THE 20.11.1942 AMNESTY FOR CAPARTHIAN RUTHENIANS, UKRAINIANS, SLOVAKS AND OTHER CZECHOSLOVAK CITIZENS IMPRISONED IN THE USSR

On 20th November 1942 the State Defence Committee of the USSR decided on an additional amnesty for Czechoslovak citizens, primarily from Carpathian Ruthenia imprisoned in the Gulag, and their release to the Czechoslovak Army. This followed intensive efforts from the commander of the Czechoslovak military mission in the Soviet Union, Helidor Píka, and his collaborators, who almost a year previously had succeeded in saving some of the Czechoslovaks in Soviet camps through an amnesty issued by the Soviet leadership on 3 January 1942.

This move opened the gates of the Gulag for the majority of Czechoslovak citizens who in 1939–1941 ended up on Soviet territory as refugees from the Nazi and Hungarian occupations and were unjustly sentenced to slave labour in Gulag camps and prisons throughout the USSR; these already contained dozens of Czechoslovaks sentenced by the Soviet regime for political reasons, such as Vladimír Bláha and Antonín Vodseďálek.

Since 2008 the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes has been conducting interviews with refugees from Carpathian Ruthenia imprisoned in the Gulag. It has also been documenting places associated with their hardship in the USSR and, in cooperation with the Ukrainian state and security archives and the University of West Bohemia in Pilsen, it has digitalised the archival collection of the State Archive of the Zakarpattia Oblast, which, as with other NKVD/KGB documents, it is gradually expertly processing and making accessible to the public.

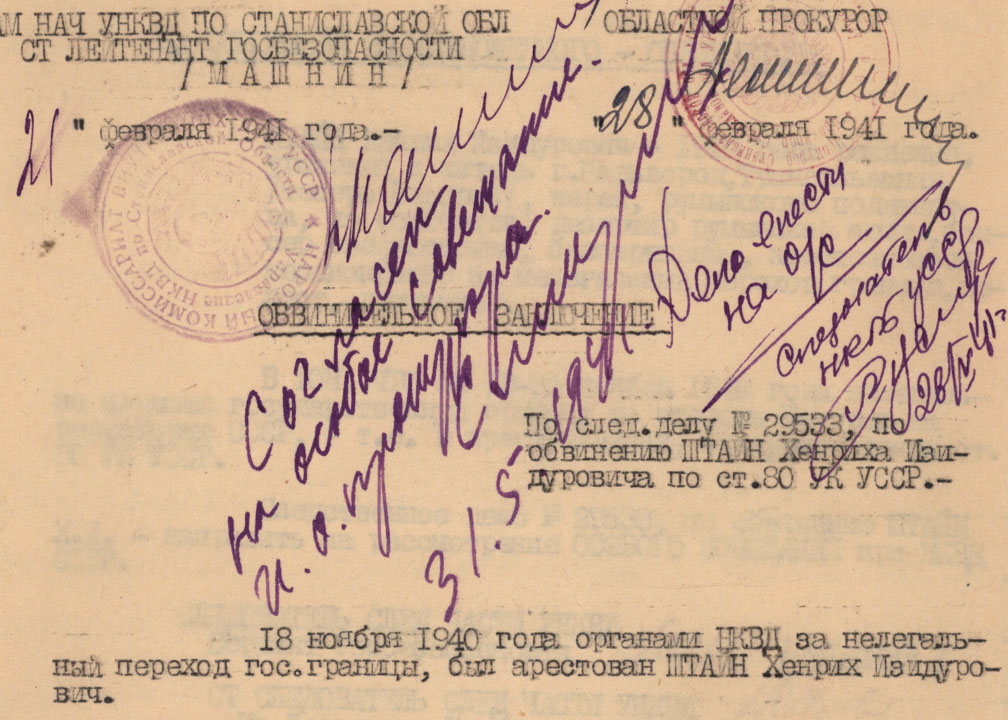

On the occasion of the 80th anniversary of the amnesty, the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes is publishing another thousand NKVD investigative files on refugees from Carpathian Ruthenia, which it acquired from the Ukrainian archives.

Since the beginning of the project, an essential element of the research has been cooperation with survivors in the Czech Republic and Ukraine, whose testimonies have regularly been published, as well as with the relatives of victims of Soviet repression. Project staff have provided them with personal files they have obtained, including information on the fates of their ex-prisoner family members and friends, in particular those who did not survive the hardships of the Gulag. Family archives are for their part a valuable source for historians in studying the life stories of individuals prior to imprisonment and in some cases after release and return to Czechoslovakia. This cooperation is captured in a published photo gallery from interview recordings, meetings with relatives, handovers of NKVD documents and acquisition of photos from family archives as well as short biographies that have been published.

This wide spectrum of sources is subsequently used by project staff in the preparation of expert and popularising materials and the building of a database of victims of Soviet repression among Czech and Czechoslovak citizens.

As is laid out in detail in a page dedicated to the amnesty of 3.1.1942 and attached links, during WWII the inhabitants of Carpathian Ruthenia accounted for the largest number of the roughly 8,000 Gulag prisoners from Czechoslovakia (around 5,500). Paradoxically, however, they were the last to be released. Moscow initially did not want to allow inhabitants of Carpathian Ruthenia to fight for Czechoslovakia. It also had doubts about their reliability in terms of political outlook, which is summed up in a dispatch to London from Píka: The spirit of the officers from Carpathian Ruthenia is clearly Czechoslovak. After painful experiences at labour and internment camps and prisons, their firm target is freedom in Czechoslovakia and they will be opposed to any amalgamation of Carpathian Ruthenia into the Soviet Union. The unwillingness of the Soviet authorities to release Czechoslovak citizens from Carpathian Ruthenia into the Czechoslovak Army was linked to the planned annexation, as Píka registered and reported to London: The special interest of the Soviet organs of the NKVD in questions of nationality of Carpathian Ruthenes not being raised in the unit, the article by ambassador Fierlinger in Our Army in the USSR – all of this creates a vague sense that in the question of Carpathian Ruthenia there are certain tendencies, or plans, as yet unspecified, perhaps ultimately claims, for the incorporation of Carpathian Ruthenia into Soviet Ukraine. The focus of the prescient words of the subsequently executed Píka is also the subject of the specialist pieces The End of Czechoslovak Carpathian Ruthenia by J. Plachý and The Command of Liberated Territories in Documents, 1944–1945 by Z. Vališ, published by the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes.