Intinlag. Izaj was released from the camp after almost a year following an amnesty for Czechoslovak citizens. On 4 January 1943 he set off for the Czechoslovak military unit in Buzuluk, where he signed up on 24 January 1943. He underwent training in Novokhopyorsk and was first deployed in fighting at Kiev and Bila Tserka. He was seriously injured in the advance on Dukla and following convalescence did not take part in further battles. In early April 1945 he briefly served as the personal bodyguard of President Edvard Beneš during a stay in Košice. After the war he joined the National Security Corps and settled at Kněževes in central Bohemia. In the 1960s he took an early invalid’s pension. Michal Izaj died on 28 May 2013.

Michal Izaj was born in Kričev in Carpathian Ruthenia on 12 December 1921. He attended general school in Khust and later did manual labour and firearms repairs to earn a living alongside helping on the family farm. In the wake of the Hungarian occupation of Carpathian Ruthenia in March 1939 he was forced to join the Hungarian paramilitary youth organisation Levente. However, he only took part in three exercises before, along with seven other Ruthenians, fleeing to Polish territory at that time occupied by the Soviet Union. The refugees made for Krakow, where they planned to sign up with a Czech and Slovak legion. However, they were arrested by the NKVD in the city of Vorokhta. This was followed by interrogations and transfer to Rafajlov, where the Soviets gathered arrested Ruthenian refugees. After around a week border guards took them to the frontier, saying they were to return home. Izaj hid with relatives in his native village from the Hungarians. Alongside punishment for desertion of Levente he now faced Hungarian police persecution over his earlier weapons repairs. Therefore after some time he again contacted Ruthenians planning to escape to the USSR and in late June 1940 crossed the border one more time. The group were again detained by a Soviet border patrol and taken to a prison in Nadvirna. After a number of weeks the refugees ended up in Stanislavov, where on 10 February 1940 Izaj got three years in the labour camps for illegally crossing the border. Along with other convicts he was sent to a prison in Lviv and then on to Kiev and Kharkov. From there they continued on to Kotlas and then by train, boat and foot to Kozhva. Izaj’s group worked in the Kedrovyy Shor selchozlag (agricultural camp) by the river Pechora, which was administered by Intinlag. Izaj was released from the camp after almost a year following an amnesty for Czechoslovak citizens. On 4 January 1943 he set off for the Czechoslovak military unit in Buzuluk, where he signed up on 24 January 1943. He underwent training in Novokhopyorsk and was first deployed in fighting at Kiev and Bila Tserka. He was seriously injured in the advance on Dukla and following convalescence did not take part in further battles. In early April 1945 he briefly served as the personal bodyguard of President Edvard Beneš during a stay in Košice. After the war he joined the National Security Corps and settled at Kněževes in central Bohemia. In the 1960s he took an early invalid’s pension. Michal Izaj died on 28 May 2013.

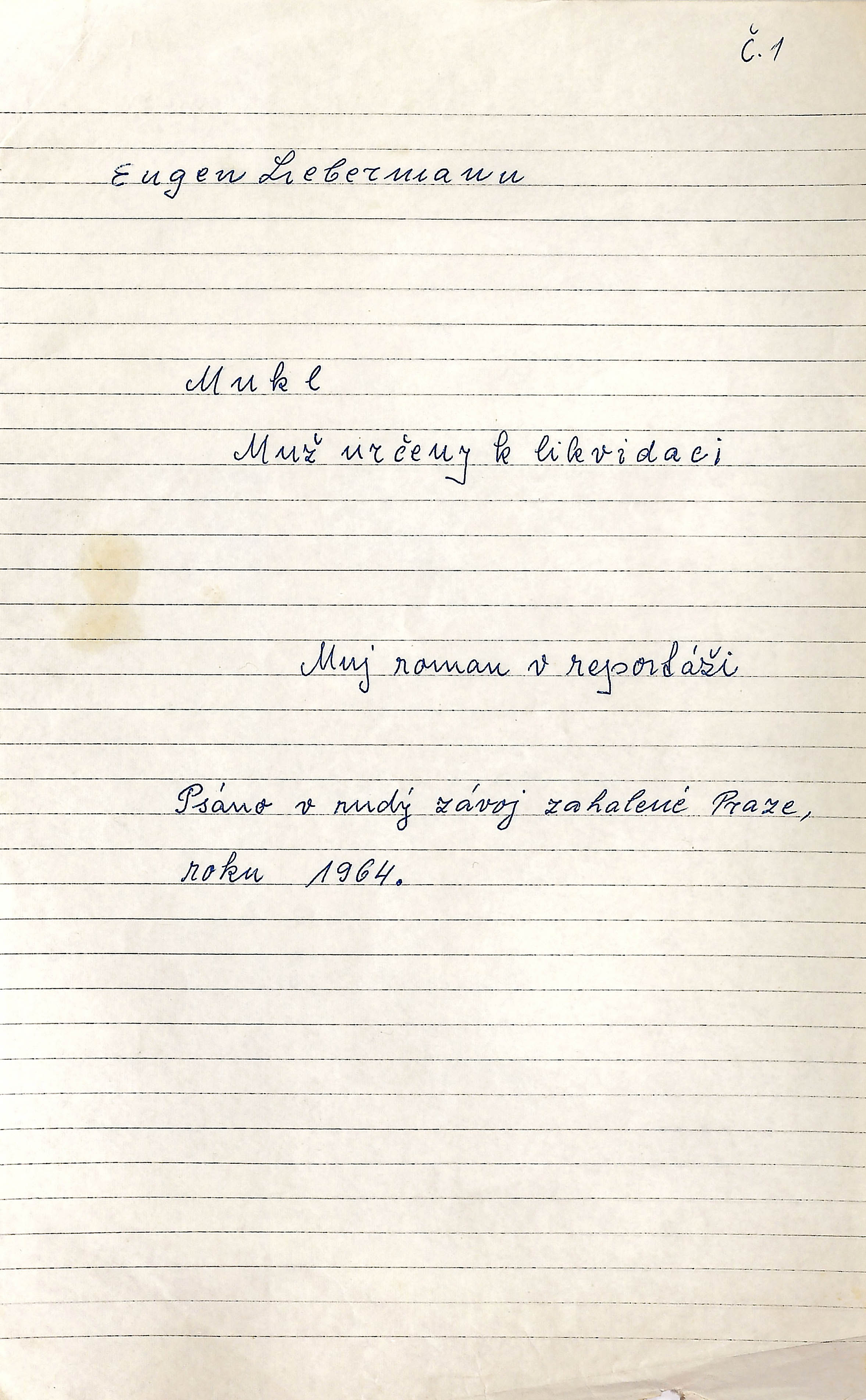

Evžen Lieberman (*1922)

MUKL – muž určený k likvidaci (Man Intended for Liquidation). Memoir manuscript in Institute for Study of Totalitarian Regimes archive

Imprisoned in 1946–1948: Uzhhorod, Uchtizhemlag

Evžen Lieberman was born into a Jewish trading family in the village of Sjurte in Carapthian Ruthenia in 1922. He and his brother Herman were abducted to a

Hungarian labour camp in 1943. This saved their lives – the rest of the family died in Nazi concentration camps. Following liberation Lieberman moved to Uzzhorod

and in April 1946 married Elizaveta Šumbergerová, one of the few to return from Auschwitz. He managed to take up the option of Czechoslovak citizenship in 1945 but

that choice was not open to his wife. They therefore decided to illegally leave the then Soviet Carpathian Ukraine for relatives in Satu Mare, Romania, from where

they hoped to continue on to Czechoslovakia. The Liebermans’ friend from Sjurte, cobbler Arpád Elkovič (born 1908), and his wife Olg Elkovič (1927),

who had survived the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, decided to join them in their escape. On the night of 27 October 1946 the two couples were arrested by Soviet

border guards, about 80 metres from the Romanian border near the village of Černa, and handed over to the NKVD. They released Elizaveta after several months as she

was pregnant. Evžen Lieberman was charged with organising a group border crossing. A year later, on Christmas Eve 1947, he was sentenced to three years in jail by

a military tribunal in Uzzhorod. He served that time in Gulag camps around the northern city of Ukhta in the Komi Republic. His friend Arpád Elkovič also got forced

labour but never returned from the Soviet camps. Evžen Lieberman was eventually released and was first sent to Poland, where with the help of the American Jewish Joint

Distribution Committee (JOINT) he illegally crossed into Czechoslovakia. There he legalised his stay and was reunited with his wife and the son he had never known.

In Czechoslovakia Lieberman became involved in Jewish Community and JOINT underground activities. This mainly comprised the smuggling of Jewish refugees from central

European Communist states to Austria, from where they continued to Palestine. His brother Herman was also active in this endeavour. When they were discovered Herman was

tortured to death in investigative custody at Prague’s Ruznyě prison. Evžen Lieberman got a seven-year jail term. Following his release in 1965 he was permitted to travel

to Israel with his son. Before his departure he wrote his memoirs, the handwritten manuscript MUKL – muž určený k likvidaci (Man Intended for Liquidation)..

Evžen Lieberman was born into a Jewish trading family in the village of Sjurte in Carapthian Ruthenia in 1922. He and his brother Herman were abducted to a

Hungarian labour camp in 1943. This saved their lives – the rest of the family died in Nazi concentration camps. Following liberation Lieberman moved to Uzzhorod

and in April 1946 married Elizaveta Šumbergerová, one of the few to return from Auschwitz. He managed to take up the option of Czechoslovak citizenship in 1945 but

that choice was not open to his wife. They therefore decided to illegally leave the then Soviet Carpathian Ukraine for relatives in Satu Mare, Romania, from where

they hoped to continue on to Czechoslovakia. The Liebermans’ friend from Sjurte, cobbler Arpád Elkovič (born 1908), and his wife Olg Elkovič (1927),

who had survived the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, decided to join them in their escape. On the night of 27 October 1946 the two couples were arrested by Soviet

border guards, about 80 metres from the Romanian border near the village of Černa, and handed over to the NKVD. They released Elizaveta after several months as she

was pregnant. Evžen Lieberman was charged with organising a group border crossing. A year later, on Christmas Eve 1947, he was sentenced to three years in jail by

a military tribunal in Uzzhorod. He served that time in Gulag camps around the northern city of Ukhta in the Komi Republic. His friend Arpád Elkovič also got forced

labour but never returned from the Soviet camps. Evžen Lieberman was eventually released and was first sent to Poland, where with the help of the American Jewish Joint

Distribution Committee (JOINT) he illegally crossed into Czechoslovakia. There he legalised his stay and was reunited with his wife and the son he had never known.

In Czechoslovakia Lieberman became involved in Jewish Community and JOINT underground activities. This mainly comprised the smuggling of Jewish refugees from central

European Communist states to Austria, from where they continued to Palestine. His brother Herman was also active in this endeavour. When they were discovered Herman was

tortured to death in investigative custody at Prague’s Ruznyě prison. Evžen Lieberman got a seven-year jail term. Following his release in 1965 he was permitted to travel

to Israel with his son. Before his departure he wrote his memoirs, the handwritten manuscript MUKL – muž určený k likvidaci (Man Intended for Liquidation)..

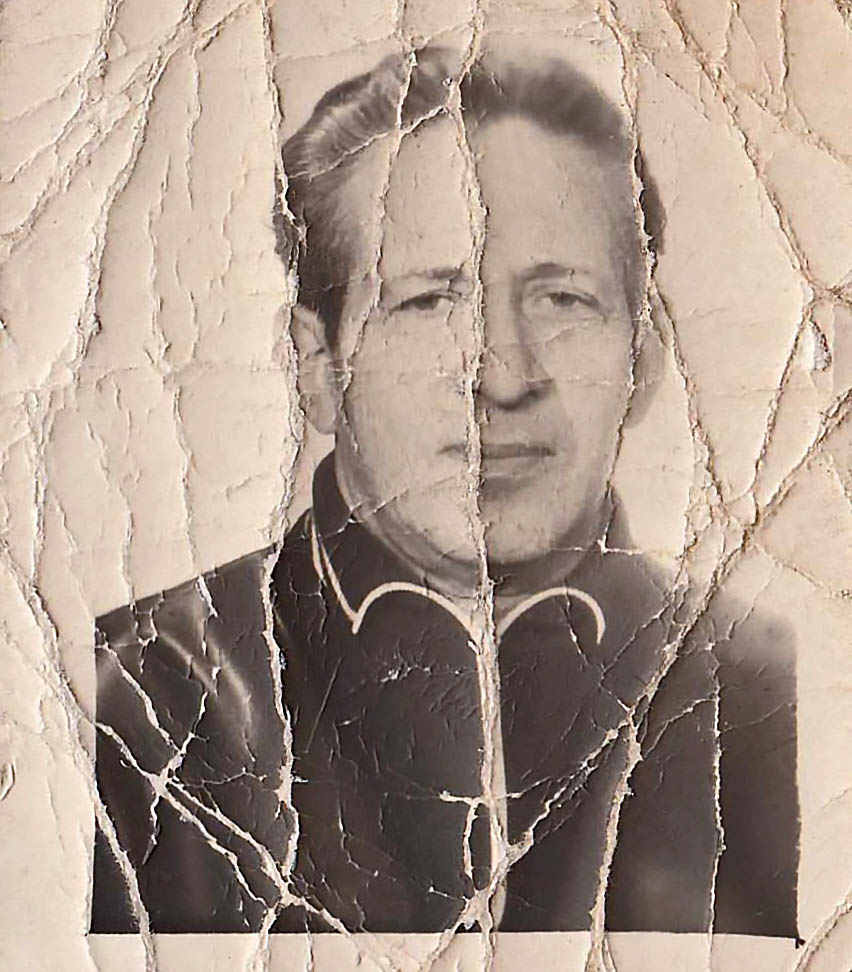

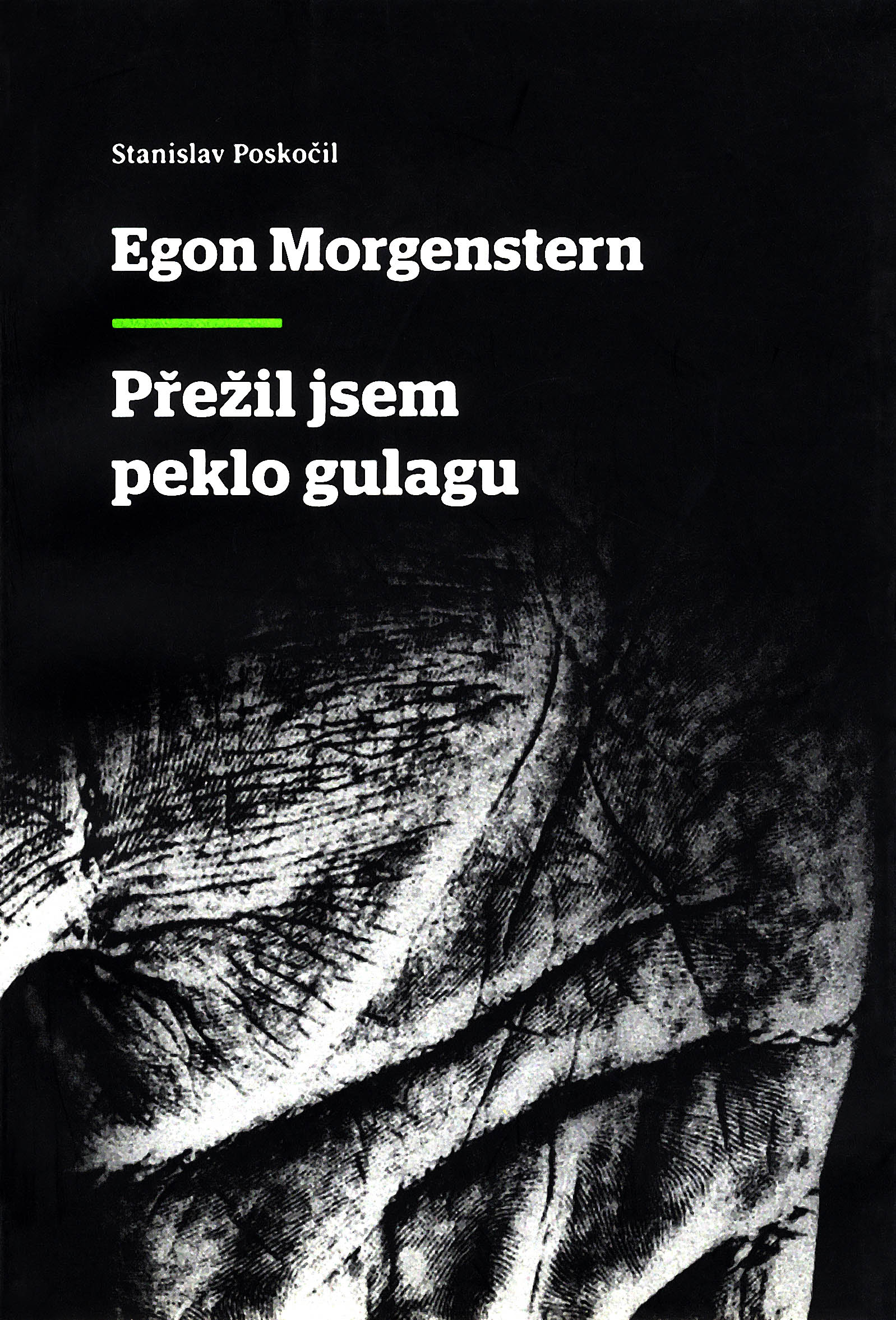

Egon Morgenstern (1914–2016)

Přežil jsem peklo Gulagu (I Survived the Hell of the Gulag). Nakladatelství P3K, 2015

Imprisoned in 1939–1945: Vilnius (Lukishke), Pechorlag, Karlag

Egon Morgenstern was born into a Jewish family in Fryštát on 27 July 1914. A tough social situation meant he could not complete elementary school and at the age of 14 he became a waiter. In 1936 he began basic military service. In June 1939 he, his sister Fanka and younger brother Armin escaped to Poland and he reported as a volunteer soldier at the Czechoslovak consulate in Krakow. However, a few days later he was arrested by Polish police and taken to Krakow prison, where he spent several weeks. Even without his papers, which the police had confiscated, he was determined to reach Riga and from there to cross the sea to Sweden. He was arrested in the Soviet city of Dvinsk (today Daugavpils). After four months of interrogations and charges of illegally entering territory of the USSR he was convicted at Vilnius’s Lukishke prison by a so-called troika (a non-judicial body), receiving five years in the labour camps for illegally crossing the border and espionage. After a miserable train journey lasting weeks Morgenstern found himself in March 1940 in Kotlas, from where the prisoners continued their journey on foot. Roughly a month later they arrived at a forlorn spot where they first had to build one of the camps of the Pechorlag. They later worked in cruel conditions on the construction of a railroad from Kotlas to Vorkuta. Morgenstern had been sentenced for espionage and had no papers, so an amnesty of Czechoslovak citizens did not apply to him. In April 1943 he was sent from Pechorlag to another labour camp near Aktyubinsk in Kazhakhstan. It was there that he was finally released, in July 1945. However, he was barred from leaving the region and had to regularly report to the police. In exile he worked as a driver at an agricultural collective before later getting into geological research. He succeeded in escaping from there and following adventure-filled wanderings he reached Moscow. However, without the permission of the Soviet authorities he could not leave the USSR, so he remained there. He visited Czechoslovakia for the first time in 1960 but did not receive permanent residence. In the same year he moved to Vilnius and worked as an apartment painter until his retirement. He did not receive permanent residence in Czechoslovakia until after 1989 and was prevented from moving by the health condition of his wife. Egon Morgenstern died in Vilnius in 2016.

Egon Morgenstern was born into a Jewish family in Fryštát on 27 July 1914. A tough social situation meant he could not complete elementary school and at the age of 14 he became a waiter. In 1936 he began basic military service. In June 1939 he, his sister Fanka and younger brother Armin escaped to Poland and he reported as a volunteer soldier at the Czechoslovak consulate in Krakow. However, a few days later he was arrested by Polish police and taken to Krakow prison, where he spent several weeks. Even without his papers, which the police had confiscated, he was determined to reach Riga and from there to cross the sea to Sweden. He was arrested in the Soviet city of Dvinsk (today Daugavpils). After four months of interrogations and charges of illegally entering territory of the USSR he was convicted at Vilnius’s Lukishke prison by a so-called troika (a non-judicial body), receiving five years in the labour camps for illegally crossing the border and espionage. After a miserable train journey lasting weeks Morgenstern found himself in March 1940 in Kotlas, from where the prisoners continued their journey on foot. Roughly a month later they arrived at a forlorn spot where they first had to build one of the camps of the Pechorlag. They later worked in cruel conditions on the construction of a railroad from Kotlas to Vorkuta. Morgenstern had been sentenced for espionage and had no papers, so an amnesty of Czechoslovak citizens did not apply to him. In April 1943 he was sent from Pechorlag to another labour camp near Aktyubinsk in Kazhakhstan. It was there that he was finally released, in July 1945. However, he was barred from leaving the region and had to regularly report to the police. In exile he worked as a driver at an agricultural collective before later getting into geological research. He succeeded in escaping from there and following adventure-filled wanderings he reached Moscow. However, without the permission of the Soviet authorities he could not leave the USSR, so he remained there. He visited Czechoslovakia for the first time in 1960 but did not receive permanent residence. In the same year he moved to Vilnius and worked as an apartment painter until his retirement. He did not receive permanent residence in Czechoslovakia until after 1989 and was prevented from moving by the health condition of his wife. Egon Morgenstern died in Vilnius in 2016.

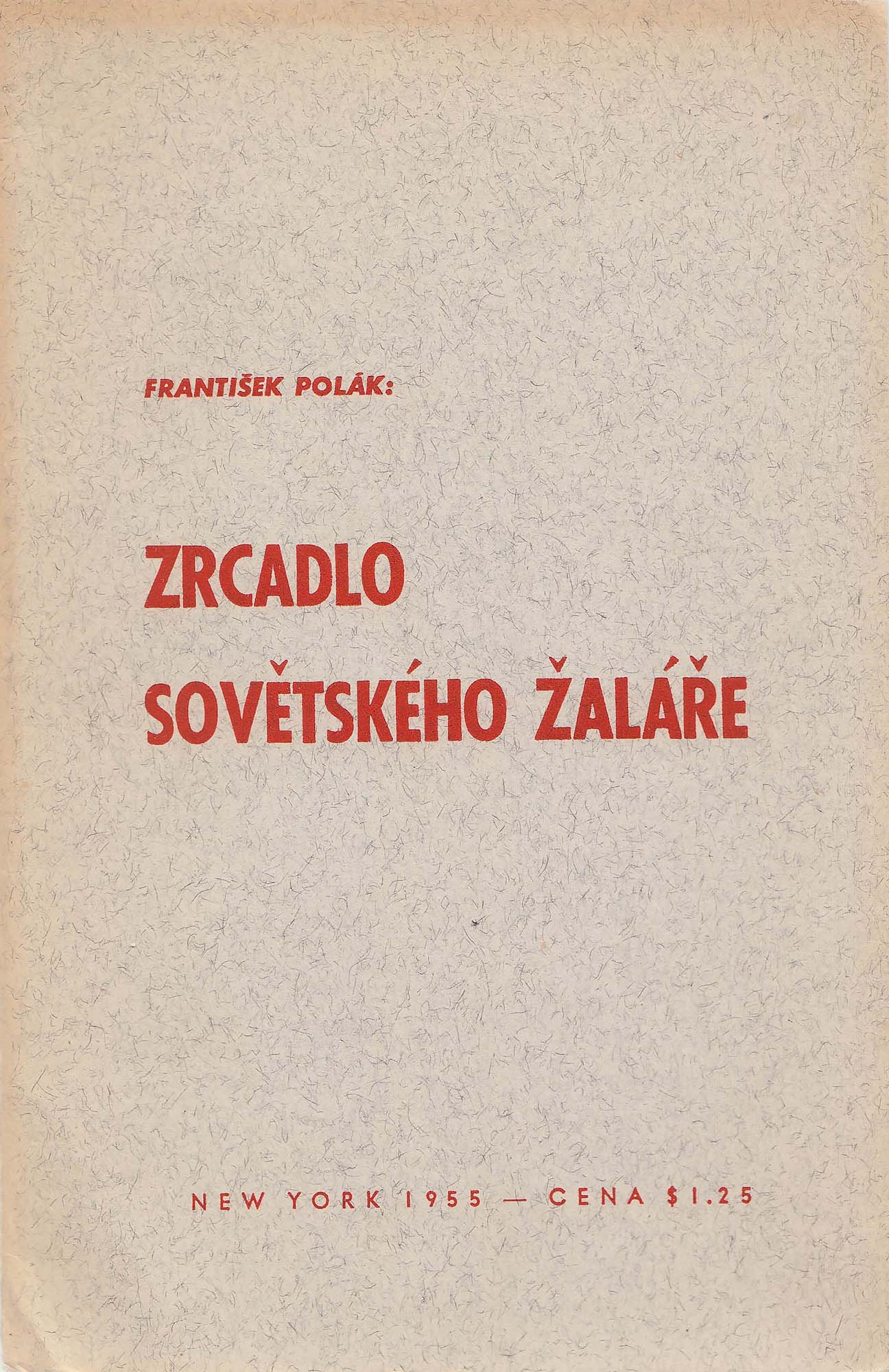

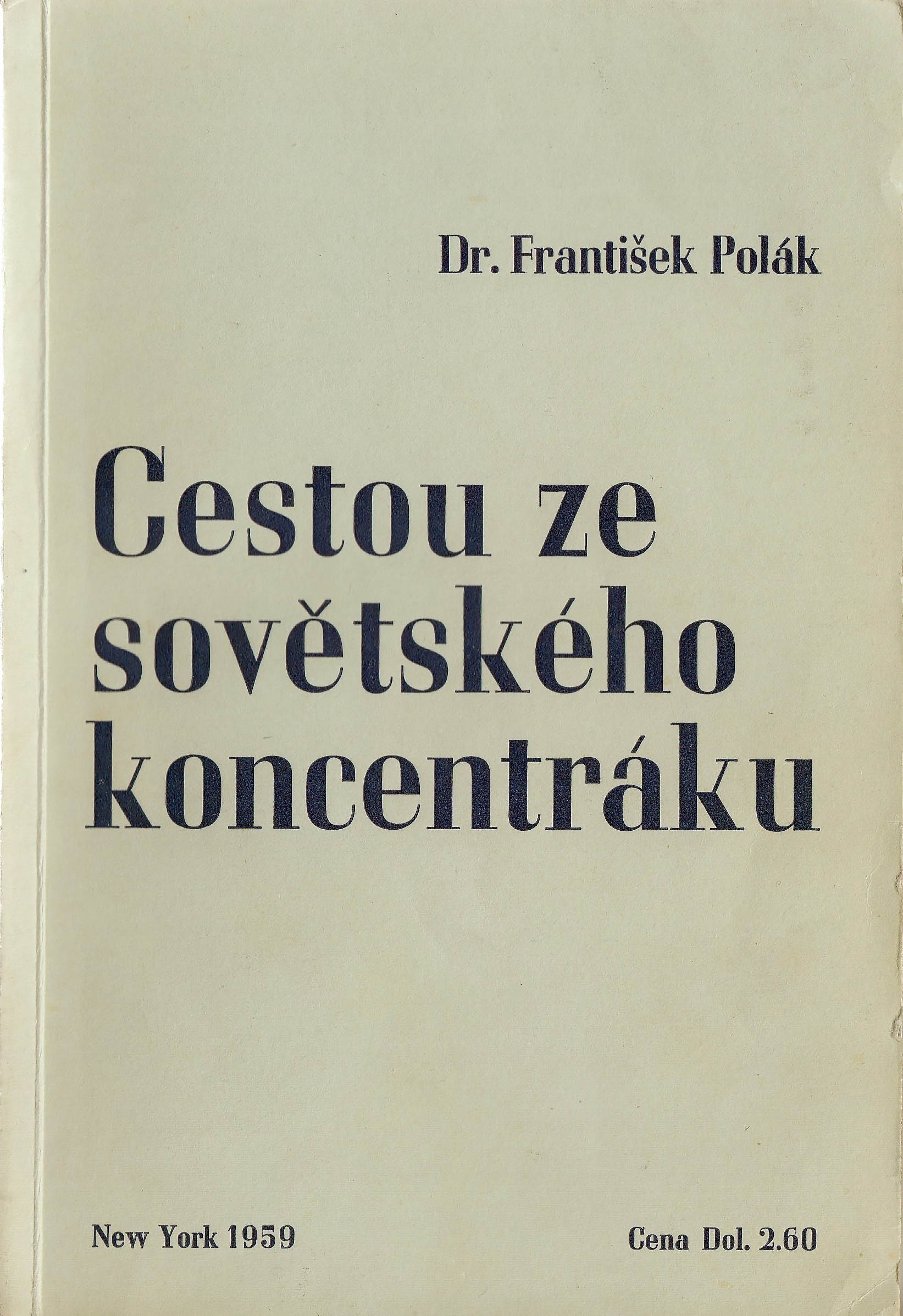

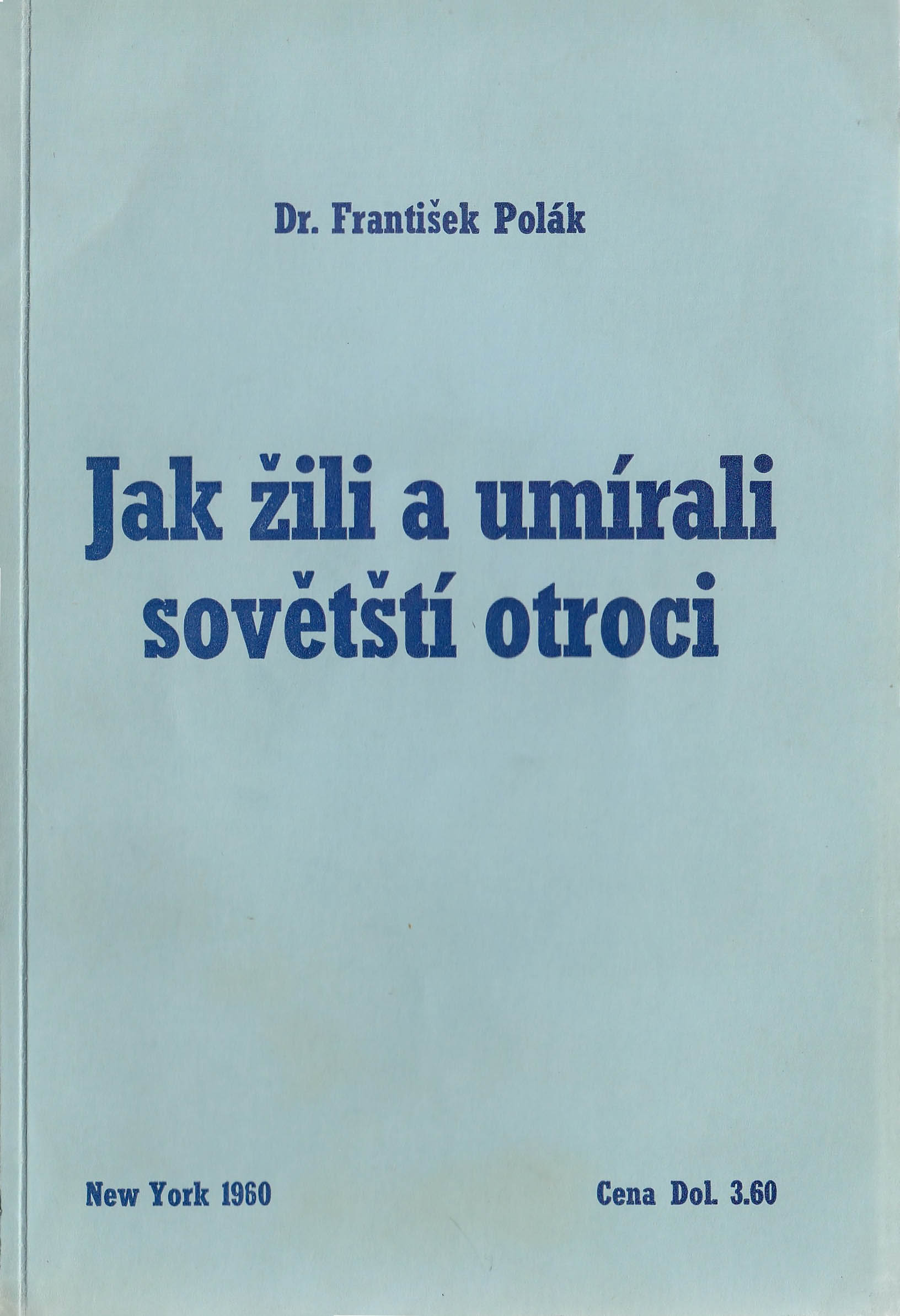

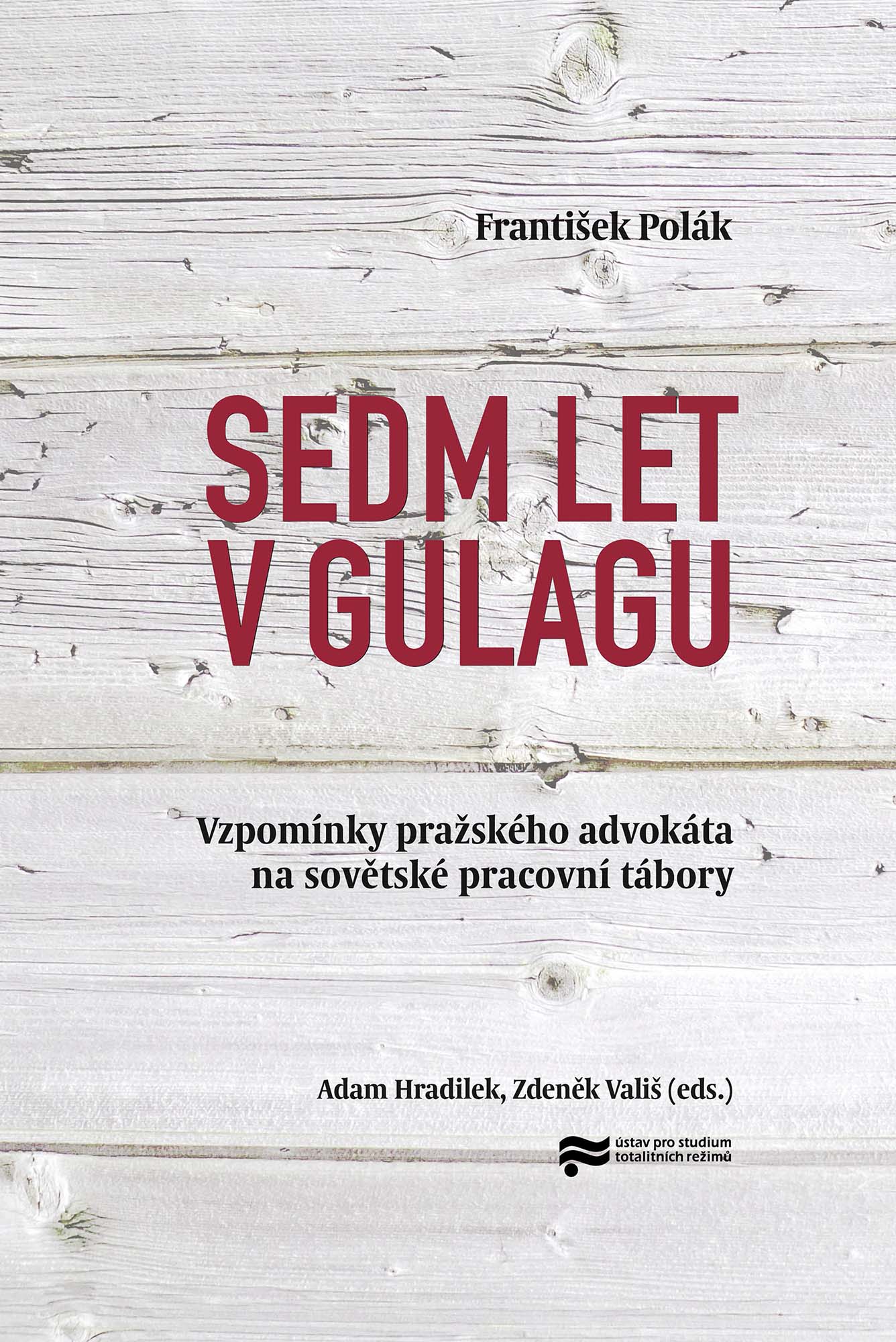

František Polák (1889–1971)

Zrcadlo sovětského žaláře (The Mirror of a Soviet Jailer). Self-published, New York 1955

Cestou ze sovětského koncentráku (Journey from a Soviet Concentration Camp). Self-published, New York 1959

Jak žili a umírali sovětští otroci (How Soviet Slaves Lived and Died). Self-published, New York 1960

Sedm let v Gulagu – sebrané memoáry F. Poláka (Seven Years in the Gulag – Selected Memoirs of F. Polák). Ústav pro studium totalitních režimů, 2015

