THE 1942 AMNESTY FOR CZECHOSLOVAK CITIZENS IN THE USSR

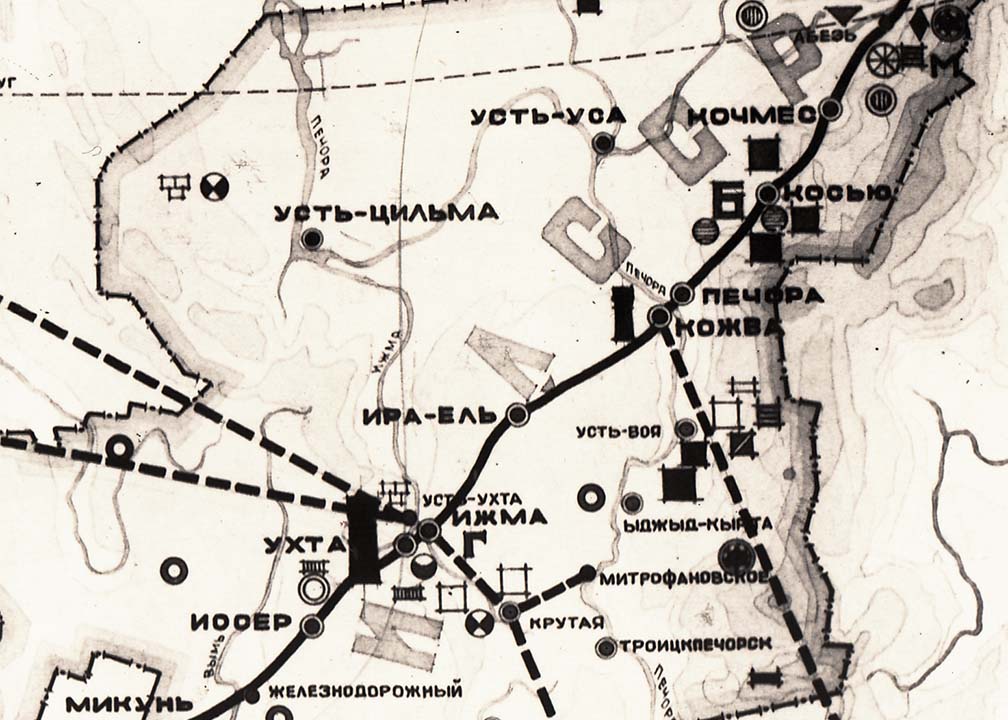

On the occasion of the 80th anniversary of the declaration of a Soviet amnesty on 3 January 1942 pertaining to Czechoslovak citizens imprisoned and interned in the USSR, the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes (ÚSTR) will publish a collection of NKVD investigative files in cooperation with the Department of Cybernetics at the University of West Bohemia in Pilsen. These files were kept on 1,000 Czechoslovaks out of a total of approximately 8,000 who were imprisoned in Gulag camps during WWII. This represents the first collection of Soviet secret service files obtained within the framework of systematic digitalisation at the State Archive of the Zakarpatska Oblast (DAZO) in Uzzhorod. Archival fond no. 2,558 contains NKVD files on approximately 5,500 persons who in 1939–1941 fled the Nazis and the Hungarian occupation to the Soviet Union, where they were sentenced to three or more years in labour camps.