Imprisoned in 1939–1947: Moscow (Lefortovo, Butyrka), Norillag, Unzhlag

František Polák was born on 27 December 1889 in Hostomice near Příbram. He studied law at Charles University. During WWI he was captured by the Russians. He entered the Czechoslovak foreign army in Russia and went back to his homeland on the first transport of legionnaires. After his return in June 1920 he completed a law doctorate and defended workers and Communist activists. He wrote a number of specialist pieces on that subject and also published a propaganda brochure on the good conditions in Soviet jails. In August 1939 he fled Nazi persecution for Poland and in Krakow entered a nascent Czechoslovak military unit that was captured by the Soviets. After being denounced by Czechoslovak Communists, who accused him of Trotskyism, he and eight other soldiers were arrested on 3 November 1939 and imprisoned at Moscow’s Lubyanka prison. At another prison in the city, Butryka, he was convicted on 16 June 1940 of counterrevolutionary activities and sentenced to eight years’ hard labour in the Gulag camps. He was later transported to Norillag, where in the following year and a half he worked in mines, on road construction and clearing snow. On 17 January 1942 he was released under an amnesty and sent to the Czechoslovak unit in Buzuluk. In view of the fact that he refused to take part in pro-Soviet instruction of the Czechoslovak troops he again fell foul of Czechoslovak Communists and Soviet security agencies. At the end of 1942, with the involvement of Ludvík Svoboda, he and three other Czechoslovaks were arrested by the NKVD and sentenced in Moscow to five years in the Unzhlag labour camps for anti-Soviet activities. He got out on 5 December 1947. Physically and mentally exhausted, he returned on 7 March 1948 to Czechoslovakia, where a Communist putsch had just taken place. He therefore emigrated again at the start of September 1948. He first spent time in Germany, where in 1949 he began, with the help of Pavel Tigrid, to inform the Western public about the Soviet camps. A year later he was a witness in a Paris trial in which David Rousset took the Communist magazine Les Lettres françaises to court. In April 1951 he moved to the US, where he tirelessly alerted the world to the repressive nature of the Soviet system and the existence of the Gulag camps. As well as in interviews for the media and public discussions, he also spoke at the UN. Until his retirement he worked as a cleaner and night watchman, which did not prevent him from bringing out publications at his own expense in the late 1950s. František Polák died on 15 April 1970 in the town of Coxsackie in New York State. The Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes issued an anthology of his writings in 2015.

František Polák was born on 27 December 1889 in Hostomice near Příbram. He studied law at Charles University. During WWI he was captured by the Russians. He entered the Czechoslovak foreign army in Russia and went back to his homeland on the first transport of legionnaires. After his return in June 1920 he completed a law doctorate and defended workers and Communist activists. He wrote a number of specialist pieces on that subject and also published a propaganda brochure on the good conditions in Soviet jails. In August 1939 he fled Nazi persecution for Poland and in Krakow entered a nascent Czechoslovak military unit that was captured by the Soviets. After being denounced by Czechoslovak Communists, who accused him of Trotskyism, he and eight other soldiers were arrested on 3 November 1939 and imprisoned at Moscow’s Lubyanka prison. At another prison in the city, Butryka, he was convicted on 16 June 1940 of counterrevolutionary activities and sentenced to eight years’ hard labour in the Gulag camps. He was later transported to Norillag, where in the following year and a half he worked in mines, on road construction and clearing snow. On 17 January 1942 he was released under an amnesty and sent to the Czechoslovak unit in Buzuluk. In view of the fact that he refused to take part in pro-Soviet instruction of the Czechoslovak troops he again fell foul of Czechoslovak Communists and Soviet security agencies. At the end of 1942, with the involvement of Ludvík Svoboda, he and three other Czechoslovaks were arrested by the NKVD and sentenced in Moscow to five years in the Unzhlag labour camps for anti-Soviet activities. He got out on 5 December 1947. Physically and mentally exhausted, he returned on 7 March 1948 to Czechoslovakia, where a Communist putsch had just taken place. He therefore emigrated again at the start of September 1948. He first spent time in Germany, where in 1949 he began, with the help of Pavel Tigrid, to inform the Western public about the Soviet camps. A year later he was a witness in a Paris trial in which David Rousset took the Communist magazine Les Lettres françaises to court. In April 1951 he moved to the US, where he tirelessly alerted the world to the repressive nature of the Soviet system and the existence of the Gulag camps. As well as in interviews for the media and public discussions, he also spoke at the UN. Until his retirement he worked as a cleaner and night watchman, which did not prevent him from bringing out publications at his own expense in the late 1950s. František Polák died on 15 April 1970 in the town of Coxsackie in New York State. The Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes issued an anthology of his writings in 2015.

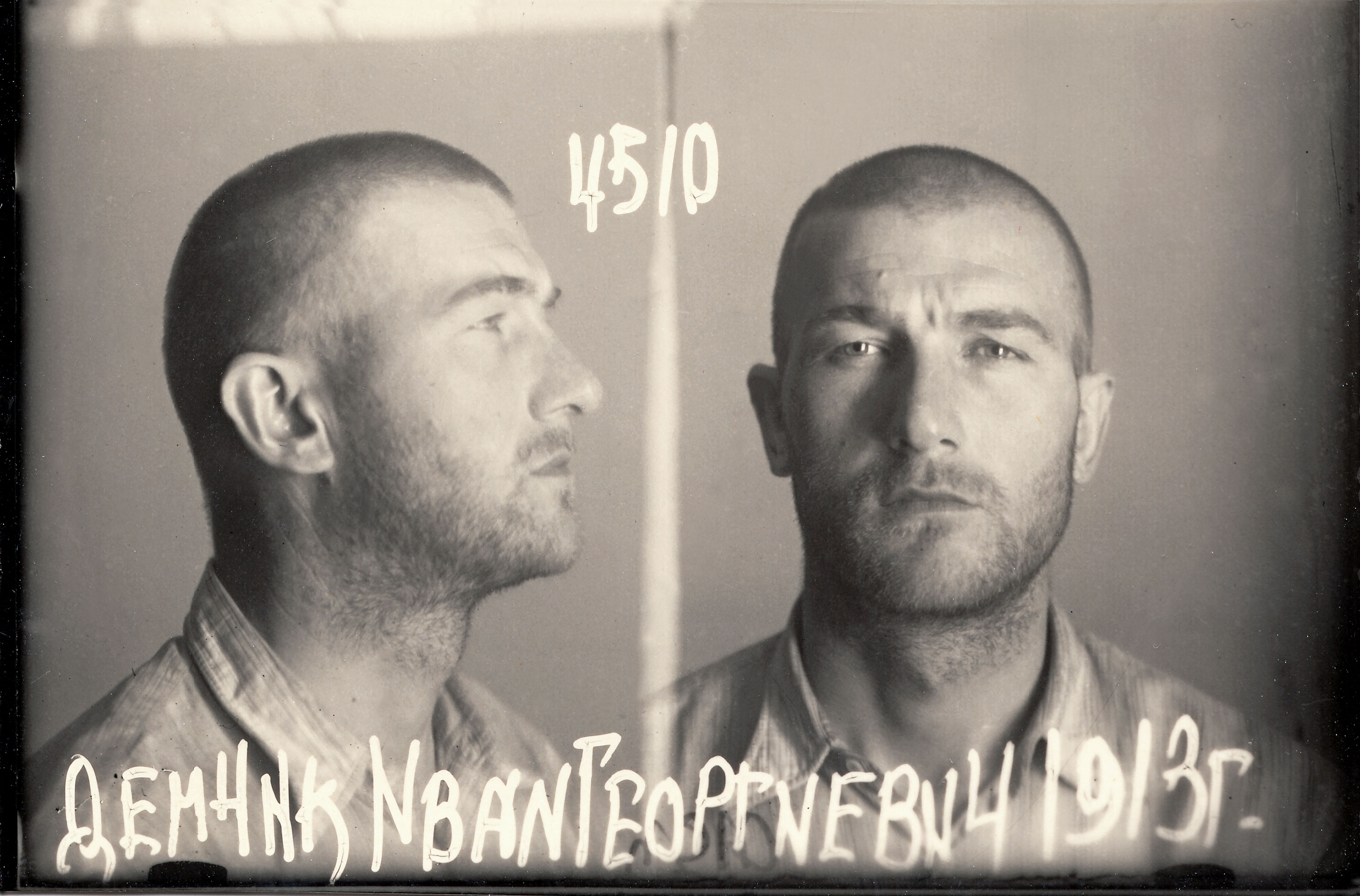

Jan Demčík (1913–2005)

Můj útěk do gulagu. (My Escape to the Gulag). Memoirs edited by Karel Richter. Česká expedice, 1995

Imprisoned in 1940–1942: Stanislavov, Poltava, Charkov, Vorkutlag, Orenburg

Jan Demčík was born in the Carpathian Ruthenian village of Voloská on 15 February 1913. After completing general school he graduated from a business school in Mukačev. On 13 August 1940 he and friends Roman (born 1920) and Baganič (1914) escaped Hungary’s oppressive policies to the Soviet Union. Hoping to receive asylum, they instead encountered prison and interrogations after crossing the border. On 7 April 1941 Jan Demčík was sentenced in Kharkov to three years’ forced labour for illegally crossing the border. From Kharkov he was sent to one of the Vorkutlag camps, where he helped construct a Kotlas–Vorkuta railway line. Exhaustion and a lack of vitamins soon left him seriously ill and he spent a number of weeks at the camp hospital, where for lack of medicines they treated people with pea sprouts. Following an amnesty of Czechoslovak Gulag prisoners in 1942 Demčík was transferred to Jambyl to convalesce and then sent to the Czechoslovak unit in Buzuluk. However he was arrested on route by the NKVD and was only released to join the Czechoslovak force after interrogations that further complicated his journey. Demčík’s friend Baganič, with whom he had fled Czechoslovakia, died in Vorkuta on 12 June 1942. The third member of their group, Roman, was released four days later and sent to the Czechoslovak military unit in Buzuluk. Demčík himself signed up there on 12 June 1943. As the commander of a tank battalion he took part in the Dukla operation and the battle for Ostrava. After the war he remained in the Czechoslovak Army until August 1968, when he quit in protest at the Soviet occupation. Jan Demčík recorded his experiences of the Soviet Union but they could only be published following the fall of the Communist regime. He died in 2005.

Jan Demčík was born in the Carpathian Ruthenian village of Voloská on 15 February 1913. After completing general school he graduated from a business school in Mukačev. On 13 August 1940 he and friends Roman (born 1920) and Baganič (1914) escaped Hungary’s oppressive policies to the Soviet Union. Hoping to receive asylum, they instead encountered prison and interrogations after crossing the border. On 7 April 1941 Jan Demčík was sentenced in Kharkov to three years’ forced labour for illegally crossing the border. From Kharkov he was sent to one of the Vorkutlag camps, where he helped construct a Kotlas–Vorkuta railway line. Exhaustion and a lack of vitamins soon left him seriously ill and he spent a number of weeks at the camp hospital, where for lack of medicines they treated people with pea sprouts. Following an amnesty of Czechoslovak Gulag prisoners in 1942 Demčík was transferred to Jambyl to convalesce and then sent to the Czechoslovak unit in Buzuluk. However he was arrested on route by the NKVD and was only released to join the Czechoslovak force after interrogations that further complicated his journey. Demčík’s friend Baganič, with whom he had fled Czechoslovakia, died in Vorkuta on 12 June 1942. The third member of their group, Roman, was released four days later and sent to the Czechoslovak military unit in Buzuluk. Demčík himself signed up there on 12 June 1943. As the commander of a tank battalion he took part in the Dukla operation and the battle for Ostrava. After the war he remained in the Czechoslovak Army until August 1968, when he quit in protest at the Soviet occupation. Jan Demčík recorded his experiences of the Soviet Union but they could only be published following the fall of the Communist regime. He died in 2005.

Karel Goliath (1901–1985)

Zápisky ze stalinských koncentráků (Notes from Stalin’s Concentration Camps). Index émigré publishing house, Cologne 1986

Imprisoned in 1939–1955: Moscow (Lubyanka, Butyrka), Uchtizhemlag, Sevzheldorlag, Karlag, Tagillag

Karel Goliath was born into a politically engaged family in Jičín on 10 September 1901. At 15 he joined the Czechoslovak Social Democratic Workers Party and was actively involved in the establishment of the Communist Party in 1921, becoming a founding member. He studied history and philosophy in Berlin and law in Prague and eventually became a lawyer. In 1927 he quit the Communist Party in response to its Bolshevikisation. On the day German troops entered Czechoslovakia in March 1939 a search of his Ostrava apartment was carried out. Goliath had managed to go into hiding and in late June 1939 fled to Krakow. At the start of August 1939 he joined a nascent Czechoslovak foreign unit in Bronowice. His parents and brother, who had remained in the occupied homeland, perished in Nazi concentration camps. The military unit comprising refugees, the so-called Czech and Slovak legion, was interned by the Soviets at Kamieniec Podolski when Poland was divided by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. Following denunciations and inspections, Goliath and 20 other soldiers were arrested by the NKVD on 3 November 1939. He was taken to Moscow’s Lubyanka prison, where at the end of July 1940 he was sentenced (the length of the term is unknown) to labour in the Gulag for anti-Soviet opinions. Following several days at Moscow’s Butyrka prison he was sent on 5 August 1940 to Uchtizhemlag in the north of Russia. When he became seriously ill there he was transferred to the nearby Kyltovo camp (part of Sevzheldorlag). In January 1942, on the basis of an amnesty, he was released into the newly formed Czechoslovak military unit in Buzuluk, reporting on 12 February 1942. In December of that year he was again arrested. He was taken to Moscow and was sentenced to another five years’ forced labour for “anti-Soviet activity and Trotskyism”. He was sentenced for a third time in 1949, this time to 10 years, serving the term at the Karlag and Tagillag camps. In total he spent close to 17 years at Soviet labour camps. He finally got out in 1955. Following his return to Czechoslovakia in November 1955 he openly criticised the political situation and demanded compensation for the years spent in Soviet camps. His untiring efforts to attain justice brought him into conflict with the totalitarian regime. He was therefore persecuted again and was unlawfully placed in a psychiatric clinic for several months. Karel Goliath died in Ostrava in 1985. His complete memoirs, which are not in order, are to be found in his estate in the archive of the National Museum in Prague.

Karel Goliath was born into a politically engaged family in Jičín on 10 September 1901. At 15 he joined the Czechoslovak Social Democratic Workers Party and was actively involved in the establishment of the Communist Party in 1921, becoming a founding member. He studied history and philosophy in Berlin and law in Prague and eventually became a lawyer. In 1927 he quit the Communist Party in response to its Bolshevikisation. On the day German troops entered Czechoslovakia in March 1939 a search of his Ostrava apartment was carried out. Goliath had managed to go into hiding and in late June 1939 fled to Krakow. At the start of August 1939 he joined a nascent Czechoslovak foreign unit in Bronowice. His parents and brother, who had remained in the occupied homeland, perished in Nazi concentration camps. The military unit comprising refugees, the so-called Czech and Slovak legion, was interned by the Soviets at Kamieniec Podolski when Poland was divided by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. Following denunciations and inspections, Goliath and 20 other soldiers were arrested by the NKVD on 3 November 1939. He was taken to Moscow’s Lubyanka prison, where at the end of July 1940 he was sentenced (the length of the term is unknown) to labour in the Gulag for anti-Soviet opinions. Following several days at Moscow’s Butyrka prison he was sent on 5 August 1940 to Uchtizhemlag in the north of Russia. When he became seriously ill there he was transferred to the nearby Kyltovo camp (part of Sevzheldorlag). In January 1942, on the basis of an amnesty, he was released into the newly formed Czechoslovak military unit in Buzuluk, reporting on 12 February 1942. In December of that year he was again arrested. He was taken to Moscow and was sentenced to another five years’ forced labour for “anti-Soviet activity and Trotskyism”. He was sentenced for a third time in 1949, this time to 10 years, serving the term at the Karlag and Tagillag camps. In total he spent close to 17 years at Soviet labour camps. He finally got out in 1955. Following his return to Czechoslovakia in November 1955 he openly criticised the political situation and demanded compensation for the years spent in Soviet camps. His untiring efforts to attain justice brought him into conflict with the totalitarian regime. He was therefore persecuted again and was unlawfully placed in a psychiatric clinic for several months. Karel Goliath died in Ostrava in 1985. His complete memoirs, which are not in order, are to be found in his estate in the archive of the National Museum in Prague.

Josef Klička (1889–1957)

Žil jsem v SSSR (I Lived in the USSR). Orbis, 1942

Neznámé sověty (The Unknown Soviets). Orbis, 1944

Imprisoned in 1937–1940: Novosibirsk, Moscow (Butyrka), Verchneuralsk, Solovetsky special camp

Josef Klička was born into a farming family in the village of Hraběšín near Čáslav on 16 March 1889. After general school and lower grammar school in Hradec Králové he attended upper vocational school in Ostrava. He later worked on the family farm. During WWI he was captured by the Russians and as a POW worked building a railway from Yekaterinburg to Tobolsk. In spring 1918 he married teacher and Antonie Nikolajeva and in the autumn he joined the Czechoslovak Legions in Omsk. However, instead of returning to the homeland he decided to live in the Soviet Union and left the legions in January 1920. He crisscrossed the USSR taking on all kinds of jobs. In the mid-1930s he found work at the Kuznetsk mining basin near Prokopyevsk, where he was head of a coalfield. He was arrested on the basis of a denouncement during the Great Terror, on 23 February 1937. After a year and a half in custody he was tried in Novosibirsk on 26 October 1938, receiving 20 years on charges of espionage, destruction of state property and agitation against the Slovak government. His wife and children were expelled from the USSR and left for Czechoslovakia. Klička passed through a number of Gulag camps, including on the Solovetsky Islands. In 1940 he was transferred to Moscow for a reopening of his trial by the Supreme Military Court of the Soviet Union. This was most unusual in the Stalinist period, as was his subsequent receipt of a pardon and expulsion from the USSR. By coincidence Klička had appeared on a list of political prisoners to be exchanged by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. He rejoined his family in the Protectorate in February 1941. They initially lived from hand to mouth but that changed following the German invasion of the USSR when, at the urging of the occupiers, Klička published a series of anti-Soviet articles in the Protectorate press. In 1942 publishers Orbis brought out his Žil jsem v SSSR (I Lived in the USSR), in which he described the Bolshevik regime as a reign of terror that was destroying Soviet society politically, economically, culturally and spiritually and debasing interpersonal relationships and living standards. Klička’s best-known anti-Soviet screed was based chiefly on personal experience and in many ways faithfully described the Soviet reality. However, the fact he made abundant use of German-supplied propaganda materials remains problematic.