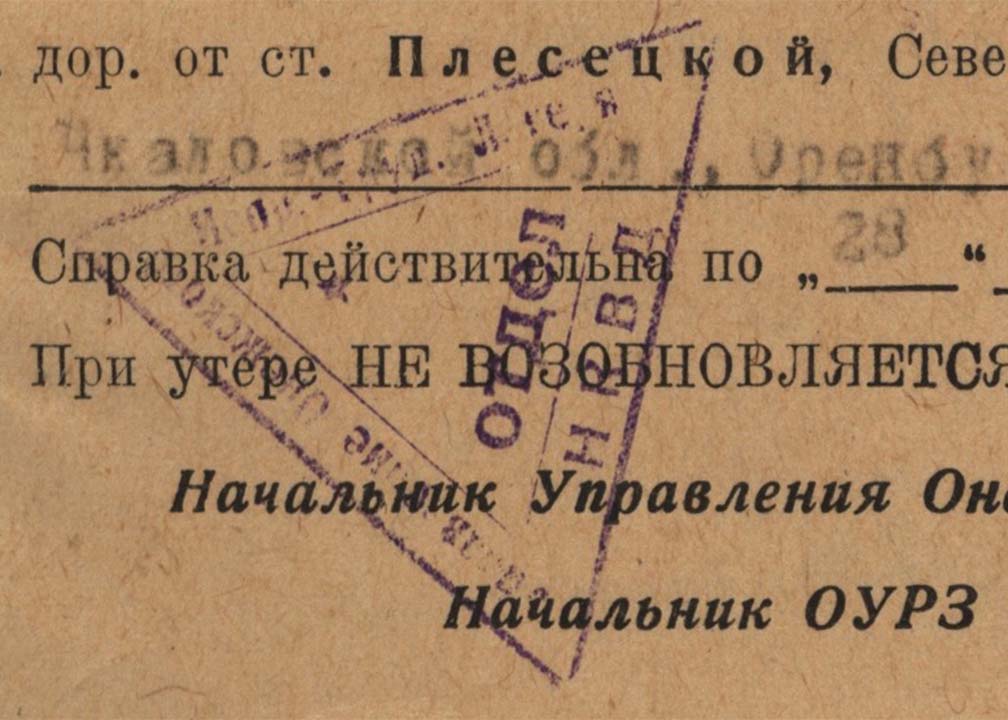

The published investigative files on both individuals and whole groups include, among other things, arrest reports, fingerprints, photographs, personal inspection reports, detainees’ questionnaires, reports on the suspects’ frequently repeated interrogations, charges, verdicts, reports on place of punishment, release documents and Gulag death certificates, as well as rehabilitation judgments. Detainees’ personal photographs and documents confiscated by the NKVD are a valuable element of these files.

ÚSTR will simultaneously also publish files, photographs, interviews and other accompanying texts on this subject gathered within the project Czechoslovaks in the Gulag.

The amnesty for imprisoned Czechoslovak prisoners was successfully agreed at the start of 1942, when on 3 January 1942 the USSR’s State Defence Committee decided to create Czechoslovak brigades on the territory of the Soviet Union. This resolution also included a decision on the early release of imprisoned Czechoslovak citizens, with the exception of “persons suspected of espionage against the USSR.” The Soviet leadership was mainly forced into reevaluating its treatment of Gulag prisoners by Nazi Germany’s June 1941 attack on the USSR. A key role in the negotiations was played by the commander of the Czechoslovak military mission in the USSR, Colonel Heliodor Píka, who the Communists executed after the war. His efforts to save jailed Czechoslovaks and the subject of the amnesty have been outlined by Military History Institute historian Zdeněk Vališ in, for instance, the article From the Soviet Gulag to the Czechoslovak Army: Helidor Píka in the fight for the lives of Carpathian Ruthenians.

The cruel fates of Píka’s main collaborators and their efforts to save compatriots from Carpathian Ruthenia, whose release they finally secured at the end of November 1942, have been described by Jan Dvořák, Jaroslav Formánek and Adam Hradilek in two chapters of the book trilogy Czechoslovaks in the Gulag: Return my Czechoslovak passport and From patriots, traitors. Selected life stories of those amnestied have been published by J. Dvořák, A. Hradilek and Z. Vališ under the title From Gulag camps to the Czechoslovak military unit in the USSR. Also among the first documents that Czech historians obtained from DAZO was a file on the notorious Communist prosecutor Karel Vaš, published in 2012: Karel Vaš in the USSR: Prisoner and NKVD collaborator.

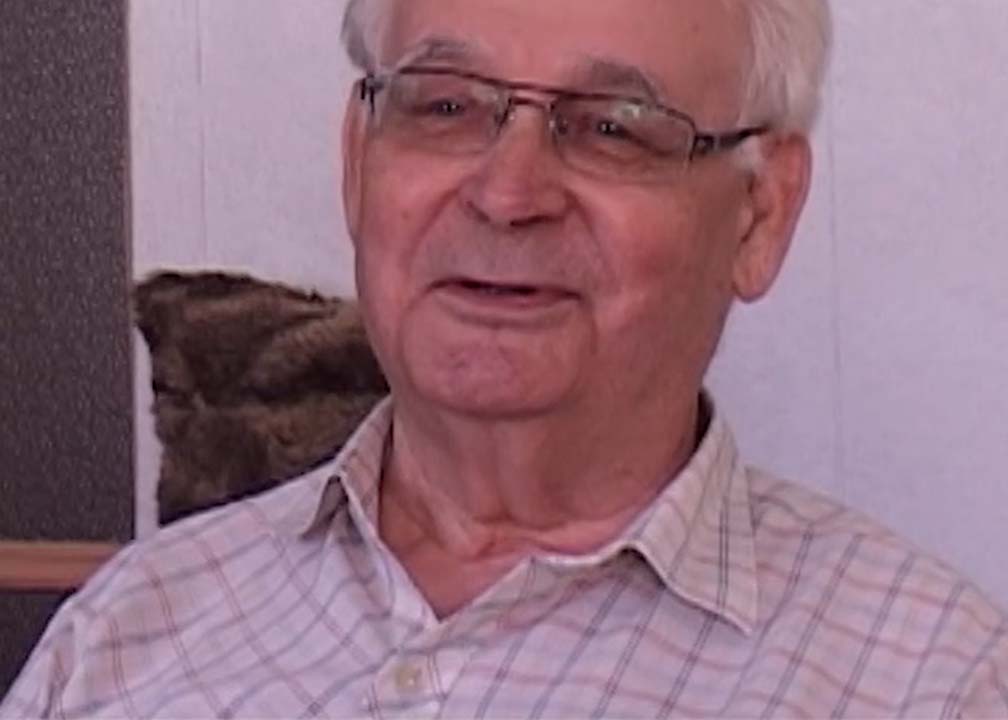

ÚSTR’s efforts to acquire Soviet security forces documents were preceded by attempts to search out and record life stories of Czechs imprisoned in the USSR; this resulted in a series of dozens of interviews recorded in 2008–2015, some of which can be found here.