Josef Klička was born into a farming family in the village of Hraběšín near Čáslav on 16 March 1889. After general school and lower grammar school in Hradec Králové he attended upper vocational school in Ostrava. He later worked on the family farm. During WWI he was captured by the Russians and as a POW worked building a railway from Yekaterinburg to Tobolsk. In spring 1918 he married teacher and Antonie Nikolajeva and in the autumn he joined the Czechoslovak Legions in Omsk. However, instead of returning to the homeland he decided to live in the Soviet Union and left the legions in January 1920. He crisscrossed the USSR taking on all kinds of jobs. In the mid-1930s he found work at the Kuznetsk mining basin near Prokopyevsk, where he was head of a coalfield. He was arrested on the basis of a denouncement during the Great Terror, on 23 February 1937. After a year and a half in custody he was tried in Novosibirsk on 26 October 1938, receiving 20 years on charges of espionage, destruction of state property and agitation against the Slovak government. His wife and children were expelled from the USSR and left for Czechoslovakia. Klička passed through a number of Gulag camps, including on the Solovetsky Islands. In 1940 he was transferred to Moscow for a reopening of his trial by the Supreme Military Court of the Soviet Union. This was most unusual in the Stalinist period, as was his subsequent receipt of a pardon and expulsion from the USSR. By coincidence Klička had appeared on a list of political prisoners to be exchanged by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. He rejoined his family in the Protectorate in February 1941. They initially lived from hand to mouth but that changed following the German invasion of the USSR when, at the urging of the occupiers, Klička published a series of anti-Soviet articles in the Protectorate press. In 1942 publishers Orbis brought out his Žil jsem v SSSR (I Lived in the USSR), in which he described the Bolshevik regime as a reign of terror that was destroying Soviet society politically, economically, culturally and spiritually and debasing interpersonal relationships and living standards. Klička’s best-known anti-Soviet screed was based chiefly on personal experience and in many ways faithfully described the Soviet reality. However, the fact he made abundant use of German-supplied propaganda materials remains problematic.

In 1944 Orbis published another book by Klička on the same theme, Neznámé sověty (The Unknown Soviets). From June 1942 Klička worked at the press department of the National Trade Unions Headquarters. He became editor-in-chief in June 1943 and later chief secretary for press and propaganda. In January 1944 he also joined the Czech League Against Bolshevism. When the war ended he was arrested in May 1945. On 23 January 1947 he was sentenced by an Extraordinary People’s Court in Prague to 15 years in prison for crimes against the state according to article 3/1 of a presidential decree. He was released in late February 1954 under an amnesty declared by the president. On his release he was a warehouse worker and later a doorman at the Obchodní domy national enterprise. Josef Klička died in September 1957.

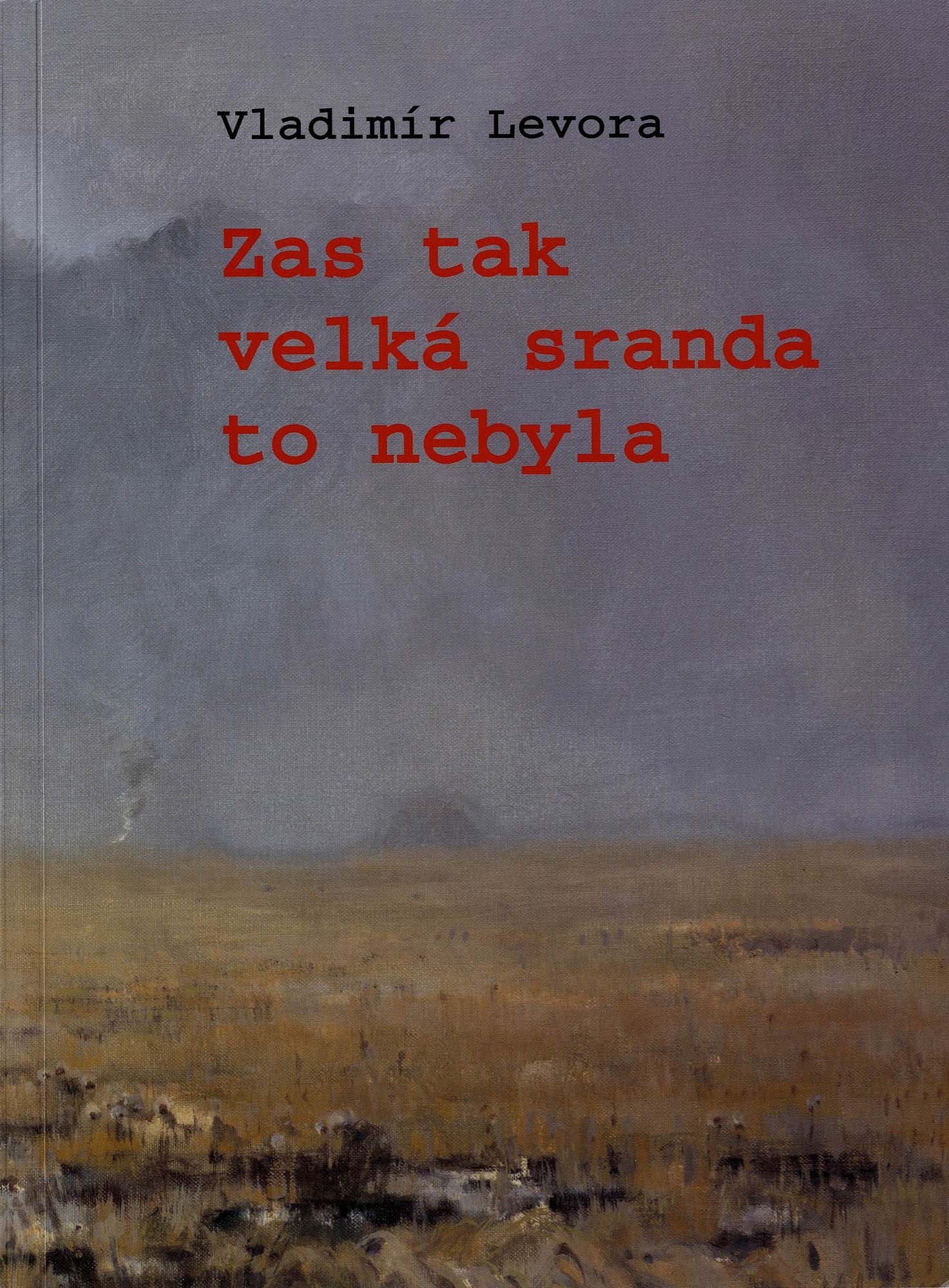

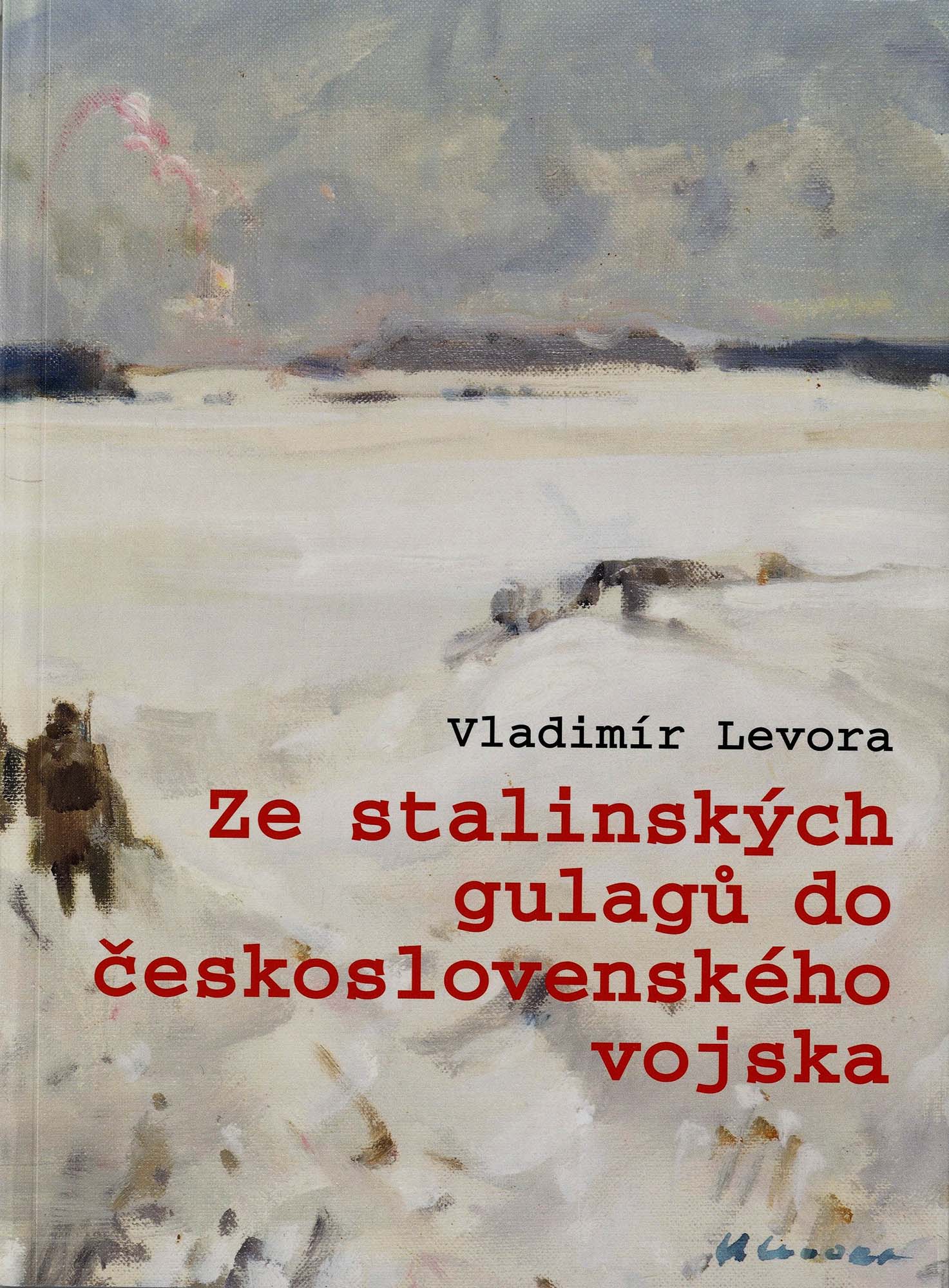

Vladimír Levora (1920–1999)

Ze stalinských gulagů do Československého vojska (From Stalin’s Gulags to the Czechoslovak Army). Nakladatelství Hříbal, 1993

Zas tak velká sranda to nebyla (It wasn't that much fun). Galerie Klatovy / Klenová, 2020

Ze stalinských gulagů do Československého vojska (From Stalin’s Gulags to the Czechoslovak Army). GALERIE KLATOVY Galerie Klatovy / Klenová, Ústav pro studium totalitních režimů, 2020

Imprisoned in 1939–1942: Vorota, Nadvirna, Stanislavov, Poltava, Vorkutlag (camp no. 2)

Vladimír Levora was born in the village of Křižovice in West Bohemia on 14 July 1920. After elementary school he attended grammar school and was set to enter a teaching faculty in autumn 1939. At that time he was an active member of a student resistance group in Pilsen that destroyed supplies in German army stores. After they were betrayed, Levora and another member of the group, Vladimír Ptáčník, fled the Gestapo to Poland, where they obtained visas to enter the UK at the British consulate in Katowice. They were due to sail from Gdynia on 6 September. However, when Hitler’s Germany invaded Poland on 1 September the two refugees’ situation was instantly transformed. They fled the advancing Germans to the east of the country and inadvertently found themselves in the Soviet Union, which on 17 September 1939 had begun occupying eastern Poland. Levora, Ptáčník and another refugee, Jaroslav Berger, attempted to reach Romania, where they planned to join Czechoslovak military units. Instead Soviet soldiers arrested them on the border and they were sent to Vorota. Via prison in Nadvirna they were, now without Ptáčník, transported to Stanislavov and finally to Poltava. Though Levora had not crossed the border illegally and found himself in the USSR against his will he was convicted in Poltava of illegally crossing the border and got three years’ forced labour. In autumn 1940 he was sent to camp no. 2 in the Vorkutlag in north-eastern Russia, where prisoners worked in forestry, mining and railway construction. Levora was saved from heavy work in the freezing tundra by his creative skills and became the camp painter. In November 1942 he was released from the camp and called up to the newly formed Czechoslovak military unit in Buzuluk. As a member of a machine gun company he fought at Sokolovo, where he was seriously injured. Once he had recovered he took part in further fighting during the liberation of Czechoslovakia, for which he was decorated. In 1946 Levora left the army and became a civilian employee at the Asta Plzeň architecture studio. A year later he entered the Communist Party, though he soon stood down. At this time he began penning a memoir of his time in the Soviet Union. He stopped writing after February 1948 and did not complete the manuscript until 1956. Following a denunciation the StB searched his home, confiscating the manuscript. Levora was accused of spreading defamation and on 24 September 1954 received an 18-month conviction for “sedition” and “defaming an allied state”. He served his term at the Bory and Valdice prisons. He was later a freelance painter (in 1951 he graduated as an art teacher from the Faculty of Pedagogy in Pilsen). In the 1960s he set up and ran an art gallery in Klatovy. He finally published his memoir of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s. Vladimír Levora died in Klatovy on 27 May 1999.

Vladimír Levora was born in the village of Křižovice in West Bohemia on 14 July 1920. After elementary school he attended grammar school and was set to enter a teaching faculty in autumn 1939. At that time he was an active member of a student resistance group in Pilsen that destroyed supplies in German army stores. After they were betrayed, Levora and another member of the group, Vladimír Ptáčník, fled the Gestapo to Poland, where they obtained visas to enter the UK at the British consulate in Katowice. They were due to sail from Gdynia on 6 September. However, when Hitler’s Germany invaded Poland on 1 September the two refugees’ situation was instantly transformed. They fled the advancing Germans to the east of the country and inadvertently found themselves in the Soviet Union, which on 17 September 1939 had begun occupying eastern Poland. Levora, Ptáčník and another refugee, Jaroslav Berger, attempted to reach Romania, where they planned to join Czechoslovak military units. Instead Soviet soldiers arrested them on the border and they were sent to Vorota. Via prison in Nadvirna they were, now without Ptáčník, transported to Stanislavov and finally to Poltava. Though Levora had not crossed the border illegally and found himself in the USSR against his will he was convicted in Poltava of illegally crossing the border and got three years’ forced labour. In autumn 1940 he was sent to camp no. 2 in the Vorkutlag in north-eastern Russia, where prisoners worked in forestry, mining and railway construction. Levora was saved from heavy work in the freezing tundra by his creative skills and became the camp painter. In November 1942 he was released from the camp and called up to the newly formed Czechoslovak military unit in Buzuluk. As a member of a machine gun company he fought at Sokolovo, where he was seriously injured. Once he had recovered he took part in further fighting during the liberation of Czechoslovakia, for which he was decorated. In 1946 Levora left the army and became a civilian employee at the Asta Plzeň architecture studio. A year later he entered the Communist Party, though he soon stood down. At this time he began penning a memoir of his time in the Soviet Union. He stopped writing after February 1948 and did not complete the manuscript until 1956. Following a denunciation the StB searched his home, confiscating the manuscript. Levora was accused of spreading defamation and on 24 September 1954 received an 18-month conviction for “sedition” and “defaming an allied state”. He served his term at the Bory and Valdice prisons. He was later a freelance painter (in 1951 he graduated as an art teacher from the Faculty of Pedagogy in Pilsen). In the 1960s he set up and ran an art gallery in Klatovy. He finally published his memoir of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s. Vladimír Levora died in Klatovy on 27 May 1999.

Štěpán Luťanský (1916–1997)

Pečorlag (Pechorlag). Argo, 1999

Imprisoned in 1939–1942: Stryi, Kirovohrad, Arkhangelsk, Naryan-Mar, Pechorlag, Vorkutlag

Štěpán Luťanský was born in the Carpathian Ruthenian village of Volosjanka on 3 August 1916. He studied pedagogy at general school in Uzzhorod and later taught at a general school in Volove. On 11 October 1939 he decided to leave for the USSR, where he was arrested by a border patrol and handed over to the NKVD. He was interrogated at prisons in Stryi and Kirovograd. An aggravating factor was that he had presented himself from the beginning as a member of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, only admitting this was untrue after a number of interrogations. On 20 June 1940 he was sentenced to five years’ hard labour in the Gulag. From Kirovograd Luťanský was sent by train via Poltava, Kharkov and Moscow to a transit camp in Arkchangelsk. From there he and other prisoners were placed on a boat, which carried them over 1,000 kilometres to a transit camp by the Naryan-Mar settlement, where the river Pechora reaches the Barents Sea. From there they sailed on further to the town of Pechora and then by foot to camp colony no. 38, where Luťanský was put to work constructing the Kotlas–Vorkuta railroad. He was later transferred to “colony no. 47, Vorkuta sovkhoz on the river Usa and colony no. 37.” Release came on 17 December 1942, when he and dozens of other Czechoslovak prisoners were placed on a train to the Czechoslovak military unit in Buzuluk. After a grim journey during which one of the Czechoslovaks died Luťanský signed up on 28 January 1943. He fought at Dukla and took part in the liberation of Czechoslovakia. After the war he taught Russian and Serbo-Croat. In 1946 he joined the Ministry of the Interior, working there in the accounts department until his retirement. In the 1950s he wrote a memoir of his years of imprisonment in the Gulag. However, after a visit from a colleague who almost discovered it, he destroyed it. He had a second go at putting down his recollections in the 1960s but again destroyed the text during normalisation out of fear of a search. A final manuscript was created in the 1980s and was finally published two years after the death of its author. Štěpán Luťanský died in Prague on 22 February 1997.

Štěpán Luťanský was born in the Carpathian Ruthenian village of Volosjanka on 3 August 1916. He studied pedagogy at general school in Uzzhorod and later taught at a general school in Volove. On 11 October 1939 he decided to leave for the USSR, where he was arrested by a border patrol and handed over to the NKVD. He was interrogated at prisons in Stryi and Kirovograd. An aggravating factor was that he had presented himself from the beginning as a member of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, only admitting this was untrue after a number of interrogations. On 20 June 1940 he was sentenced to five years’ hard labour in the Gulag. From Kirovograd Luťanský was sent by train via Poltava, Kharkov and Moscow to a transit camp in Arkchangelsk. From there he and other prisoners were placed on a boat, which carried them over 1,000 kilometres to a transit camp by the Naryan-Mar settlement, where the river Pechora reaches the Barents Sea. From there they sailed on further to the town of Pechora and then by foot to camp colony no. 38, where Luťanský was put to work constructing the Kotlas–Vorkuta railroad. He was later transferred to “colony no. 47, Vorkuta sovkhoz on the river Usa and colony no. 37.” Release came on 17 December 1942, when he and dozens of other Czechoslovak prisoners were placed on a train to the Czechoslovak military unit in Buzuluk. After a grim journey during which one of the Czechoslovaks died Luťanský signed up on 28 January 1943. He fought at Dukla and took part in the liberation of Czechoslovakia. After the war he taught Russian and Serbo-Croat. In 1946 he joined the Ministry of the Interior, working there in the accounts department until his retirement. In the 1950s he wrote a memoir of his years of imprisonment in the Gulag. However, after a visit from a colleague who almost discovered it, he destroyed it. He had a second go at putting down his recollections in the 1960s but again destroyed the text during normalisation out of fear of a search. A final manuscript was created in the 1980s and was finally published two years after the death of its author. Štěpán Luťanský died in Prague on 22 February 1997.