The stories of some, including Jan Plovajko and Václav Djačuk, have been presented to the public in the form of a story map on the website of the Gulag.online virtual museum, a joint project of ÚSTR and the Gulag.cz association.

Historians have also succeeded in tracking down and interviewing relatives of prisoners or those who died during their sentences, obtaining documents, photographs and handwritten memoirs from family archives. Excerpts from memoirs of this type by Jan Bačkovský were published in the Czech-Russian anthology Echoes of the Gulag; other materials gathered have appeared in the book trilogy Czechoslovaks in the Gulag, a documentary film of the same title by director Marta Nováková, themed exhibitions and other outputs.

Several thousand people, predominantly refugees from pre-war Czechoslovakia, had been released under the amnesty by the end of 1944. Among the Czech prisoners let go were the future anti-communist resistance fighter Pravomil Raichl and painter Vladimír Levora; the latter was convicted in the 1950s for bringing out a memoir of the Gulag, which ÚSTR helped publish in 2020. The amnesty most concerned (several thousand) Carpathian Ruthenians and several hundred Czechoslovaks of Jewish origin, whose stories were explored by J. Dvořák and A. Hradilek in the publication Jews in the Gulag: WWII Soviet labour and POW camps in the recollections of Jewish refugees from Czechoslovakia.

However, for approximately 15 percent of the Czechoslovaks the amnesty came too late and they died in labour camps in atrocious conditions. These included Israel Abrahamovič and Ondřej Grossmann. Other “dangerous criminals” and “spies” could only dream of being pardoned, or were released only to soon be rearrested by the NKVD and end up back in the Gulag for many years. Among such cases were those of Karel Goliath and František Polák, whose selected memoirs were published as Seven Years in the Gulag by ÚSTR in 2017. NKVD documents also show that release was not granted to a great many refugees with disputed nationality, low sentences or specialised skills in various fields that camp commanders were unwilling to relinquish. In some cases prisoners did not hear about the amnesty and only returned to their homeland having served out long sentences, such as Ernst Beiner. Others, such as Egon Morgenstern and Kurt Rosenzweig, did not return home after completing their sentences, remaining in the USSR.

The opportunity to enter nascent foreign military units in the Soviet Union gave freed prisoners hope of salvation. However, the journey from camps scattered throughout the USSR to the Czechoslovak unit in Buzuluk took a number of weeks. Some of those amnestied died in transit from the camps, such as Michal Jackanič, or arrived sick, undernourished and physically exhausted. For that reason some, like Robert Sylten, were not able for recruitment and training and required months of convalescence, or died shortly after arrival.

Most of the released volunteers took part in fighting on the Eastern Front, where many died at Sokolovo (see Michal Vološin), at the Dukla Pass (see Ivan Hladinec) or on other bloody battlefields or at the hands of the Nazis (see Karel Egger).

Systematic digitalization at DAZO and other state oblast archives in Ukraine follows on from similar efforts at ÚSTR and at the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) archives; see documentation on the trial of the Czech teachers. Digitalisation was launched on the basis of an agreement signed with the State Archival Service of Ukraine in 2020. This deal followed years of research at the archive and efforts to digitalise the whole collection, which was mainly supported by the Czech Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Embassy in Kiev and direct negotiations with the director of DAZO, M. Misyuk, in June 2019 and a delegation from the Senate of the Czech Parliament headed by its deputy speaker J. Horník and the ambassador to Ukraine, R. Matula. The acquisition, processing and publication of the documents would not be possible without the financial support of the Czech Ministry of Culture and a grant it provided to ÚSTR in cooperation with the University of West Bohemia in Pilsen for the project The Digital Archive of NKVD-KGB Documents With Regard to Czechoslovak History.

The complete digitalization of these documents will conclude next year, shedding light on the stories of thousands of unknown victims of Soviet repression and outlining the latest findings on the number of Czechoslovaks interned in the Gulag, their placement in individual camps, death rate and fates after release.

A large number of digitalized files are gradually being processed using software developed by a team at the Department of Cybernetics at the University of West Bohemia in Pilsen. The software first converts scanned documents, using OCR methods, into electronic text. It then enters them into a specially designed database which allows for interactive searches for words or short phrases using a graphical user interface. The database will be fully functional by the end of 2022.